[ad_1]

Whenever I search for toothpaste at the grocery store, I am reminded of browsing the projects on Bjarke Ingels Group’s (BIG) website. Each bright and sparkly box looks unique to fit a variety of specific needs: fresh breath, tartar control, sensitivity, whitening, etc. But upon further examination of each tube, they all claim to do what the other tubes do anyway. So if the whitening toothpaste also includes tartar control, sensitivity, and fresh breath, but the sensitivity toothpaste includes whitening, fresh breath, and tartar control, which one am I to choose? Does one toothpaste actually do any of these things better than the other? How can it accomplish one thing if it is so busy doing everything else? Faced with these vexing questions, most people buy whatever is on sale.

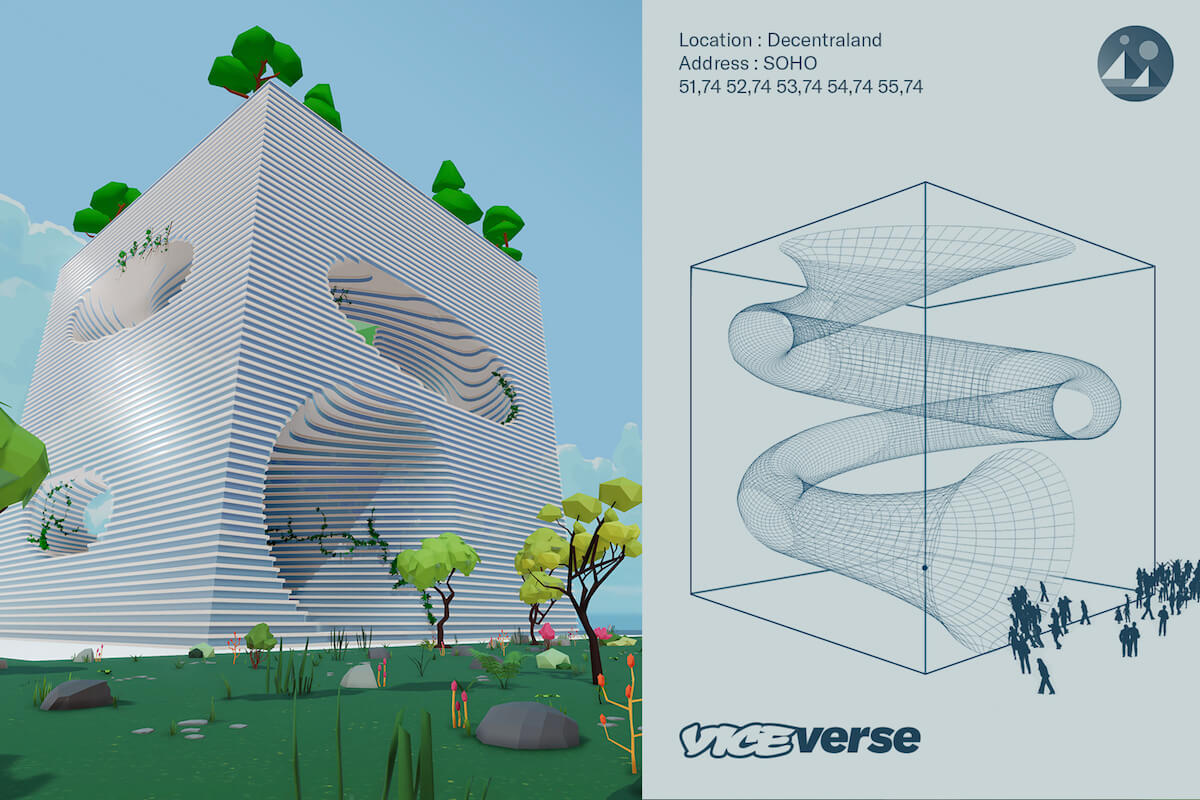

It seems like BIG had an unbuilt competition project called TEK sitting on the shelf, collecting dust, so it went and found a buyer in VICE Media, a digital media and broadcasting company headquartered in Brooklyn, New York. But here’s the kicker: the building isn’t in Brooklyn. It isn’t even in the United States, but has space enough for the entire VICE payroll which includes offices in Mexico City, London, and Singapore. It is in a unique site where the weather is always perfect, handrails are no longer necessary, and the ramps don’t have to be ADA-compliant: It is located at 51,74 in the Decentraland metaverse.

Decentraland is a browser-based game world where anyone anywhere on Earth with an internet connection can create an avatar and meet, talk, and hang out together. I visited and described the world itself once before, and despite the sour taste in my mouth from a bland and explicitly non-revolutionary visit, I begrudgingly invited my Twitch followers to join me once again in exploring metaverse architecture:

Right away Decentraland hit me with a cacophony of failures. My browser crashed continuously time and again before I could even reach the plot of digital property (LAND) where the VICE headquarters supposedly stood. The free and accessible servers were busy, something I am willing to deal with in order for this kind of tech to be truly available to all. I happily reconnected, reloaded, and finally emerged onto the parkfront property face-to-face with a glistening white cube inscribed with an inviting yet mystifying wormhole shape.

I’ve never been to a building picked from the clearance section before, but this was surely that experience. The headquarters is situated on an expensive piece of LAND on the northwest corner of a public park called Soho Plaza. The rooms inside of VICEVERSE, the witty nickname of the project, are filled with common office tropes including a ping pong table, a meeting space, a selection of suspiciously saturated ficuses, and a sloping green roof to top it all off. The form is outfitted with opaque blue glass-like material and bright white horizontal louver structures, as if there was a need to shade the sun on the interior (there isn’t). The irony of having a green roof on a metaverse building is the most paradigmatic example of the failures of this project. Why even bother having an inhabitable rooftop space when the build distances (how far you can “see” in the game) are limited anyway. Plus, the sun can set whenever I want, and do I actually need to mention how a green roof is mechanically not necessary in a simulated ecology?

The feeling of a feigned concern for global sustainability resonated through the project. An exterior louver system isn’t necessary because the sun doesn’t shine through the glass material, and even if it did, you don’t have to heat or cool the interior space. The ivy growing all over the building doesn’t sequester carbon or emit oxygen. VICEVERSE even includes a hyperlink which took me to the website of a simulated store located on the Great Pacific Garbage Patch where I was badgered to bid on shoes in order to raise advocacy money; environmental consciousness is the logical veil of choice for eco-fashion grift.

I’m especially disappointed because environmentally reactive elements can be quite provocative aspects of architecture in digital space, but they usually exist as storytelling in concert with a simulated ecology. How does perfect weather in a purported libertarian capitalist techno-utopia make sense as the environment for a constant barrage of climate anxiety–induced greenwashed virtue signaling? If everything is all good, how come it’s not? Something doesn’t add up. To be fair, the sustainability question is a criticism which can be made about just about anything. We are all using power, and I am typing this review on a desktop PC running an unnecessarily girthy graphics card. But to think my complaints are about energy itself misses the point: The architecture is straightforwardly bad.

I anticipated that visiting a metaverse project designed by a very good architect would cause some kind of visible, tangible differentiation between it and the surrounding built environment. But when examined closely, the formal effect and legible simplicity we have come to idolize about BIG’s work seems wasted in this context. Its sweeping horizontal curves stop uncomfortably in the threshold of each connecting room. The volumetric space between the curved circulation and square corners is unfortunately visible and sadly without a floor. The circulation narrows so much around the edges that my avatar nearly falls to its death just going from one level to another. What is missing to me is the value in what has been purchased. Attention to detail, a building that responds to context, a provocative sentiment for a new way of living, none of these services have apparently been rendered. It’s all fun and games until you try and measure it up with the fact that Decentraland dares us to “determine the future of the virtual world.” What exists instead is a clunky and poorly executed version of a delightful 13-year-old competition entry. I hope they got it on sale.

[ad_2]

Source link