[ad_1]

Are our city’s markets as important as a national theatre or a public square?

Alexis Şanal.

Alexis Şanal, the Istanbul-based architect who came to Australia as part of the Droga Architect in Residence program in 2018 thinks so and she’s prepared to make the case. She also thinks that other public spaces and buildings could be improved by taking some lessons from the way markets use space.

Raised in Los Angeles, Şanal co-founded the architecture and design practice Şanalarc with Murat Şanal in 2002. Her proposal for the Droga residency was to build on her past research into Istanbul’s open-air neighbourhood markets and investigate ideas about public marketplaces in an economically advanced nation such as Australia.

Continuing our look back at the Droga program, we spoke to Şanal about what makes the Australian market unique, genuine bottom-up community involvement in design and the importance of “play” in generating ideas.

Josh Harris: I thought we’d start from the beginning. How did you hear about the Droga program and what was the impetus for applying?

Alexis Şanal: In undergraduate school, in 1995, I was an exchange student at RMIT. And then in 2007 I came down to the University of Queensland as a guest lecturer. Therefore, I’d started a long relationship with Australia. When the program started many colleagues and friends brought it to my attention and, fortunately, I got around to applying after a few rounds.

JH: Could you give me an impression of what you were doing day-to-day when you arrived in Australia, beginning the residency? I gather you were you were very busy.

AŞ: I had never lived in Sydney nor visited for a long time. So my first two or three weeks was really about walking the city – sea to valley, bridge to park. I’m an early riser so my first few weeks I was waking up very early and walking, walking and walking, taking in the rhythm of the city, the time-based intelligence of the city. I was mining online information on markets and where they were located and mapping them. And one of my criteria for the selection of markets that I looked at is that I had to be able to get there easily by public transportation or walk there within 20 minutes from downtown Sydney. It was a combination of meandering and going around with great intention and eating a lot of really good food.

JH: You mentioned markets, which were a key focus of your research. You’ve said that markets are ubiquitous among all civilizations, but I was wondering what interested you specifically about Australian markets.

A study of King’s Cross Market, Sydney.

AŞ: I had been studying the markets in Anatolia and especially in Istanbul, which are well over a thousand if not two thousand years old – they are a very enduring practice. But in the contemporary sense, we have a very developing economy. I thought to really challenge the research that I was doing here on markets’ social, civic and economic relevance, that it would be really interesting to contrast that with the other extreme, which is an incredibly new settlement, or city settlement, and a very advanced economy. Do new cities and very new economies with very healthy and robust economies value these civic markets? I make the argument that they are a civic space, these daily markets.

JH: In your lectures you referenced Bruce Pascoe, whose work I guess speaks to the contradiction of Australia, that it’s the one of the newest countries in terms of Western colonization, but also among the oldest civilizations in the world. How did Bruce Pascoe’s research into Indigenous agriculture inform your own research?

AŞ: We value markets as civic space, we value them up there with cultural spaces. And one of the things I found really interesting in Bruce Pascoe’s work [making native grains available commercially] was that he really highlights that they’re commercial spaces actually, and they’re experimentally commercial spaces, and they’re spaces that are quite interactive, where ancient and new [can come together]. It is a place where we are iterating our experiments with the mundane parts of pluralism and diversity. So that’s how I referred to his work, in that he also found markets valuable [as ways of] introducing aspects of this very ancient culture, ancient way of food production, ancient way of farming to a very new setting. That was his kind of proposition.

JH: What were some of the markets you visited in Sydney?

AŞ: I visited everything that I could. Street markets, community markets, farmers’ markets, clothing markets, craft markets, but mostly within what’s considered central Sydney.

JH: And you also managed to visit markets in other cities. I saw you visited Adelaide Central Market.

AŞ: Yes. One of the interesting things about Australia is that the major cities were built pre-modernism and that really hit me hard because as an American from the west coast very few of our cities were built pre-modernism.

Central markets are still present in those cities and are having a huge rebirth, but in Adelaide, which never tried to rethink its civic infrastructure downtown so much, its market continued and didn’t try to be reinvented and therefore has this longevity, which made me realize that modernist planning took the marketplace and said it’s not actually a civic space. I make an argument that it’s in fact a civic structure as important as the national theatre, as important as other public buildings. And by modernism reducing it, we lost this kind of iterative public theatre. And hence why we’re seeing the rebirth of them in kind of a new way – the end of modernism as a kind of meaningful way to build cities.

JH: You also place a lot of emphasis on the spontaneous, do-it-yourself modes of placemaking and the way they can influence formal architecture. Could you explain how that works, how markets fit into that paradigm?

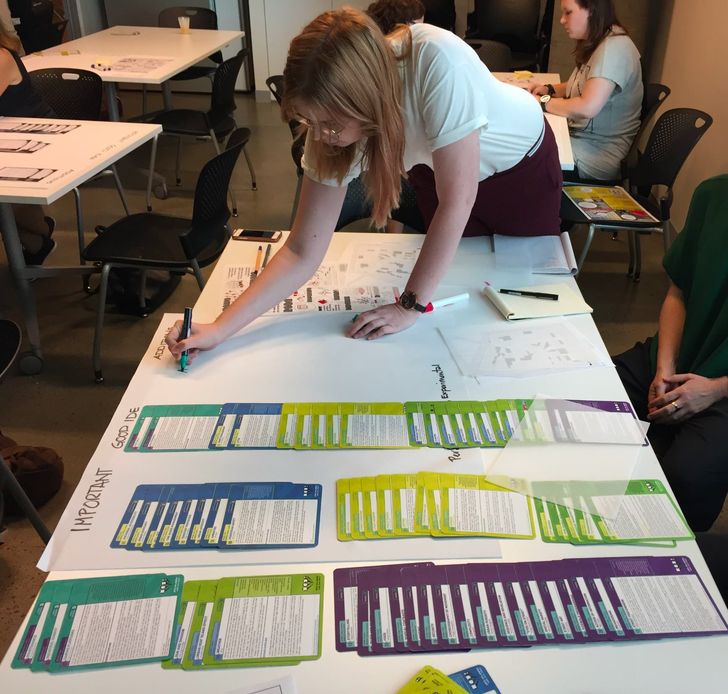

A workshop using the Imaginable Guidelines cards.

AŞ: If you look at any cultural institution – and this pandemic is only amplifying this – the overhead to run dedicated space is just overwhelming. It’s incredibly expensive to run dedicated spaces. And yet the city is filled with so much residual space, and space that can be really activated. If we really think of the city and the way that one-day markets operate, [we] have all of this land potential or resource potential of place and space and people within walking distance and we can much, much, more intelligently use these resources. I was finding this happening in Australia. Cultural actors and institutions and organizations are reappropriating leftover spaces in quite meaningful and interesting ways. And markets have been the pioneers to show us that time-based uses of place can make civic form.

JH: Could you give me a specific example? I saw you presented on the Flowstate performance space in Brisbane.

AŞ: This one is using a fixed space a little bit more than some of the others, they have appropriated an old food and beverage space in a park. They hold rehearsals there at a certain time, they come out and do performances at a certain point, but the rest of time this place is part of the park. Instead of having a dedicated performing arts space, which is very costly for these fragile organizations to operate, it’s reinventing already available infrastructure.

And then then in Melbourne, I found this small organization, Play On, which is trying to introduce high classical music to teenagers and young adults and trying to reinvent the venue. Again, to go see classical music is so overwhelmingly expensive, to maintain the Sydney Opera House is so overwhelmingly expensive that if you take that expense out, you can make accessing really high-quality content affordable.

They looked for places in the city that are underutilized [such as] an underground parking lot in a housing estate. And they created a protocol where for two months in a year they can do their programming in it. Then because of that, they can also explore new ideas of cultural production.

JH: Could you explain the design game you were developing while you were in Australia, Imaginable Guidelines?

AŞ: This was our practice’s response to a lot of the things that we found were happening in Turkey, where people feel very excluded from discussions of public space and discussions of agency.

And so this was our response to say, look, there’s these amazing minds throughout the city that know about how to build great public space [but] everybody’s so fragmented. If you really want to participate, why don’t you put your knowledge out there, not your opinion. What is your knowledge that you can contribute to making better public space? Whether it’s water management, whether it’s more phenomenological if you’re a sociologist, whether it’s economic ideas if you’re an NGO, if it’s universal accessibility – the city is actually more complicated than it looks.

My big vision always has been to have cities around the world crowdsource their city design guidelines so that you’re directly using a bottom-up process rather than a community consultancy process, which I don’t find very satisfying and ends up with a lot of jargon and ambiguous consensus building. Instead, just say, look, “what is a kerb to you?” And if we all agree that that’s a kerb, then that’s gonna be our kerb. And the kerb for the Australians will be different than the kerb for the Turks, will be different for the kerbs for the Danes. These things are a cultural phenomenon as well.

JH: So how does Imaginable Guidelines differ to the standard community consultation process?

AŞ: At least in our experience, both in developed economies and in [developing] economies, every urban design problem is unique and needs a unique design guideline. So, [with Imaginable Guidelines] you can actually customize the guideline through negotiating with cards. And what we found to be the most effective part of it was [the idea of] public play. Role playing makes people imagine things better. If you have agency through an object rather than just your will, you get people that are not used to talking, talking and people that talk too much, they can’t talk without a card or something to contribute. It makes this negotiation much more kind and much more fun. I have no idea how it works, but by playing the game, you get this really in-depth learning happening.

And I guess my real dream is – I actually think that most designers are quite competent, and if they were given a good design brief, then they would do more meaningful designs for the citizens and skip some of that rough process where the design brief was bad, therefore, the design is bad and the city blames the designer and the designer says “I was just told what to do.” [So the idea is to] get rid of this bitterness that so much consultancy has engendered in the community.

JH: To go back to Drogo, I guess a goal of that program was to share knowledge. Could you speak a little bit about your interactions with people you had here, what you learned from others, what you were able to teach them.

AŞ: I was very fortunate in that I had a community of people there who were really very generous to introduce me to a lot of people. I got to engage with the City of Sydney through Eva Rodriguez who I knew from doing the Laneways Project, and I worked a lot with Lisa Corsi on Imaginable Guidelines and how we could use that for public art practice and these more temporal uses of public space. I got to meet Kirstin Seale, who was an academic studying markets over at UNSW.

But then I also, through the workshops, got to meet people like Tobhiyah [Stone Feller] who introduced me to what was happening at Flowstate. And then by having these social structures, people would say things like, “you have to meet Philip Thalis,” and he brought me so much insight into public Sydney, which was great because I had already gotten to know Sydney and I had already framed a lot of my thinking. He pushed me by thinking five steps further, especially on this idea of civic form and enduring civic form and the politicization and privatization of public space.

Şişhane Park by Şanalarc.

Image:

Olivve Wimmer

JH: It sounds as though it was a very transdisciplinary sort of exchange; you weren’t just talking to architects.

AŞ: That’s really the goal, to get all of us architects to be better listeners. Because I think we are really good designers. And when we have a really good design brief, we make good work.

JH: Would you say the experience in the Droga program has had an impact on the work that you’ve been doing since 2000?

AŞ: Absolutely. I mean, hugely. If it wasn’t for the fact that our economy here has been a train wreck and that I have small children, I would be doing a lot more sharing of how much I learned. It’s still very much on my radar. I’m planning to publish a book on the research and to start putting this research much more into conferences and other things. It has had a huge impact on my own practice. This year’s my first year teaching again [since the program] and we set up a research unit looking at markets. And then the pandemic happened. I’m certainly pushing along a lot of this.

JH: Are the markets open as usual in Istanbul right now?

AŞ: They are. They’re considered essential. Social distancing, everything. It’s fantastic, you have rules, you have to get your hands sanitized, you have to wear back a mask, they’re all a certain distance apart. They’re really good at self-organizing.

JH: Lastly, how did you like living in the Droga apartment [designed by Durbach Block Jaggers] while you were in Sydney?

AŞ: Yes, of course it’s fantastic. But I’d like to say something more on the Droga program and Daniel and Lyndell Droga. It was just really exciting for me to see that there was this, not just philanthropy, but this type of soft infrastructure. That soft infrastructure should be led through institutions and universities and patronage. So that was a really rewarding, touching experience, that level of cooperation was very exciting to me.

And being in that residence, both being very beautiful but also being very central, was very exciting. You have the Salvation Army [emergency accommodation] next door, so there’s this sense of seeing living Sydney. I didn’t feel isolated; I felt in the bowels of the city.

[ad_2]

Source link