[ad_1]

On September 18, Hurricane Fiona, a category 1 storm, struck the southern part of the island of Puerto Rico. All residents of our Caribbean commonwealth were without power, 75 percent without running water, and many suffered from historic flooding. The storm is estimated to have caused over $2 billion in damage and the deaths of at least 21 people.

Fiona won’t be the last climactic event that strikes our territory. My generation, growing up in Puerto Rico during the 1980s, learned to deal with the unpredictable wrath of nature. After Hurricane Hugo battered the northeast in 1989, Puerto Ricans became well-versed in hurricane preparedness. Despite multiple subsequent storms, nothing prepared us for the aftermath of Hurricane Maria in 2017. We are still healing the emotional wounds from that category 4 hurricane, which impacted the entire island. It left a major gash in the island’s economy and infrastructure and accelerated the depopulation of the island: The 2020 U.S. Census listed Puerto Rico’s population as 3.3 million, down from an all-time high of 3.8 million in 2000.

Based on our previous experiences, Hurricane Fiona shouldn’t have deprived citizens of essential services like electricity and running water. Schooled by the trauma of Maria and a series of earthquakes in 2020, we were expecting the worse. Still, the government refused to acknowledge that what remains of the island’s infrastructure didn’t fare well in this latest deluge.

During the early-to-mid 20th century, Puerto Rico was a laboratory of ideas about economic development for the U.S. The island quickly developed into what the U.S. touted as a model for economic development for Latin America. The idea of achieving middle-class status was suddenly viable for Puerto Ricans. Neighborhoods sprouted, and the government brought electricity, running water, and telecommunications to the most rural areas of the island. But the pace of development left critical vulnerabilities unchecked. Poor land-use regulations and a lack of oversight from regulatory agencies have plagued the island, allowing communities to develop in flood-prone areas with poorly planned infrastructure.

Now, well into the 21st century, Earth’s temperature is on the rise, which results in intensified natural disasters like hurricanes. Neither the maintenance nor the planning of utilities on the island will survive much longer in their current state. Government mismanagement forced the island to declare bankruptcy in 2016. As one of the consequences of debt restructuring, the government privatized the power grid distribution and enabled LUMA Energy, a foreign private consortium, to manage it. Privatization has not alleviated the issues; instead, the move has become a scapegoat for the government to blame someone else for the unreliable power grid.

Last April, an island-wide power blackout occurred on a typical Wednesday evening. Unfazed, Puerto Ricans scrapped their plans, made it home, pulled out their generators, checked on their water reserves, and dusted off flashlights and portable radios to pass the time. The power grid is so vulnerable that our stoicism has become resignation. “This too shall pass,” we told ourselves once more. By the time Fiona became a hurricane warning, it was not a matter of whether the power grid would fail but rather when it would happen and how long it would take to recover.

While the storm caused major flooding in the mountainous and southern regions of the island, areas in the northeast were left relatively unscathed. We are not only resilient but resourceful and empathetic. While under an island-wide power blackout, many Puerto Ricans mobilized to help their fellow neighbors by clearing roads, bringing supplies and food, rescuing others from flood conditions, and offering emotional solidarity.

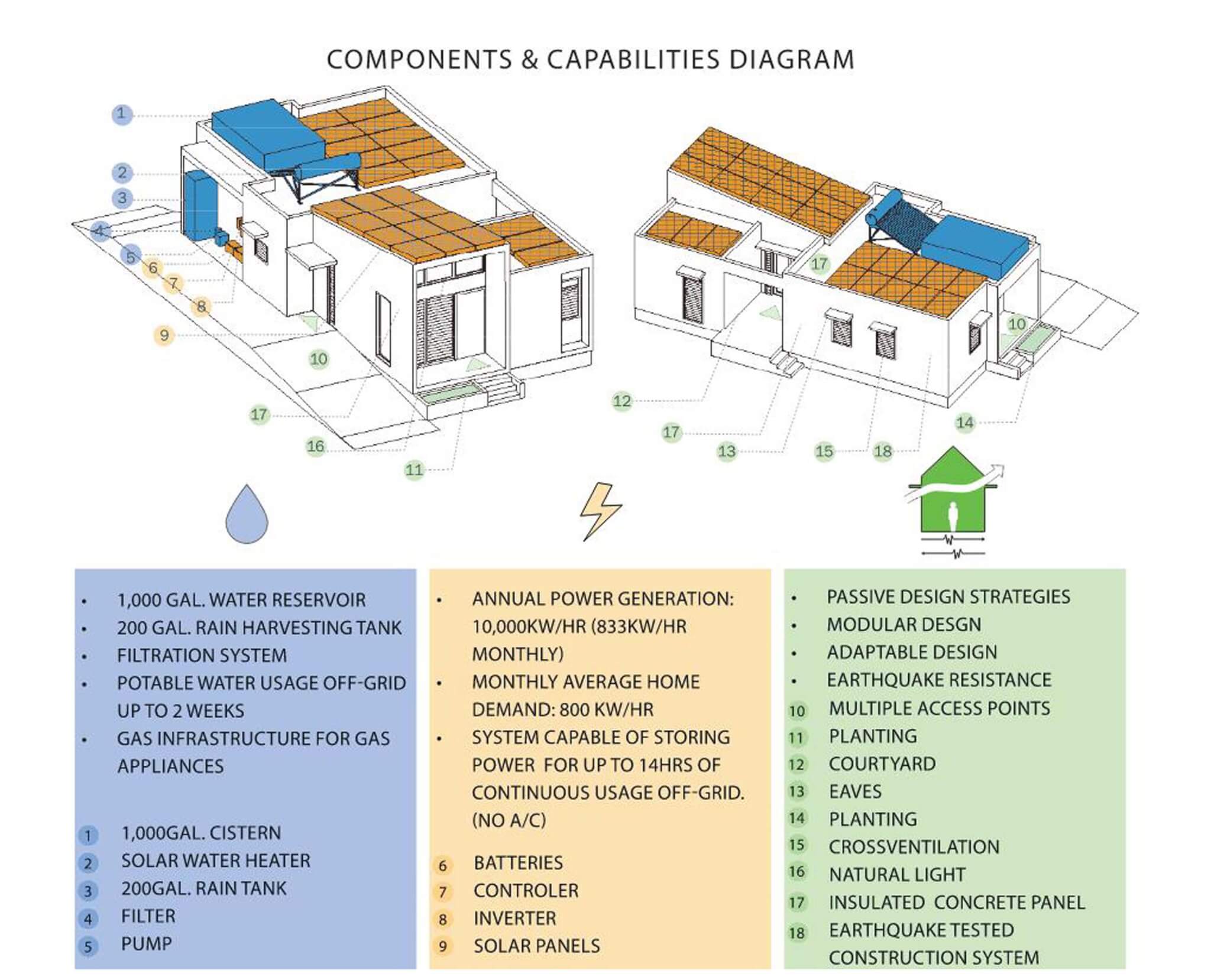

My colleagues at Marvel have been actively participating in these efforts. Volunteering since day one, they have carried out tasks like inspecting damaged property and bringing food and supplies to many places in the south. There was no expectation that the central government would react with any sense of urgency. Currently, organizations like Taller Salud, Casa Pueblo, La Maraña, and Resilient Power Puerto Rico are significant groups that support communities and empower citizens. Marvel is also working toward various prototypes of resilient homes, which harvest energy from the sun, store water, and mitigate water runoff with rain gardens.

A few weeks after Fiona, Hurricane Ian struck Florida’s Gulf Coast. Utilities were mostly restored to areas with minimal impact, enabling citizens and the government to focus on the critical impact zones. Back on my island, I wonder how many more of us could help those in dire need if we did not have to worry about the stability of the utilities at home, which fulfill our basic needs.

For Puerto Rico, and the rest of the U.S., major questions about energy sourcing lie ahead. According to the Energy Information Administration (EIA), fossil fuels provide 97 percent of the island’s power; we must work toward a future in which the sun powers our homes and businesses.

Resiliency is defined as the capacity to “recover quickly from difficulties” and to “spring back into shape.” How long can Puerto Ricans—full U.S. citizens—be expected to endure and bounce back from adversity? We are exhausted from being resilient. The challenges we have experienced prepared us to lead the way in finding solutions to global issues. Strategies must come from community-led organizations and committed individuals who don’t yield to traditional power structures.

Now, as designers from an island that has limiting geography but is rich in resources, we need to chart a future in which design and planning shapes policy and unlocks the strategic investment that allow our island to become a true laboratory of ideas to address climate change.

Annya Ramírez-Jiménez is a director at Marvel. She practices architecture with a focus on projects that promote more equitable cities.

[ad_2]

Source link