Sunday is one of several small terraces arranged amid an assortment of houses, repurposed factories and a pub in a typical Fitzroy backstreet. This area lays claim to the earliest terrace housing in Melbourne, with examples from the 1850s still standing in nearby streets. In the book Fitzroy: Melbourne’s First Suburb (1989), professor Miles Lewis suggests that these rows of similar houses are not an inevitable solution to inner-city density but rather a social construct. Professor Lewis draws parallels to London examples where speculative builders jammed together compact versions of an idealized “gentleman’s residence,” maintaining stereotypical arrangements and quantities of rooms but miniaturizing scale to suit site and budget.

The owners of Sunday had lived in the house for some time, holding its unsteady surfaces together with enthusiasm and cheerful yellow paint. With no desire to ever move, their admirable objective was to make it better, not bigger. Befitting their literary occupations, the clients prepared a highly articulate brief for Architecture Architecture, describing the atmospheres and behaviours they desired instead of the usual shopping list of new facilities. One of the clients grew up in a house designed by Paul Couch in Mount Macedon, and this memorable environment had an enduring impact: the requests in the brief for simple materials, scale, solidity and “unbreakableness” are also apt descriptors of Couch’s work. Coincidentally, Architecture Architecture director Michael Roper is working on a publication about Couch’s projects, and there are allusions to the raw clarity of his work throughout, including galvanized steel window frames, blockwork walls and simple concrete pavers used for flooring inside and out.

Open to the sky, the courtyard spans the full width of the site and separates living and sleeping zones.

Image:

Tom Ross

The existing street facade and front room of the terrace remain in place, as mandated by heritage controls. However, the new additions follow a crisp diagram that Michael refers to as “chequered zoning” – a pattern of spaces and uses spread across the entire rectangular site. The primary zoning is three north–south bands that gradually transition from public to private, with a central courtyard separating living spaces from the more private bedroom wing, which is pushed up against the rear laneway. These three bands are then split into two east–west strips of contrasting character: a narrower strip along the site’s northern edge is low and intimate, while the wider strip on the southern side is tall and generous. A continuous sectional profile unites the new work, with ceilings raking up from the southern boundary to finish high above the flat-roofed compression of the northern zones. These manoeuvres create six different types of space in the new addition alone, each with distinct characteristics of being high or low, public or private, indoor or outdoor.

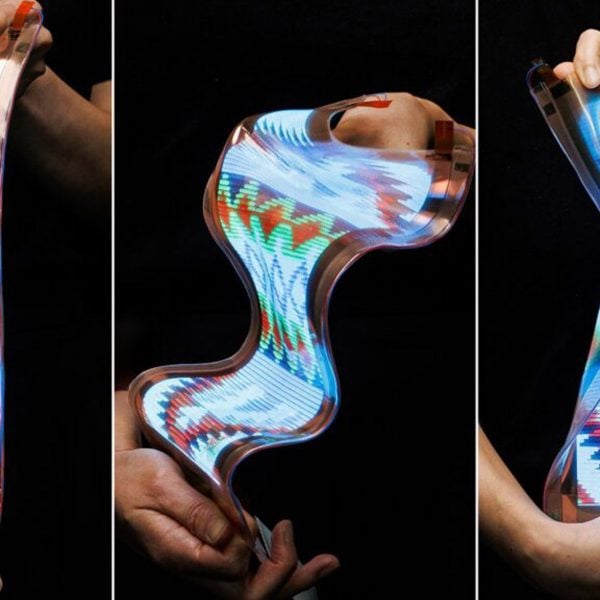

The choice and arrangement of materials increases the impact of the new plan arrangement. Internal and external breezeblock walls filter light and direct views while high-level mirrors blur boundaries and augment the apparent extent of the ceiling. The rows of ceiling joists and stack-bonded blockwork walls continue throughout, their precise lines a testament to the skill of builder Tom Petty. Tom’s unique contributions to the project ranged from the real-time embodied carbon count digitally displayed on the construction hoarding to custom-fabricated hardware, including the seamlessly integrated lighting, a bi-folding wall between the study and the hallway, and a set of delicate vertical timber louvres that control light through the main bedroom’s triangular window.

A sunken yellow daybed is a sun-bathed place for retreat.

Image:

Tom Ross

The most revolutionary design move is so inherent to the diagram of this home that it seems inevitable. The large, central courtyard spans the width of the site, completely separating the bedroom from the living spaces. This outdoor room has been given as much design attention as the internal spaces: rows of timber joists follow the internal ceiling profile, oversailing the garden by Amanda Oliver Gardens and providing an armature for creeping vines, while the vertical fluted glass of the clerestory continues into the courtyard in order to screen views of the looming northern neighbour. The courtyard is open to the sky; an internal or covered connection between sleeping and living zones was considered unnecessary and spatially inefficient. The result is a unique experience in a dense inner-city neighbourhood, a deliberate trade-off between a small degree of inconvenience and unexpected generosity, perfectly suited to two clients who were content to experience the vagaries of Melbourne weather as they traverse their home.

Personal preferences are, refreshingly, found throughout the design of this home, from the sunken yellow lounge with train-carriage proportions to the custom pegboard “cat wall” in the study, an engineered cat door and inset steel recess for a bedside water glass. This is a compact house by Australian standards, achieved through tight editing and by tailoring the design to fit specific inhabitants. The appeal of the small is very big right now. From tiny houses to micro-flats, the fascination with attempts to design around spatial constraints appears endless. But often, the focus is on miniaturizing the typical rather than personally reappraising what one really needs in a home. Architecture Architecture has taken a different approach in Sunday, a major renovation that has deliberately reduced the internal area of a small Fitzroy terrace house, relying instead on big ideas to greatly increase scale, generosity and quality.