[ad_1]

Cultural centre Het Nieuwe Instituut is rethinking the archetypal museum shop with a pop-up at Dutch Design Week, designed to encourage more ethical, resource-conscious consumption.

Instead of offering a straightforward exchange of wares for money, New Store 1.0 gives patrons the opportunity to trade their urine for a piece of Piss Soap and encourages them to place their phones on specially designed fixtures to provide lighting for the venue once the sun goes down.

Taking over Residency for the People – a hybrid restaurant and artist residency in Eindhoven – the pop-up also serves up two different versions of the same seabass dish, one made using wild locally caught fish and the other using fish that was industrially farmed and imported.

The pop-up is the first of two trial runs for the New Store, aimed at helping Rotterdam’s Nieuwe Instituut work out how to design its own museum shop to prioritise positive social and environmental impact over mere financial gain.

In collaboration with the International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam (IABR) and research consultancy The Seeking State, the second trial will take place at next year’s Milan design week, with the aim to open the first dedicated shop in the museum’s Rotterdam location in 2025.

“It all started out with the idea that we don’t have a museum shop per se,” Nieuwe Instituut’s programme manager Nadia Troeman told Dezeen. “A museum shop, as we know, has books and trinkets and gadgets. And it’s not really doing well for the planet or the environment.”

“So we were like, how can we make the act of consuming better? How can we consume differently to help not just ourselves but the environment as well?”

For the Dutch Design Week (DDW) pop-up, Nieuwe Instituut found the three featured projects by Dutch designers Arthur Guilleminot, Brogen Berwick and Arnout Meijer via an open call.

The aim was to help the designers trial their ideas for how the exchange of goods could be less extractive and transactional in a real-world scenario.

“The project is part of a broader institutional agenda of ours to become more of a testing ground,” explained the museum’s director Aric Chen. “It’s part of rethinking the role of cultural institutions as being places that can do more than host debates, discussions and presentations.”

“So our aim is to take some of these projects that try to think about how we can do less damage, take them out of the graduation shows, take them out of the museum galleries, take them out of the biennales and put them into the real world, with real consumers, audiences and real people to see what we can learn from it,” he continued.

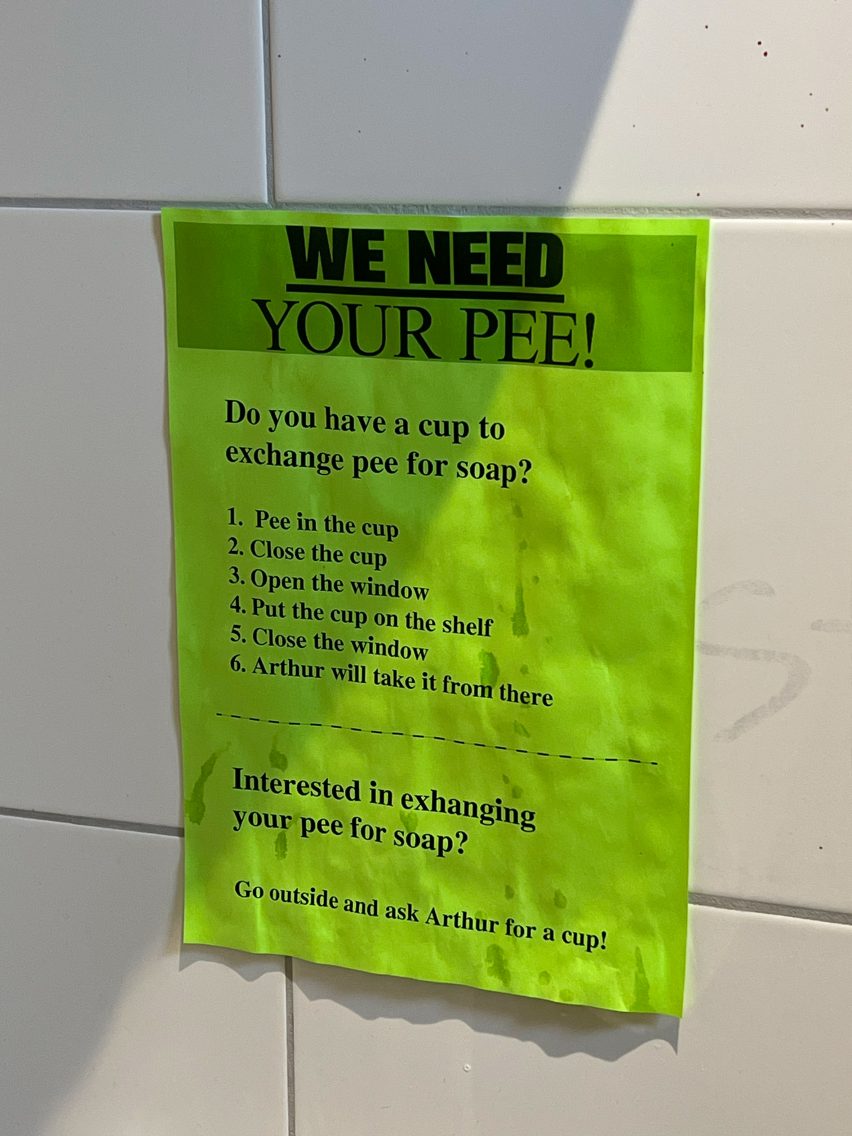

Guilleminot used the opportunity to expand his ongoing Piss Soap project, with a poster in the venue’s toilet inviting visitors to donate their pee by relieving themselves into designated cups and discreetly placing them on a newly added shelf outside the bathroom window.

This can then be exchanged for a piece of soap, made using urine donated by previous participants and other waste materials from human activities such as used cooking oil.

The soap takes three months to cure and is entirely odourless, helping to break up dirt and grease thanks to the urine’s high ammonia content.

The aim of the project is to find a new application for an underutilised waste material and engage people in a kind of circular urine economy.

“The idea was to revive the ancient tradition of using pee to make soap, which was done for many centuries, including in ancient Rome,” said Guilleminot.

“Could I make a modern product using this ingredient and, in the meantime, also change our feelings of disgust about our golden organic liquid?”

Those having dinner at the New Store can choose between two iterations of the same fish dish.

The first uses wild seabass that was caught locally by fishers Jan and Barbara Geertsema-Rodenburg in Lauwersoog while the other was farmed in Turkey and imported by seafood market G&B Yerseke.

Devised by Berwick, who is a design researcher and “occasional fisherwoman”, the project challenges diners to ask themselves whether they are willing to pay the higher price associated with locally caught fish in exchange for its environmental benefits.

“With the fish, they get a receipt of transparency,” Troeman added. “And one is obviously longer than the other.”

Diners were also asked to provide their own illumination as the sun goes down, in a bid to make them aware of our overconsumption of energy and the adverse effects our light pollution has on the natural rhythms of other animals.

For this purpose, Meijer designed two wall-mounted fixtures inside the New Store that have no internal light source and are simply composed of discarded glass shards topped with wooden shelves made from old beams.

If they require more light, guests have to place their phone on this ledge with the flashlight on, funnelling light onto the glass shard through a narrow slit in the wood.

This reflects and refracts light around the space while revealing various crescent moon shapes engraved into the glass in a nod to the circadian rhythm.

“It’s really about our dependence on the constant supply of energy,” Troeman said. “Can we embrace the dark and hence be more environmentally friendly? It has benefits for everyone and everything.”

Exploring more circular forms of exchange was also on the agenda at last year’s Dutch Design Week, when designer Fides Lapidaire encouraged visitors to trade their own poo for “shit sandwiches” topped with vegetables that were fertilised with human waste.

The photography is by Jeph Francissen unless otherwise stated.

Dutch Design Week 2023 is taking over Eindhoven from 21 to 29 October. See Dezeen Events Guide for information about the many other exhibitions, installations and talks taking place throughout the week.

[ad_2]

Source link