[ad_1]

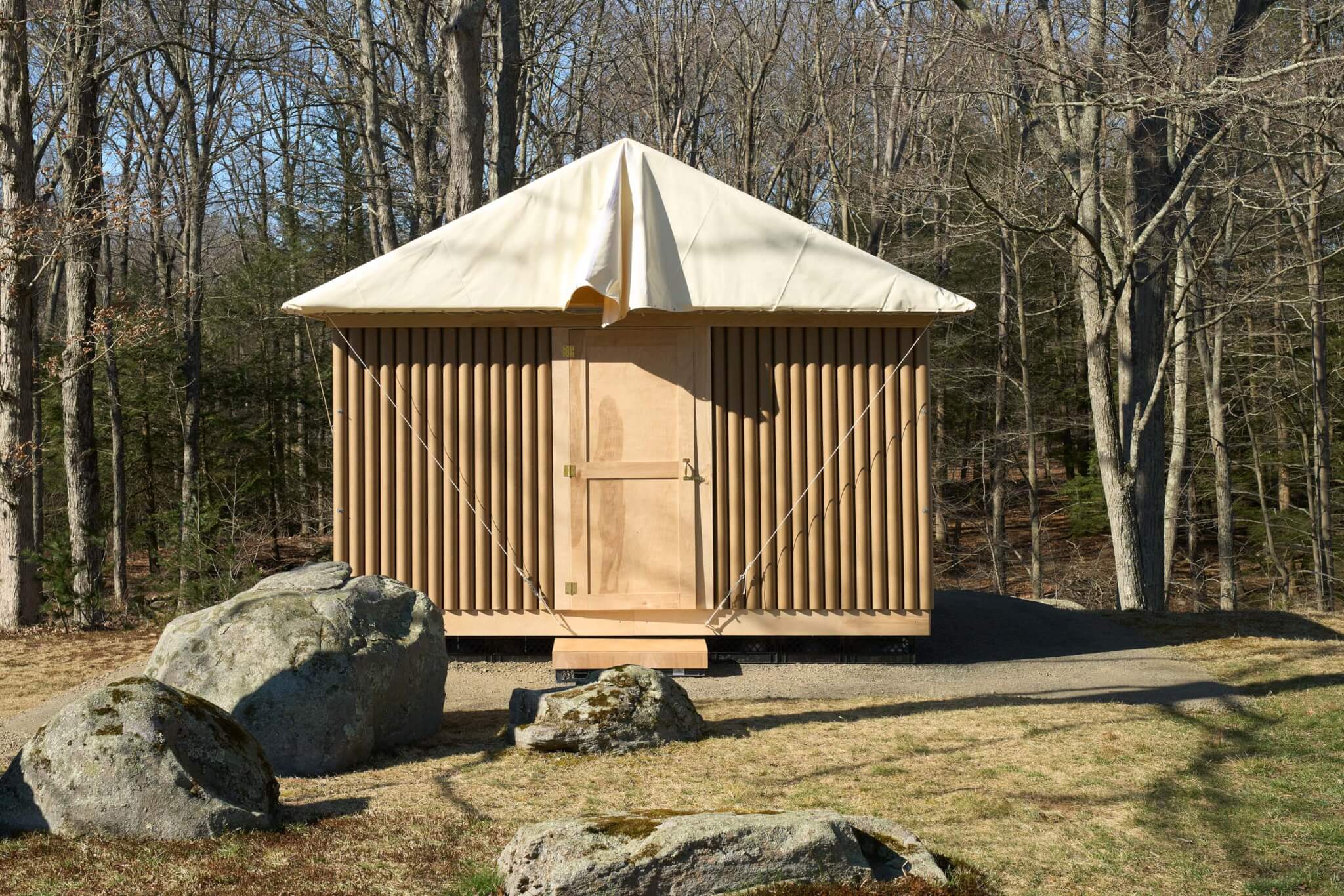

Shigeru Ban Architects (SBA) has installed The Paper Log House on the grounds of Philip Johnson’s Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut. The prefabricated shelter made of paper tubes, canvas, plywood, zip ties, and milk crates will remain on view for the remainder of The Glass House’s 2024 season, which runs until December 15.

Most obviously, the temporary installation has appellative similarities to the site’s permanent architecture—Johnson’s Glass and Brick Houses—structures which foreground materiality in both name and construction. However, The Paper Log House reflects contemporary attitudes in the profession, responding to the challenges of climate changes and the needs of the public in ways that Johnson’s aesthetically driven designs were never intended to. This creates a more interesting contrast than what appears superficially (paper, brick, glass), one that is more concerned with the methods and purpose of construction.

Pritzker Prize–winning architect Shigeru Ban designed The Paper Log House nearly 30 years ago, first deploying it as temporary housing for those displaced by the Great Hanshin Earthquake in Kobe, Japan. In the intervening decades, Ban’s design has been constructed across the globe in response to a variety of natural and humanitarian disasters.

To construct the installation on site, SBA engaged students from The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture at The Cooper Union. The project was organized through a building technology sequence led by Professor Samuel Anderson. It is no accident that The Cooper Union was chosen to participate in the assembly—both Shigeru Ban and Dean Maltz, managing partner at SBA, are alumnus.

Students prefabricated components of the structure, such as its plywood floors and connectors, at The Cooper Union’s campus in Manhattan before transporting the materials via U-Haul Truck to New Canaan.

The Paper Log House was assembled in two days in March by a team of 17, including students and faculty from The Cooper Union, as well as staff members of Shigeru Ban Architects.

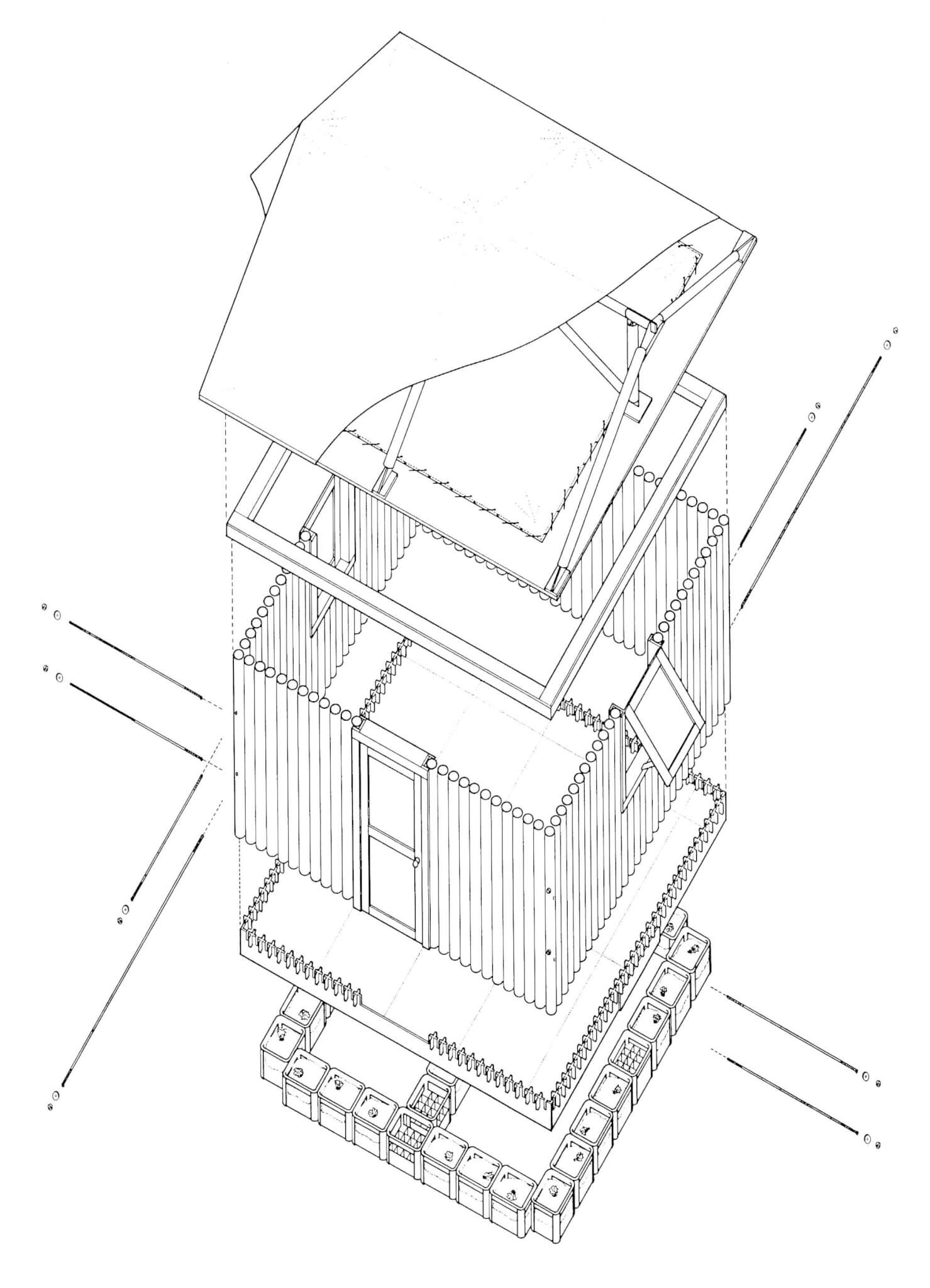

At the Glass House, the shelter stands on a patch of compacted gravel. Its foundation is comprised of milk crates which builders zip tied to plywood floorboards on the interior. Invisible to the visitor are crenellated connector pieces that join the paper tubes to the floor. Once fit to the floorboards, the paper tubes were bound horizontally through the insertion of a threaded rod into predrilled holes.

For the roof structure, students applied paper tube rafters, joining them to the rest of the structure with prefabricated plywood connections. Last, a waterproof membrane was draped over the shelter, and secured using nylon rope.

The relatively small proportions of The Paper Log House— roughly 14 by 14 feet in plan and less than 12 feet in height—allow it to fit comfortably within the pre-existing scale established on the grounds of the Glass House. Johnson’s sprawling estate features a number of his architectural creations, however, none of them are particularly large.

Shigeru Ban’s experimentation with paper tubes as a structural material did not end with the design of The Paper Log House. In 2013, the firm completed the Cardboard Cathedral, a 79-foot-tall structure which partially relies on cardboard for its structure (as well as timber and steel). The architect also delivered a TedTalk on the topic of paper tube construction.

Dean Maltz, who leads SBA’s New York office, addressed the contemporary relevance of the Paper Log House at the Glass House’s 75th Anniversary reception.

“Today, we’re faced with [a] climate crisis. There are more frequent strong weather events that destroy dwellings. Architects have a responsibility to help victims of natural disasters, which has been a lifelong mission for Shigeru Ban and Shigeru Ban Architects,” Maltz said.

[ad_2]

Source link