At the time of writing, Hobart is on the precipice of becoming a campus city as the University of Tasmania plans its $600 million relocation to the CBD from the suburban Sandy Bay campus. The increase in the number of large-scale buildings this will bring to Hobart will have a significant impact on the character and life of the city, particularly for the small, delicate and often climatically challenged CBD.

As the city prepares for this transition, it may well look to other Australian campus cities to discover the unique contribution that universities can make to the sense of identity, cohesion, amenity and quality of the public realm. As large-scale urban developers, universities have a responsibility to ensure and protect the integrity of their developments in the interest of the public. In Melbourne, the campus city model has been particularly successful because its institutions – the University of Melbourne and RMIT University – acknowledge and fulfil their roles as benefactors and quasi-custodians of the public realm.

A subtle connection to context and attention to detail amplify the small project’s civic impact.

Image:

John Gollings

The University of Melbourne’s End-of-Trip (EOT) Facilities for the Southbank campus by Searle x Waldron Architecture (SxWA) provides valuable lessons on how Hobart may protect and strengthen its public realm during this significant change. In program, the project’s significance may seem minimal – bike storage, change rooms, a cafe and coffee stand – but it is a worthy prototype for urban renewal that is sensitive to the vulnerabilities of the city and the university alike.

The project, designed by Suzannah Waldron and her late partner Nick Searle, emerged from a seemingly minor but critical move in the university’s Southbank campus expansion. The bike facility and cafe were extracted from the brief for the Ian Potter Southbank Centre (John Wardle Architects) to become a standalone project. This led to three key distinctions in the campus expansion program that enabled the creation of a more unified public environment.

First, carving off the public infrastructure components created an opportunity for smaller practices to contribute to the campus expansion. Registered on the university’s prequalified list and invited to participate in a closed expression-of-interest process, SxWA won the job based on its pitch that spoke to the values of the client, its observations of the identity of the campus and its scheme to leverage that identity to activate the precinct. The practice worked under the John Wardle Architects’ team, placing it within, yet at a productive distance from, the complexities of the larger project. The critical moves of retaining one part of the heritage postmaster’s garages while demolishing another part to create a public open space were inherited from John Wardle Architects’ masterplan for the site, with the two firms working with Aspect Studios on the linear park between their respective architectural propositions.

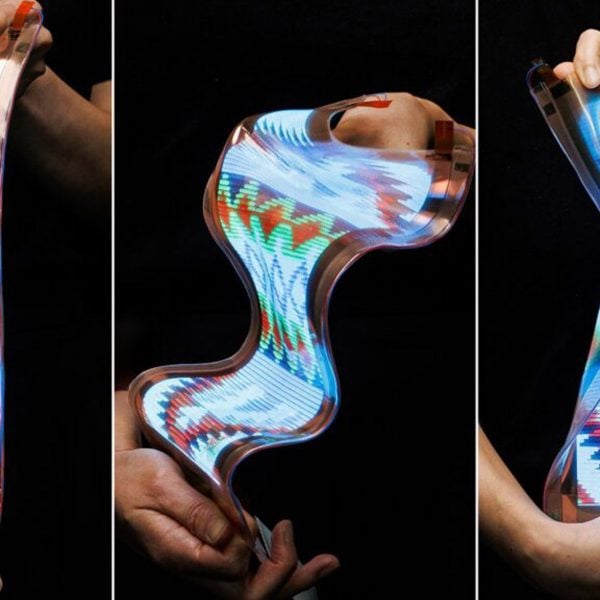

The colourful facade is contorted into an awning form, both revealing and bracing the heritage fabric.

Image:

John Gollings

With a brief that was for, essentially, an amenity shed, there was greater opportunity to exceed expectations than in a big-budget flagship project. That is not to dismiss SxWA’s remarkable achievements as an inevitability. Despite the programmatic simplicity, the practice faced challenges that were complex in other ways – among them, how to activate yet secure the facade, particularly given its adjacency to a key public space. SxWA’s response was a vibrant facade of prefabricated panels made from painted radial timber battens. It includes three timber profile types, 14 colour combinations (including, rather fittingly, the Dulux tones “Five Star” and “Good Samaritan”) and 19,156 individual battens. The mural-like result was inspired by surrounding wall art and adjacent buildings, including Edmond and Corrigan’s Victorian College of the Arts (VCA) School of Drama. Other subtle local references are made, including replication of the repeated lifting and unfolding gestures in the Sturt Street facades of ARM Architecture’s Melbourne Recital Centre, John Wardle Architects’ Ian Potter Southbank Centre and, further along, the Australian Centre of Contemporary Art (ACCA) by Wood Marsh. Such subtle connection to context, combined with a diligent attention to detail, has elevated the mundane into the memorable and created a building that rivals its big-budget neighbours for civic impact.

Comprising bike storage, change rooms, a cafe and a coffee point, the facilities strengthen the cohesion of Melbourne’s public realm.

Image:

John Gollings

The duplicity of roles that the facade system plays is a hallmark of the small project and its regular offsider, a modest budget. The strategy has been used repeatedly: downpipes are housed in the steel verandah posts, an awning is contorted to reveal and brace heritage fabric simultaneously, and a light well reveals the depth of the enclosed volume above a low, sheltered space. These moves inject the building with simplicity and cohesion, and enable it to focus attention on the singular architectural gesture of the civic mural. Creating opportunities for small local practices that are accustomed to resolving complex problems on the smell of an oily rag is critical to ensuring high-quality outcomes in all elements of campus redevelopment.

The second distinction is that because the project is a campus-wide facility available for use by all staff and students, the architect engaged with a relatively wide-ranging stakeholder group and was able to focus on delivering broad urban-realm objectives. Further, working on a campus facility rather than a faculty-focused programmatic brief enabled SxWA to concentrate on the relationship between this project and the university as a whole.

Like the University of Tasmania’s emerging medical and art hubs in Hobart, the University of Melbourne’s new Southbank facilities are co-located with a cluster of public and private cultural institutions. While the Ian Potter Southbank Centre speaks to the formal and programmatic scale of the adjacent institutions, the EOT Facilities link the site back to the established university campus, both physically and architecturally. The predominant pattern of the precinct is a networked collection of exquisite miniatures: over the past decade, many Melbourne architects have contributed key small projects to the campus, among them Minifie van Schaik Architects (VCA Centre for Ideas, 2001 – prior to the VCA becoming an affiliated college of the university in 2006), Lyons (Southbank Hub, 2019), Fender Katsalidis (Buxton Contemporary, 2017) and Kerstin Thompson Architects (The Stables, for The University of Melbourne’s Victorian College of the Arts – School of Art, 2018). While each is distinct in architectural expression, there is a unifying pattern, with each building signposting the entrance to university programs and encouraging occupation through small, human-scaled edges. The EOT Facilities follow suit, with a pushed-in northern edge creating a covered verandah that provides respite for pedestrians and park dwellers in hot or inclement weather, and niches at the two key programmatic entrances to encourage lingering. The southern entry can open wide in the morning, scooping up commuters and creating a waiting space for the coffee stand. The significance of this crucial campus node is elevated through the unexpected opening of the ceiling surface into a skylight. The device is a miniature version of that used in SxWA’s formative Annexe at the Art Gallery of Ballarat. These gestures show that the relaxing of external pressures allowed the architects freedom to create a project that contributes to the architectural lineage of local Melbourne practices on campus and the work of the firm itself.

Opening to the street edges, and encouraging through traffic, the facilities link campus and city.

Image:

John Gollings

Finally, the project demonstrates how urban infrastructure can act as a linking device between campus and city. The location and arrangement of the EOT Facilities and linear park outside the confines of the Ian Potter Southbank Centre mark a fundamental shift in the University of Melbourne’s engagement with its context. Unlike the established St Kilda Road cluster, which replicates the rambling courtyard format of the university’s Parkville campus to the city’s north, this new plaza opens to its street edges. Through traffic is encouraged by clear view lines from Dodd Street to Sturt Street, and the most direct line of travel across the space is facilitated by chipping the southern edge off the new amenity block. For the campus community, cross-site connections are made where the program of the EOT Facilities is bisected by the extension of Workshop Way, linking the Melbourne Conservatorium of Music to art studios and teaching spaces.

There are, nonetheless, ostensible challenges at the intersection of the city and the campus. Unlike public institutions, universities’ contributions to enriching the public realm are voluntary, self-governed and vulnerable to the commercial objectives of each university. Unfortunately, elements of the architectural integrity of this project have been challenged by commercial pressures, specifically the exclusion of SxWA in the design of externally operated programs within the building.

SxWA’s involvement in the campus development illustrates the stewardship role that larger practices undertaking significant university projects have in bringing smaller, local practices along. A similar approach was successfully enacted by Lyons director Carey Lyons in the campus redevelopment at RMIT University (completed in 2017 by Lyons, MvS Architects, NMBW Architects, Harrison and White, Maddison Architects and Taylor Cullity Lethlean). Crucially, this stewardship extends beyond merely creating opportunities for emerging practices to get on board and relies additionally on establishing the right conditions for them to thrive in, ultimately benefiting both the project and the client.