Vaccinium spp.

Blueberries are popular with home gardeners because, let’s face it, they’re delicious. But while the berries get most of the attention, the bushes are beautiful plants in their own right.

Blueberry plants bloom during mid- to late spring – typically in May or June, depending on the species and cultivar – with showy white, pink, or purple flowers.

As the blossoms give way to fruit in the summer, typically July and August, dark green leaves with light undersides provide contrast against the ripening light to dark blue berries.

In the fall, the foliage turns red, orange, purple, yellow, or a mixture of these colors.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

There are five common types of blueberry plants out there, beginning with the most popular in commercial cultivation, the northern highbush (Vaccinium corymbosum).

Next we have the southern highbush, which is a hybrid of V. corymbosum and a native species from Florida known as the evergreen blueberry, V. darrowii.

Then there is the lowbush species (V. angustifolium), which grows low to the ground, staying under two feet tall. It’s native across the US and Canada and the type that people often forage in the wild.

And there is also the rabbiteye species, V. virgatum. These grow native across the southern US and can reach up to 20 feet tall.

Finally, there is the half-high, which is a hybrid of lowbush and highbush blueberries.

Cultivars of each species have been bred to produce fruit that matures at different times – early, midseason, or late.

There’s a lot of interesting and useful information about growing blueberries to cover, so let’s jump right in! Here’s what we’ll go over in the coming sections:

What Sets the Different Common Blueberry Types Apart?

Highbush blueberries (V. corymbosum) are deciduous woody shrubs that can reach up to eight feet tall at maturity.

In contrast, as you might expect from their name, lowbush berries (V. angustifolium) are significantly shorter deciduous woody shrubs.

Sometimes called wild blueberries, these only reach heights of about two feet tall.

Besides size, another way in which the available types differ pertains to gardening region. Some highbush and rabbiteye plants can grow in warmer climates, while lowbush varieties can tolerate cooler climates. Half-high blueberries sit somewhere in the middle.

Highbush types grow best in USDA Hardiness Zones 4-8, while lowbush types grow comfortably in Zones 2-7. Half-high bushes grow best in Zones 3-7. It is possible, however, to find specific cultivars that can grow outside of these ranges.

Why the difference? It isn’t just that highbush plants can’t handle extended periods of freezing temperatures, but since they’re so tall, stems can break and they can be crushed under heavy snow. Lowbush plants, on the other hand, don’t mind a thick blanket of snow.

These species are further broken down into northern and southern varieties, with narrower ranges of suitable climate.

For example, northern highbush and lowbush blueberries need about 800-1,000 chilling hours, while southern highbush plants need about 150-800 hours, depending on the cultivar.

Half-high bushes, as you might expect, need something in the middle, usually around 800 hours.

What’s that, you ask?

“Chill hours” refers to the number of hours that temperatures need to be somewhere between 32° and 45°F in the winter in order for the plants to produce flowers and fruit the following spring and summer.

A bit of an outlier, rabbiteye blueberries (V. virgatum) stand out because they ripen about a month later than lowbush or highbush types, and the berries are smaller and sweeter, with a tougher skin.

The immature berries are creamy white or pink in color with a bright red or pink calyx, giving the fruit the appearance of an albino rabbit’s eye.

Rabbiteye bushes can grow up to 20 feet tall and are a bit more tolerant of dry conditions or drought than other types. They aren’t able to tolerate a lot of water, like other kinds of blueberries can.

Rabbiteyes grow best in Zones 7-9 and need between 300-700 chilling hours, depending on the cultivar.

Cultivation and History

Berries in the Vaccinium genus grow wild across the world.

For instance, in northern continental Europe, Ireland, the British Isles, Iceland, and northern Asia, you can find the native European blueberry (V. myrtillus), also known as the forest blueberry or bilberry.

In South America, you can find the mortiño (V. floribundum) and the Jamaican bilberry (V. meridionale).

But when we talk about the blueberries you’re likely to find at the store, we’re usually talking about the plants native to North America.

Originally, all blueberries growing in North America were uncultivated lowbush or rabbiteye plants, along with a few other species like V. alaskaense, or the Alaskan blueberry, and V. ovalifolium, or the oval-leaf blueberry).

Scientists think the blueberry was one of the first fruit plants on the continent to be utilized by humans after the last ice age.

It was thanks to the indigenous populations living in what became known as the United States that European settlers learned about this magnificent fruit.

Native Americans ate the berries fresh when they were in season, cooked them into stews and meats, baked with them, and dried them to be eaten during the winter. They also used them medicinally.

People continued to harvest, eat, and preserve wild blueberries exclusively, until Elizabeth Coleman White and Frederick V. Coville came along.

White worked on her parents’ cranberry farm in the late 1800s. At the time, growers didn’t think the wild blueberry could be cultivated, but White believed she could make it happen.

She reached out to Coville, a botanist with the USDA who was also studying wild blueberries, and the pair worked together to create the first domesticated highbush blueberry.

These days, northern highbush are the most common commercially grown blueberry in North America and the berries that you see at the grocery store in those plastic clamshells or berry baskets are usually highbush types.

The southern highbush has only been cultivated for the past six decades or so. It is a hybrid of northern highbush and rabbiteye or evergreen varieties.

But that doesn’t mean the lowbush blueberry isn’t around anymore. It’s an important crop in the northeastern United States and Canada, where it is cultivated or harvested from managed wild stands.

These berries are usually sold either canned or frozen because they don’t store or ship well, though you can find them fresh locally during the growing season.

Rabbiteyes are grown commercially in the southeastern United States, and if you’re lucky enough to live in the region, you can find the fruits fresh at markets and grocery stores during the summer.

While North American blueberry species are cultivated across the globe, from Australia to Siberia, a majority of the commercially grown berries sold worldwide come from the US.

Propagation

You have lots of options when it comes to propagating your plants.

Bare roots, cuttings, and transplants are easiest, but if you want a growing adventure, you can also cultivate them by starting seeds.

Whichever method you choose, be sure to prep your soil well before sticking your new plants in the ground. If you need to alter your soil much, it can be a lengthy process.

For instance, if you have clay or sandy soil, working in some composted pine or fir sawdust repeatedly over several months can help create the right conditions for blueberries.

From Seed

Beginning with the most challenging option, you can grow blueberries from seed, but it will obviously take longer to produce your first harvest than it would if you started with established plants.

Seeds can be purchased or you can extract them from the berries. Keep in mind that seeds from hybrid plants won’t grow true to the parent.

To extract seeds, place a cup of blueberries in a blender with four cups of water. Run it on high for 15 seconds and then let the mixture sit for 10 minutes.

Eventually, the pulp will rise to the top and the seeds will sink to the bottom.

Pour out the pulp, add more water to replace what you poured out, and set it aside for another five minutes. Repeat until you get clear water with blueberry seeds at the bottom.

A few months before the last frost date in your area, sprinkle your seeds over a container filled with moistened peat moss.

Place a thin layer of peat on top to cover. Cover the tray with a piece of plastic or a humidity dome to keep the moisture in. Keep the seeds around 60-70°F.

Now comes the waiting game. Every time I’ve done this I’m pretty sure my seeds are duds and I get ready to toss the whole thing out, only to see the little green seedlings stick their heads out of the peat.

That’s because it can take a month or two – or sometimes three! – for seeds to germinate. And I’m impatient.

Once seedlings are about three inches tall, remove them from the peat and put each one in a six-inch pot filled with equal parts peat, sand, and potting soil.

Keep the medium moist but not wet, and put the seedlings in a spot where they receive about six hours of sun a day.

Once the danger of frost has passed, you can put the plants in the ground outside, but be sure to harden them off for a week before transplanting them to their permanent home.

Harden off seedlings by placing them outside in a sheltered spot with indirect light for one hour, and then bring it back indoors. Repeat this, adding an hour each day for a week, until they can spend the full day outside.

Because the seeds need such carefully controlled conditions, direct sowing in the garden isn’t recommended.

By Cuttings

If you have access to an older, healthy blueberry bush, you can take hardwood cuttings to start new plants.

In the late winter when the plant is still dormant, take a six-inch cutting from one-year-old wood. You want a cutting that is about as thick as a pencil.

Cut the end you’ll be burying at an angle to assist in sinking it into the soil and to increase the surface area for water and nutrient uptake.

Bury the cutting two inches deep in a container filled with equal parts sand, peat moss, and potting soil.

I like to use four- or six-inch containers, preferably a compostable type like CowPots.

CowPots Biodegradable Pots

Arbico Organics sells these handy pots in packs of 12, 180, or 450 – for those serious gardeners!

Keep the potting medium moist but not wet. In about three months, your cutting should develop roots. You’ll know this is the case if you give the cutting a gentle tug and it resists.

Once the risk of frost has passed, harden off the rooted cutting as described above, and then plant it in its permanent spot.

Dig a hole twice as wide and as deep as the container the cutting was growing in. Put the plant in the hole, spreading out the roots. Backfill with soil and pine or fir sawdust, if using.

Rooted cuttings will take about two or three years more than transplants to produce berries.

By Bare Root

Bare root plants are generally more affordable than transplants, but they take a bit of extra prep to propagate.

If you can’t plant yours right away after your order arrives or you bring them home from the nursery, put them in a cool, dark place. You don’t want to let the roots dry out, so spray them daily with a water bottle.

When you’re ready to plant, soak the roots in room temperature water for three to six hours. Remove from the water and cut away any broken roots.

Then, spread the roots out horizontally rather than down and dig a hole that is a few inches wider and the same depth as the roots.

These shrubs prefer to have their roots close to the surface of the soil rather than down deep, so we’re trying to recreate their natural growing habit when we do this.

Place in the hole and backfill with soil that you dug up. Water well to settle the soil.

Transplanting

If you’re in a hurry to dig into those sweet berries, you can purchase one, two, or three-year-old blueberry transplants.

Most plants start producing at about two years old, so you could be digging in right away, though your first harvest may be small.

Transplants should be planted in the fall or spring, depending on where you live. Gardeners in warmer regions like the Pacific Northwest or the Southeast should put plants in the ground in October, March, or April.

In cooler regions like New England, spring is best in order to allow the plant time to become established before winter rolls around.

When you are ready to plant, gently remove it from its container and be sure to thoroughly loosen up the root ball. Spread the roots out, not down.

When you’re done, the root system should be about twice as wide and half as deep as it was while confined to the pot it came in.

Dig a hole slightly wider than your newly spread-out root ball and about the same depth.

You may want to work some peat or compost into the surrounding soil if the texture of your earth is different from the soil the transplant was growing in. This helps to improve aeration and encourages the roots to expand.

For instance, if your potted blueberry is in a loamy potting mixture, but your native soil is quite sandy, you’ll need to amend your soil to encourage the roots to extend into your native soil.

You can learn more about how to transplant blueberries in our guide. (coming soon!)

How to Grow

Blueberries are ericaceous plants, along with other acid-lovers like rhododendrons, azaleas, and hydrangeas. They all like similar acidic soil conditions.

You can also grow them near trees that thrive in acidic soil, such as some pines. Just remember, there’s a common garden myth out there that pine needles make the soil acidic.

That’s not true. Don’t assume that you can plant your blueberries near a pine tree and the soil will have the right pH.

Blueberry plants need acidic soil with a pH between 4.0 and 6.0, depending on the species. All blueberries need soil that is porous, with lots of organic matter. But they don’t need a ton of additional nutrients.

Test your soil a year before planting so you will have time to make amendments to adjust the pH – if you need to – before putting your new blueberries in the ground.

Keep in mind, however, that rabbiteye blueberries don’t do well in soil that doesn’t naturally have a pH at or below 5.5.

If your soil has a higher pH level than this, either build a raised bed and fill it with acidic soil, or plant somewhere that does have the ideal pH, rather than using a soil amendment like sulfur to change the pH.

These plants need an even balance of nitrogen, potassium, and phosphorus. That means if your soil is deficient in one of these nutrients, you’ll need to add it.

For instance, if your earth is low in nitrogen, you’ll want to work in something like blood meal to add nitrogen.

After conducting your soil test, amend with any necessary fertilizer before planting your new bushes, and let the granules dissolve for a week or two. Fertilizer granules that touch young roots directly can burn them.

If your soil isn’t naturally loamy, work in some aged fir or pine sawdust, or finely chopped bark, to improve aeration.

You can lower the pH by adding pelletized or granular elemental sulfur or peat moss to the soil, following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Sulfur takes about a year to alter soil pH.

Alternately, you can also use aluminum sulfate, or iron sulfate. These work faster, but you need to be careful not to add too much. It’s easy to overdo it with sulfates.

While you’re testing and improving your soil before you plant, you should also remove any weeds from the area. Blueberry plants don’t like to compete for nutrients, sun, or moisture.

That’s because they have shallow root systems, without big tap roots to dig deep into the soil for water and food.

You can also plant a cover crop to help improve the soil and beat back weeds. Rye, buckwheat, or sudangrass (Sorghum x drummondii) all work well for this purpose.

Consider using raised beds if you need to amend your soil to suit blueberries. Whether the soil lacks nutrients or needs pH adjustment, or if you have heavy, compacted or clay soil, you might want to construct a few raised beds to plant in.

This gives you the ability to alter the soil without impacting the surrounding area.

You can build a wooden box, or just hill up some improved soil if you prefer. If you have heavy soil, you can also work in some sand to improve drainage.

You should group blueberries together, rather than spreading them out around your garden. That makes it easier to keep the soil pH at the right level, which is key to an abundant harvest. It also helps the plants pollinate each other.

Not all blueberries need a companion for pollination, but many do. This means you need to plant cultivars together that bloom at the same time.

Southern highbushes need to be planted with a cultivar that blooms at the same time, and this will typically be noted in the plant description or on the growing tag from the nursery.

Rabbiteye blueberries also need a companion for pollination. Again, be sure to pick cultivars that bloom at a similar time.

‘Alapaha,’ ‘Climax,’ ‘Premier,’ ‘Prince,’ ‘Savory,’ and ‘Vernon’ are all early bloomers.

‘Austin,’ ‘Brightwell,’ ‘Columbus,’ ‘Montgomery,’ ‘Powderblue,’ and ‘Tifblue’ all bloom mid-season.

‘DeSoto,’ ‘Ochlockonee,’ and ‘Onslow’ are late bloomers.

Most highbush cultivars are self-fertile, but cross-pollination will typically give you a larger harvest and bigger berries.

While harvest dates can vary dramatically among different cultivars, most northern highbush plants bloom within a week or so of each other. For that reason, all cultivars can be used for cross-pollination.

Native bees, bumblebees, and honeybees are the only pollinators of blueberries. The flowers can’t be pollinated by birds or butterflies because they require “buzz pollination.” This happens when a bee vibrates or shakes the pollen loose from a flower.

Large highbush species should be spaced around four to six feet apart, and dwarf cultivars about two to four feet apart.

Rabbiteye bushes need more space, with at least six feet between plants, but preferably more. Lowbush blueberries can be planted one to two feet apart.

Most blueberries like a lot of moisture, and those that are growing in the wild can often be found near water, or in swampy or boggy areas.

However, rabbiteye blueberries are more drought tolerant and will suffer if given too much water.

To complicate things, blueberries have very shallow roots. That means they dry out easily, so they need consistent watering.

Plants require one to two inches of water a week, depending on the species. You can use a rain gauge to help determine how much precipitation you receive.

If you don’t get that much naturally, you’ll need to provide supplemental irrigation.

Mulches like aged pine needles, wood chips, and bark are ideal for helping to retain moisture. Don’t use dyed or synthetic mulches because they may have a negative impact on the environment.

While it may be tempting, don’t use homemade compost around blueberries unless you’ve checked its pH first – it’s usually too alkaline for their liking. Manure-based composts are almost always too alkaline, so it is best to avoid them.

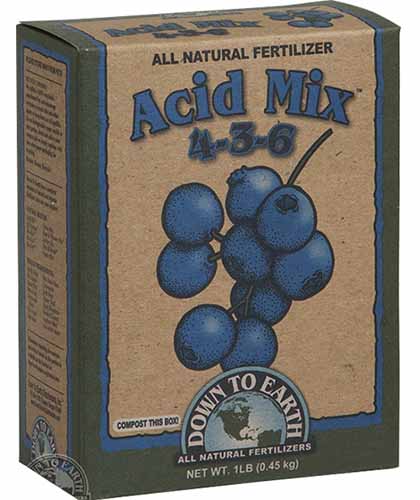

When it comes to fertilizing, wait until the plants have been in the ground for about six months before you apply any food.

Then, apply a tablespoon fertilizer formulated for acid-loving plants every six weeks, extending the fertilizer out 12 inches in a circle around the plant.

Arbico Organics carries Down To Earth’s Acid Mix, which is perfect for blueberries. It comes in one or five-pound boxes – or pallets of 25 or 50 pounds, if you’re planning on going big!

Down To Earth Acid Mix

In the second year, start fertilizing right as new growth emerges and again every six weeks. Apply two tablespoons of fertilizer per plant, extending 18 inches out from the center.

From the third year on, apply a cup of fertilizer per plant spread three feet around the perimeter.

Avoid using commercial fertilizers or using too much fertilizer at once on rabbiteye plants. They’re particularly sensitive.

Growing Tips

- Plant in full sun.

- Maintain soil pH of 4.0-6.0.

- Provide 1-2 inches of water per week if rain doesn’t provide it.

Pruning and Maintenance

If you’re going to grow blueberries, you’ll need to become good friends with your pruning tools.

Regular pruning is effective for managing insects, it helps to prevent disease, and it encourages more abundant harvests and larger fruits. Plus, it makes it easier to harvest the fruits when they’re ready to pick.

Older canes produce smaller fruit and less of it. They also compete with the younger, more productive canes for nutrition and light. In other words, they eventually need to go.

The best fruit forms on one-year-old canes and new shoots.

For the first two years of a plant’s life, you don’t need to do much work. Just remove the flower buds by snipping or rubbing them off.

You want the plants to focus on maturing and developing rather than producing berries, tempting though it may be to see your first harvest as soon as possible.

In the spring of the third year when the plant is still dormant, remove any canes that cross, any that are twisted, or any that are growing low along the ground.

Plants should fully emerge from dormancy by the end of March in most areas, and you want to complete your pruning prior to this.

Remove any older canes that weren’t productive in the previous season. To do so, just cut the canes down cleanly at the base of the plant using a clean pair of clippers or pruners.

Then, remove all but two or three of the largest, tallest, most robust new canes that were produced in the previous year. New canes are small, pliable, and often red or darker in color than older canes. You’ll repeat this every year.

Once the plant reaches its mature size, usually around eight years of age, it will typically have about 10 to 20 canes of various ages if you’ve kept up with your pruning.

Going forward, remove any diseased or damaged canes each spring. Then, remove any older canes that are larger than one inch in diameter.

They’ll likely be gray rather than brown or red, and the bark may be peeling. Don’t remove more than 20 percent of the old canes at a time.

If the plant looks crowded in the middle, thin out some canes to improve airflow. As you did in the first year, remove canes that are crossing and rubbing against each other each following year.

You should also remove any canes that don’t have healthy fruit buds and vegetative buds at the end simultaneously.

Blueberry canes can have both fruit buds, spots where the blossoms and fruits will emerge, and vegetative buds, spots where the leaves will emerge. Any cane that has nothing but vegetative buds or no buds at all should be removed.

How can you identify these? Fruit buds appear at the end of cane shoots. They look like teardrop-shaped, swollen buds that will form into clusters of flowers and fruit.

Lower down the canes from those are smaller, pointed buds. These grow new vegetative shoots in the following year.

Wear protective clothing while you are pruning. Gloves, glasses, and a long-sleeved jacket are all good ideas, because blueberry bushes can be rough.

If you have multiple lowbush blueberries, you can simply mow a few down to the ground each year with a lawn mower or weed wacker.

The plants that you mow down won’t produce the next year, so you want to make sure to leave two productive plants alone and alternate mowing. Otherwise, you can prune them as you would taller blueberries.

You may also want to trim the edges of the bushes to limit how far out they spread.

Feel free to give rabbiteye bushes a haircut in order to keep their height low enough that you can reach all those berries. Just don’t take more than a third of the height off at a time.

Otherwise, leave the plants tall and consider the higher berries a sacrifice to our avian friends. They’re nice to have around because they keep insects under control in the garden – we’ll get into a more detailed discussion of pests in a minute.

Blueberries of all species do best with a lot of mulch because it cools the soil and helps retain moisture.

Each year, you’ll need to add mulch so that your bushes always have three or four inches at a minimum around the base (six inches is even better), and extend it out for two feet around them.

You’ll want to remove some or most of the existing mulch before you add some fresh stuff.

The mulch should be flat around the canes, not heaping up higher around the base of the plant. But it’s fine if the mulch is touching the canes – in fact, it should be if you’re doing it right.

Cultivars to Select

If you’re looking for an idea of which blueberries to grow in your berry patch, we have a guide just for you, with 10 top varieties.

Below are a few additional options that we also think stand out.

Alapaha

Many rabbiteye cultivars out there are a little antiquated, meaning they were developed decades ago and have not evolved since, but there have been some great improvements in recent years.

‘Alapaha’ is one of those newer cultivars that is worth tracking down.

It has stellar medium-sized fruits that ripen in the late spring. But despite its early ripening time, it flowers later than most early-blooming rabbiteyes, so it is less likely to be impacted by a late frost.

It only grows about six feet tall, so it stays a manageable size, and requires 450-500 chill hours. Consider planting with ‘Ochlockonee’ or ‘Titan.’

Cabernet Splash

If you’re looking for a blueberry that can do double duty, northern highbush ‘Cabernet Splash’ is a good option.

The four-foot-tall plant has dark red foliage in the spring that gradually turns green as the days heat up. In the fall, it turns a vibrant red.

‘Cabernet Splash’

And, oh yeah, don’t forget the fruit. It produces sweet, juicy berries, with a large yield on each plant. This cultivar needs about 800 chill hours and grows best in Zones 4-7.

Nature Hills Nursery carries 18 to 30-month-old plants if you’re looking to buy one of your own.

Chippewa

‘Chippewa’ is a half-high blueberry that’s hardy in Zones 3-7.

It was bred at the University of Minnesota with the goal in mind to create a four-foot-tall plant that has beautiful, large leaves and a massive yield of up to six pounds of sweet, medium to large berries per plant.

‘Chippewa’

This type is self-fertile and only needs about 800 chill hours, compared to up to 1,200 that are required for other half-high cultivars.

Nature Hills Nursery sells 18 to 30-month-old bushes that are ready to add to your garden.

Rubel

‘Rubel’ is another northern highbush. This one grows best in Zones 3-7 and produces up to 15 pounds of small, tart berries per seven-foot-tall bush.

‘Rubel’

It needs about 800 chill hours per season.

If you want one of these gems for your garden, head to the Arbor Day Store to pick up a 12 to 18-inch bare root plant.

Tophat

‘Tophat’ is a lowbush cultivar that retains that wild blueberry flavor. It’s self-fertile and dwarf in size, so it doesn’t grow taller than about 19 inches – perfect if you want a container blueberry.

Despite its diminutive size, you’ll get up to five pounds of tiny berries from this plant. It’s suited to Zones 3-7 and needs about 1,000 chill hours.

Managing Pests and Disease

Blueberries aren’t entirely free from pests and diseases, unfortunately. Some issues are easily addressed, while others can be nearly impossible to eliminate. Let’s take a look at what you may face.

Birds

Birds love blueberries as much as people do, and who can blame them?

Since I couldn’t possibly consume all the berries that my bushes grow, I let the birds have at them. But hungry birds can consume quite a number of berries, so if you want to protect your harvest, use bird netting.

String netting over plants as soon as the first berries begin to turn from green to blue.

While this isn’t the most tried-and-true option, you can also use grape Kool-Aid or sugar to control birds. Sounds weird, right? But they can help.

Grape flavored Kool-Aid has methyl anthranilate in it, and birds don’t like it one bit. Mix four packs of the unsweetened stuff with one gallon of water and spray plants when berries start to turn blue. You’ll need to reapply every few weeks.

You can also spray plants with five pounds of sugar dissolved into two quarts of water. Spray every few weeks as berries start to ripen. You should also spray after rain.

Most fruit-eating birds can’t digest the disaccharides in table sugar easily, so they won’t go after the plants.

If you find that this spray attracts ants, sprinkle a thin layer of diatomaceous earth (DE) about a foot around the base of your bushes.

Keep in mind that these sprays aren’t as effective as netting, so you may want to stick with netting if you have a serious problem.

Deer

Deer also love to munch on blueberries – both the fruit and the plants. Fencing and commercial repellents are your best options.

Read more about how to install DIY deer fencing here.

Insects

Blueberries are troubled by a handful of insect pests, and a few of the ones that do bother them can be devastating, so keep an eye out.

Blueberry Maggots

This pest is the larvae of the blueberry fruit fly, Rhagoletis mendax. The flies lay their eggs as berries start to turn blue.

Common in the eastern half of the US, the adults can be identified by the zigzagging black bands on their white bodies.

Red sticky ball traps can be an effective way to catch the adults before they lay their eggs. If you promptly harvest your ripe berries, this can also help to control populations.

Apple Maggot Trap Kit

Arbico Organics carries a kit with enough balls to protect a home blueberry garden.

Japanese Beetles

Japanese beetles, Popillia japonica, like to nibble on the leaves of blueberry bushes.

While the plants can handle up to a fourth of their foliage being damaged, if you have a bad infestation, you’ll need to take action.

You can hand pick the beetles and drown them in soapy water.

Learn more about how to control Japanese beetles in our guide.

Yellow-Necked Caterpillars

If you spot hairy little caterpillars with black and yellow stripes, these are likely yellow-necked caterpillars, Datana ministra.

These pests show up as summer starts to wane. In large enough numbers, they can totally strip a bush of all of its foliage.

Spray infested areas with Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt).

Diseases

Keep an eye out for the following diseases.

There are no cultivars that are resistant to everything, and not all diseases occur in all areas, so you might want to check with your local extension office to find out what to grow in your area to avoid problems.

Anthracnose Fruit Rot

This is a common disease that impacts all species of blueberries. It’s caused by the fungi Colletotrichum acutatum and C. gloeosporioides.

The fungi attack plants particularly during warm, hot weather. Severe infections can lead to serious crop loss.

You won’t see symptoms initially, but as the fruits ripen, they will eventually start to shrivel and small blisters will break out on the skin of the berries. Eventually, these will fall off the bush.

But it is also possible for this disease to go undetected until after the berries have been harvested, when they start to rot in storage.

Since you might not know your plants have this disease until it’s too late, prevention is essential. Provide appropriate spacing when planting, water at the soil level, and keep plants well-pruned. Harvest fruit as soon as it is ripe.

Botrytis Blight

The fungus Botrytis cinerea hits during cool, wet weather when plants are blooming. It causes green growth to die back, but the real problem is that fruits will rot after they’re harvested.

Keeping plants well pruned to improve air circulation is key. You also want to make sure you aren’t giving plants too much nitrogen.

You can apply a copper-based fungicide according to the manufacturer’s directions when blossoms are present.

Cane or Stem Canker

Stem canker, also known as cane canker caused by the fungus Botryosphaeria corticis, is especially common in warmer areas like the southern United States.

It causes canes to thicken and form deep cracks. Rather than damaging the entire cane, you’ll see short sections impacted. Eventually, the canes will die.

The best option is prevention. Always prune away any canes or stems that show signs of infection as well as any dead canes, whether they are infected or not.

If you know this disease is a common problem in your area, check the information tag on the plant when you buy, and pick resistant cultivars.

Rabbiteyes are generally impacted less and will continue to produce even if they show signs of cane or stem canker. Highbush plants are more susceptible, but there are many resistant cultivars available.

Chlorosis

All species of blueberries are susceptible to chlorosis, which causes the leaves of the bush to turn yellow or red.

Not technically a disease but a physiological disorder caused by improper growing conditions, this issue is avoidable – but you often won’t realize it’s a problem until you see symptoms.

A high soil pH will cause chlorosis in any species of blueberries, but rabbiteyes are particularly susceptible.

Rabbiteyes may also come down with chlorosis when they’re overfertilized.

In highbush and lowbush types, lack of iron is a more common cause of yellowing than soil pH. Rabbiteyes can become iron deficient as well. Usually, the yellowing will start in the spring or early summer.

Spray plants with chelated iron from your local garden supply store. This is a short-term fix while you sort out fixing the soil. Long term, add sulfur or iron sulfate to the earth, as needed.

Chlorosis can also be caused by stress, which reduces the uptake of iron. If you live in a place where temperatures go above 85°F, be absolutely sure that your plant has enough mulch to protect the roots from heat stress.

Mummy Berry

Mummy berry, caused by the fungus Monilinia vaccinii-corymbosi, can be devastating. It overwinters in fallen fruit on the ground.

With the arrival of spring, the fungus emerges and infects the leaves and flowers.

It causes flowers to turn brown, wither, and die. Leaves and shoots develop black centers and will eventually wilt and die.

Infected berries turn red or tan instead of green, and they often fall off the plant early. Once they’ve fully mummified, the berries turn gray, and become shriveled and hard.

Harvest and destroy any mummified fruit before it falls. You need to be diligent and keep at it for years sometimes, but eventually, the plant can recover.

You can also keep an eye out for resistant varieties if this disease is common in your area.

Harvesting

Blueberries start producing fruits at about two to three years old, but they won’t reach peak production or attain their full mature size until they’re seven to eight years old.

Depending on the species, you can expect to harvest anywhere from under a pound of berries on some lowbush cultivars to 30 pounds or more on some rabbiteye cultivars.

Let the berries ripen fully on the plant before harvesting them. Some species of blueberries, such as rabbiteyes, are non-climacteric, which means the fruit needs to stay on the plant in order to ripen.

Put simply, non-climacteric fruit has a reduction in respiratory activity and stops producing ethylene after it is picked.

Rather than continuing to turn starch into sugar, non-climacteric fruits start rotting once they leave the plant.

For highbush and lowbush plants, look for berries with a blue stem that are dull or matte. These should detach easily. Fruit with green or red stems or shiny berries aren’t ready to pick.

Rabbiteye blueberries turn their mature color well before they are actually ripe. Wait a few weeks after they’ve turned blue and then pull a sample berry off the bush.

It should come away easily and will be sweet and juicy, with a waxy bloom on the skin.

All berries in a cluster may not be ripe at the same time, so try to avoid picking the unripe ones. Pluck the fruits by hand, and place them in a basket or bucket.

Cool the berries immediately after picking to preserve their shelf life. Don’t wash them until you’re ready to eat them, but remove any debris like leaves or shoots that may have come off the plants while you were harvesting.

For more tips, read our comprehensive guide to harvesting blueberries. (coming soon!)

Preserving

Blueberries are full of antioxidants and contain more iron than almost any other fruits that grow in temperate climates.

They’ll last in the fridge for up to 10 days, but they’re best enjoyed three to five days after coming off the plant for the best texture and flavor.

Anything you can’t eat in time can be frozen. It doesn’t take much prep, just wash them, place them in a single layer on a baking sheet, and freeze for a few hours.

Then transfer them to sealed bags. They can keep in the freezer for up to six months.

You can also smoke blueberries. With a little acid, some oil, and a smoker, you’re good to go. Combine two quarts of blueberries with the zest and juice of one lemon.

Add two tablespoons of olive oil. Smoke for four hours with cherry wood chips.

Of course, you can always turn them into jam as well, or pie filling, if canning is your thing.

Finally, consider drying them. This can be done in a dehydrator, or in the oven. Heat the oven to 225°F and place the fruits in a single layer on a cookie sheet.

Don’t pack them too tight, and be sure to leave a little space between the berries.

Bake for about two hours until they’re shrunken but not hard. They should be supple but firm. Allow them to cool and then place the berries in sealed containers and store in a cool, dark place.

They can last for up to 18 months when processed and stored this way.

Recipes and Cooking Ideas

Of course, you can use blueberries anywhere you would use berries.

Who hasn’t tossed a handful on their yogurt or waffles in the morning? Our sister site, Foodal has a tasty recipe for maple roasted blueberries on einkorn porridge.

Or how about a healthy breakfast quinoa with blueberries?

They’re also delicious in desserts. Check out Foodal’s recipe for Blueberry Peach Crisp.

Don’t forget lunch and dinner, too! The mashed berries are delicious baked on fish or white meat.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Perennial berry | Tolerance: | Heavy soil, flooding (depending on species) |

| Native to: | North America | Maintenance: | Medium |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 2-9 | Soil Type: | Sandy, loamy, high in organic matter |

| Season: | Spring-fall | Soil pH: | 4.0-6.0 |

| Exposure: | Full sun to part shade | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Time to Maturity: | 3 years | Attracts: | Butterflies, bees, birds, deer and other berry-eating mammals |

| Spacing: | 4-6 feet (standard), 2-4 feet (smaller varieties) | Companion Planting: | Azaleas, basil, camellias, ornamental grasses, parsley, rhododendrons |

| Planting Depth: | 1/4 inch (seeds), same depth as container (transplants) | Avoid Planting With: | Plants that prefer alkaline soil, such as asparagus, beets, forsythia, garlic, lilacs, kale |

| Height: | 1-20 feet, depending on variety | Family: | Ericaceae |

| Spread: | 18 inches – 6 feet | Genus: | Vaccinium |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Species: | Angustifolium, corymbosum, darrowii, virgatum |

| Common Pests: | Birds, blueberry maggots, deer, Japanese beetles, yellow-necked caterpillars | Common Diseases: | Anthracnose, botrytis blight, cane or stem canker, chlorosis, mummy berry, ripe rot |

Blueberries Are a Bountiful Bush for Your Berry Patch

Blueberries are the kind of plant that I like to have around even if I don’t plan on eating the fruits.

They add so much beauty to the garden, and if you aren’t interested in the harvest, the wildlife will thank you for the tasty snack.

Still, most of us humans are after those juicy, sweet berries, and for good reason. They’re nutritious on top of being delicious.

Once your plants are thriving, I’d love to hear how you plan to use up your crop. I’m always looking for new ideas! Share your tips in the comments section below.

If you want to learn more about growing blueberries, check out these articles next:

About Kristine Lofgren

Kristine Lofgren is a writer, photographer, reader, and gardening lover from outside Portland, Oregon. She was raised in the Utah desert, and made her way to the rainforests of the Pacific Northwest with her husband and two dogs in 2018. Her passion is focused these days on growing ornamental edibles, and foraging for food in the urban and suburban landscape.