[ad_1]

Peace lilies, Spathiphyllum spp. are easygoing houseplants that seldom suffer from disease issues when provided with the right care.

In fact, they are so easy to grow that Dr. Leonard Parry, Horticulture Professor at the University of Vermont says that they have been called the “perfect houseplant.”

In our guide to growing peace lilies, we cover how to cultivate these popular plants indoors.

For best results, they require a location that receives six to eight hours of bright, indirect sunlight, and well-draining soil.

Fertilizer applications once a month during the growing season, watering when the top inch of soil dries out, and occasional repotting is just about all that’s needed to keep them happy.

However, while it doesn’t happen often, these tropical foliage plants can sometimes fall prey to disease.

In this guide, we’ll cover the most common diseases that can affect peace lilies, and what you can do about them.

These diseases are primarily a problem when commercial growers have large-scale plantings of peace lilies to produce them for sale.

You should be able to avoid these issues by purchasing your peace lily from a reputable nursery, and inspecting it before you bring it home.

Select healthy specimens, and avoid those with yellow leaves, mold on the surface of the potting soil, and wilting foliage.

1. Cylindrocladium Root Rot

Cylindrocladium root rot is a fungal infection caused by Cylindrocladium spathiphylli.

Your houseplant can be vulnerable to this disease if it is overwatered, or is planted in soil that lacks adequate drainage.

In warm, moist conditions, this fungus can destroy the entire root system in the space of a few weeks to a few months.

It can be difficult to detect, because the rot can progress for several weeks before the peace lily shows any symptoms of infection on its leaves.

Typically, the first you’ll notice of this infection is the yellowing of the lower leaves, and possibly wilting foliage.

On closer examination, the leaves and petioles may also have dark brown spots, particularly on the lower portions of the petioles.

By the time you notice this discoloration, it’s likely that the roots are severely rotten, and you have little hope of saving your peace lily. Discard the plant and all the soil from the pot into the trash.

You’ll need to sterilize the pot if you wish to reuse it, as the fungus produces infectious resting structures called sclerotia that can survive in soil and organic matter.

2. Dasheen Mosaic Virus

This viral disease causes a mosaic pattern of yellow to light green to appear on new leaves of plants that are infected. It generally does not cause much, if any, reduction in growth or failure to thrive.

The virus is typically spread between plants by insects, such as aphids, infected potting soil, or gardening tools.

There is no cure for this virus, and while your peace lily may not show any ill effects, apart from discolored foliage, keep in mind that it can infect other related houseplants, such as anthurium, dieffenbachia, and philodendron.

3. Leaf Blight

Phytophthora nicotianae is a water mold (oomycete) that causes leaf blight on a large variety of plants. It is generally spread by splashing water. High moisture levels and humidity are ideal conditions for infection.

The primary symptoms of this disease are leaf margins and centers that have black or brown dead spots.

If conditions are moist, the spots may appear wet and mushy. However, if the foliage is dry, these spots may be dry.

As the disease progresses, the spots will expand into larger lesions.

The damaged tissue can also be colonized by secondary fungi that can change the appearance of the disease.

If you catch it in the early stages, you can try repotting your plant into a new, sterilized container, using fresh sterile potting soil.

Cut off the damaged foliage and dispose of it in the trash, as the spores can persist in plant debris. Also dispose of all old potting soil and be sure to sterilize the container if you intend to reuse it.

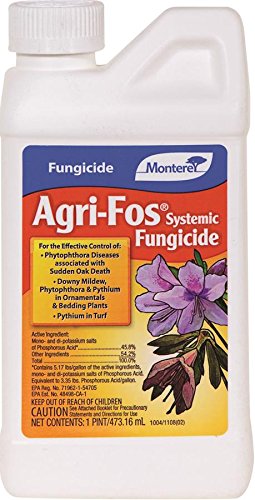

A soil drench with Monterey Agri-Fos Disease Control Fungicide, available via Amazon, can be applied immediately after repotting, according to package instructions.

Monterey Agri-Fos Disease Control Fungicide

Watering at the base of the plant and keeping the foliage dry can help to prevent this pathogen from taking root (or leaf in this case).

4. Pythium Root Rot

Pythium root rot is caused by another water mold, Pythium spp. The leaves of plants infected with this water mold usually appear yellowish and wilted.

By the time you notice the symptoms on the foliage, the roots will be black and mushy.

This disease can be difficult to distinguish from Cylindrocladium root rot, the most notable difference being that in the case of Pythium root rot, the petioles are typically not affected.

Damp conditions favor the development of this disease, so avoid overwatering, water at the soil level, and make sure your plant has well-draining potting soil.

Early-stage treatment is the same as that for Cylindrocladium root rot: repotting into fresh potting mix, and a soil drench using Monterey Agri-Fos Disease Control Fungicide.

However, if your peace lily is severely infected, you are best served starting over with a new plant. Remember to dispose of all infected potting soil and plant debris in the trash.

You May Never Encounter These Diseases

As mentioned, most of these diseases have their origin in commercial nurseries where large numbers of plants are grown and propagated in close proximity.

Although I will admit that I did lose a peace lily to root rot, odds are good that you can grow your Spathiphyllum plants unscathed.

By keeping the foliage dry, watering only when the top inch of soil is dry, and providing your plants with adequate light, you will likely never have to contend with any of these diseases.

Have you struggled with a disease on your peace lily? If so, let us know in the comments section below.

And for more information on growing peace lilies, check out these guides next:

© Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock. With additional writing and editing by Clare Groom.

About Helga George, PhD

One of Helga George’s greatest childhood joys was reading about rare and greenhouse plants that would not grow in Delaware. Now that she lives near Santa Barbara, California, she is delighted that many of these grow right outside! Fascinated by the childhood discovery that plants make chemicals to defend themselves, Helga embarked on further academic study and obtained two degrees, studying plant diseases as a plant pathology major. She holds a BS in agriculture from Cornell University, and an MS from the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Helga then returned to Cornell to obtain a PhD, studying one of the model systems of plant defense. She transitioned to full-time writing in 2009.

[ad_2]

Source link

+ Planting String of Watermelon Succulents

+ Planting String of Watermelon Succulents  with Garden Answer

with Garden Answer