Contracting a disease called “black death” is almost certainly bad news.

Fortunately, in this article we will not be discussing the bubonic plague, but instead a relatively new and lethal viral disease that affects hellebore flowers.

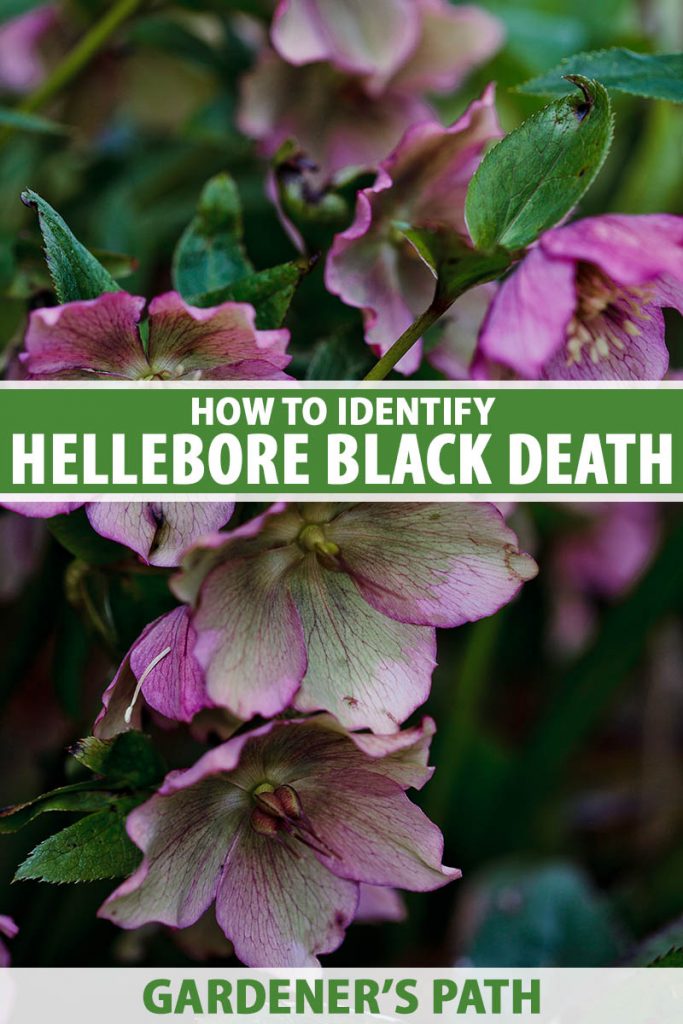

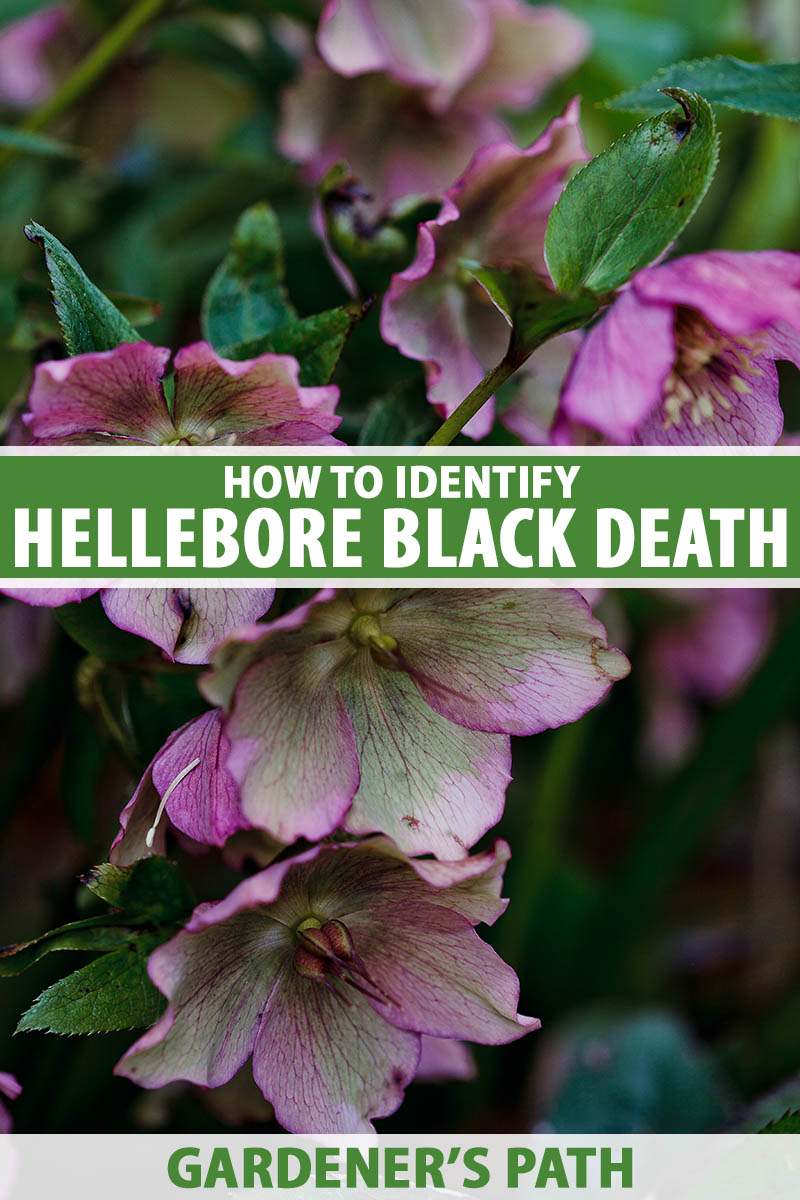

Hellebores are herbaceous perennials, loved for their winter blooms that pop up in January or February and last until early spring.

In ideal conditions, they are typically easy to care for and will return year after year to provide color in the bleak winter landscape.

Hellebore black death is a devastating viral disease that affects some hellebore species more than others.

Species and cultivars of Helleborus orientalis and H. x hybridus are the most vulnerable, and H. argutifolius and H. niger appear to be less susceptible.

Thankfully, this viral infection is fairly uncommon in home gardens.

While there is no cure, in this guide we’ll cover how to identify the symptoms of this fatal disease.

Recent Discovery of Black Death

Symptoms of this disease were first reported in continental Europe and the United Kingdom in the early 1990s.

Over time, it has spread to the US, New Zealand, and Japan probably via infected nursery stock.

In the US, symptoms matching those of hellebore black death were first observed in a plant nursery in Washington State in 2000.

According to an article published in the journal Plant Disease, in 2009 scientists identified the cause of the symptoms commonly called “black death” as a new viral disease affecting hellebores, and named it the Helleborus net necrosis virus, or HeNNV for short.

HeNNV is classified as a Carlavirus, one of a number of species of plant viruses, typically spread by aphids, whiteflies, and infected gardening tools or machinery.

Several other viruses are known to cause disease in hellebores, including mosaic virus, Chrysanthemum virus B, Tomato spotted wilt virus, and Cucumber mosaic virus, but none are as devastating as HeNNV.

And none of them have been associated with the specific symptoms of black death.

Symptoms

Older plants are most likely to show symptoms, typically on newly emerging foliage and flowers.

The most striking appearance of this disease is black streaks on the surface of the leaves and on the main stem of the plant that is infected.

Additional symptoms can include:

- Black streaks on flower bracts

- Ring spots on petioles and bracts

- Brittle, severely stunted brown to black new growth

- Blackened leaf veins

In the early stages of infection, symptoms may appear to be similar to other, treatable, diseases such as botrytis leaf spot (Botrytis cinerea) and fungal black spot (Microspaeropis hellebore).

While both black death and fungal black spot cause – you guessed it – dark spots on the leaves, in the case of black death they tend to follow the veins, and appear as streaks rather than blotches.

Typically, symptoms will become worse over the course of a few weeks, growth will be stunted, and the plant will eventually die.

Plants may be infected with this virus for up to 18 months before they start showing symptoms, but once symptoms are visible, the plant will not recover.

It is this long period of time when the plant may be carrying the virus, but appearing asymptomatic, that has contributed to its spread.

How to Limit Its Spread

HeNNV is not known to infect plants other than hellebores, so you don’t need to worry about it spreading to edible crops or other ornamentals in your garden.

According to the Royal Horticultural Society, the hellebore aphid Macrosiphum hellebori has been identified as a possible vector for the HeNNV virus.

Aphids and whiteflies are common vectors for other plant viruses, spreading disease by feeding on the sap of infected plants and transmitting it to healthy specimens.

You can learn more about how to control aphids in our guide.

If you identify a plant that is likely suffering from this disease, you need to dig it up and remove it immediately, bag it up, and dispose of it in the trash, do not place it on your compost pile.

You will not know whether your other plants are infected until they start showing symptoms, so you can choose whether to leave asymptomatic plants in the ground, or to purge them as well, to ensure that the virus is eliminated.

Good gardening practices, such as disinfecting your pruning shears and other tools in between each use can help to prevent the spread of viruses and other pathogens.

A Dark, Deadly Virus

The only bright side in this story is that this disease is relatively rare in home gardens compared to nurseries and large plantings in display gardens.

Since it is highly contagious and there is no cure, you will have to ruthlessly cull any infected plants, and place them in the trash.

Have you encountered hellebore black death? Let us know in the comments section below.

And for more information about growing hellebores in your garden, check out these guides next:

© Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock. With additional writing and editing by Clare Groom.

About Helga George, PhD

One of Helga George’s greatest childhood joys was reading about rare and greenhouse plants that would not grow in Delaware. Now that she lives near Santa Barbara, California, she is delighted that many of these grow right outside! Fascinated by the childhood discovery that plants make chemicals to defend themselves, Helga embarked on further academic study and obtained two degrees, studying plant diseases as a plant pathology major. She holds a BS in agriculture from Cornell University, and an MS from the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Helga then returned to Cornell to obtain a PhD, studying one of the model systems of plant defense. She transitioned to full-time writing in 2009.