[ad_1]

Meloidogyne spp.

Root-knot nematodes (RKNs) truly are a menace. There are over 100 species in the Meloidogyne genus found worldwide, and they can affect almost every type of plant.

And the worst part about it is that you might not even know that your plants are infested until it is too late to save them.

Symptoms usually start with a general decline in the health of the plant, with signs of stunted growth, wilting, or yellowing of the leaves.

Commercial farms often preemptively treat their soil with fumigants. However, these compounds are biocides – they kill all forms of life, including beneficial nematodes, soil microbes, and earthworms.

This is not something you want to mess with in your home garden. And even if you wanted to, it’s illegal to do so without proper training, licensing, and equipment.

Fortunately there are viable and safe options available to the home gardener to fend off an attack, including a number of organic methods that we will discuss in this article.

Here’s what I’ll cover:

What Is a Nematode?

Nematodes are microscopic, elongated worm-like organisms that live in soil, under water, or in the tissue of the plants or animals that they parasitize.

If you are used to battling them in your garden, you may feel like the only good nematode is a dead nematode. However, if you look at the big picture, estimates suggest there are over half a million species, and only about 10 percent of them parasitize plants.

Most nematodes are considered beneficial. Many species consume bacteria and fungi in the soil, and release nutrients from these organisms, enriching the soil.

Some are even used as biological controls.

These organisms thrive in warm climates, and the parasitic species are a particular problem in tropical and subtropical areas. Nematodes in the southern US can have 10 reproductive cycles a year, so their numbers can increase rapidly.

They are typically a problem in the summer as root-knot nematodes are unable to enter the roots at temperatures below 64°F, which is good news for your cool-weather crops.

Root-knot nematodes create wounds on the roots that can be used as entry points by harmful fungi and bacteria. In many cases, these secondary infections can do more damage than the root-knot nematodes themselves.

Symptoms of Root-Knot Nematode Infestation

It helps to understand how these particular nematodes cause symptoms.

As far as pests go, RKNs are couch potatoes – and are referred to scientifically as sedentary nematodes. Once they enter the root of a plant and find a feeding site, they typically stay where they are.

Parts of them may stick out of the root, but that’s as far as they go.

When they infest a root, the females lose their worm-like shape. In fact, the name of the genus, Meloidogyne, is derived from the Greek word for “apple-shaped female.”

They can lay up to 500 eggs at a time, and the egg mass remains attached to their bodies, giving them a rounded shape. When examined under a microscope, these masses look like tiny golden brown dots.

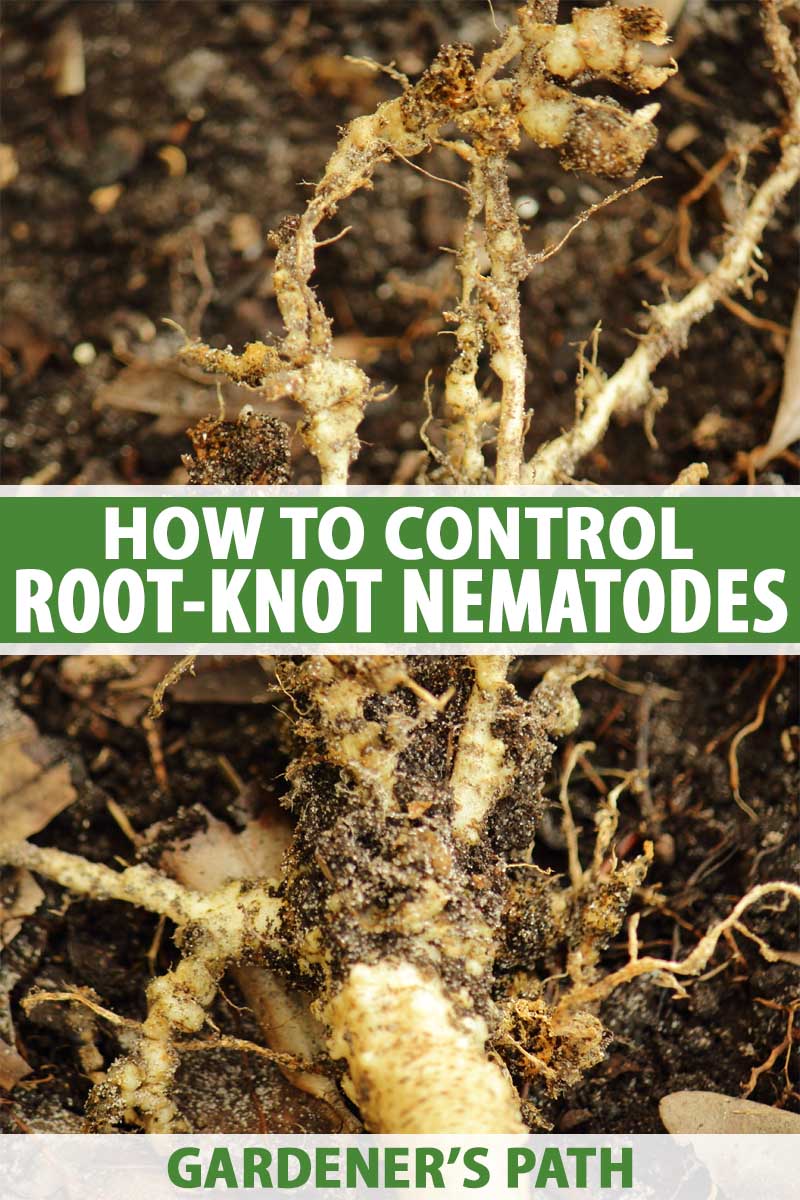

The females burrow into the root and feed on the root tissue of the infested plant. As a result of this feeding, the roots swell into large galls, typically between one and 20 millimeters across. When the eggs hatch, the juveniles also start feeding on the root tissue, increasing the damage.

This root damage can adversely affect the plants’ ability to take up water and nutrients from the soil.

Diagnosing an infestation can be tricky. These pests don’t produce specific symptoms in the visible portions of the plant. When you inspect your plant, there is no particular symptom that screams “I am a nematode infection.”

Symptoms that your plants may exhibit if they are suffering from a root-knot nematode infestation include wilting, chlorosis, yellowing, stunted growth, and even death of the plant.

This can make it difficult to diagnose a root-knot nematode infestation because you may notice your plants wilting on a hot day, and simply assume they need more water. But the problem may not be lack of irrigation, but the plants’ inability to absorb the available moisture.

In a similar vein, if your plants are showing signs of nutrient deficiency in the form of yellowing or discolored foliage, you may attempt to remedy the issue by applying fertilizer. In the case of a RKN infestation, this will have no effect.

Typically, it won’t just be one plant that is suffering. As mentioned, these pests don’t travel very far, so you may find that plants in one section of your garden seem to be thriving while those in another location are struggling. This could be a vital clue in your attempt to diagnose root-knot nematode issues.

If additional irrigation or fertilization fails to revive your plants, you can pull one up and inspect the roots. If you find the roots have swollen nodules – galls – and are showing signs of decay, it is likely that your garden is infested with these pests.

However, you need to be careful not to confuse galls caused by RKNs with the nodules that nitrogen-fixing bacteria produce in legumes, such as peas and beans.

These swellings are easily distinguished from root-knot galls by how they are attached to the root:

- The nodules on the roots of leguminous plants are loosely attached, and if they are pierced will contain a milky pinkish-brown liquid inside.

- The root-knot galls are an integral part of the root, are firmer, and typically measure between one and 20 millimeters across.

If after inspecting the roots you are still unsure, you may wish to obtain a professional diagnosis of your infested plants. Your local county or state Cooperative Extension Service will be able to recommend commercial labs that identify nematodes.

To take a sample, dig about a quart of soil from the site where you dug up the diseased plant and put the soil and the plant in a plastic bag.

Do not let the bag sit in the sun for any amount of time because it will cook the nematodes, and make them impossible to identify. I’ll discuss more about this later.

Prevention and Control

As mentioned, these lazy nematodes spread quite slowly if they are left to their own devices. They’ll happily take up residence in your plants’ roots and gradually spread to and devour those in the immediate vicinity.

However, they can be easily spread around your yard on infected plant material, soil, gardening tools, and even on muddy footwear. If you catch an infestation early enough, you can take steps to prevent the spread to other areas of your garden.

In addition to attacking your crops and ornamental plants, RKNs thrive and reproduce on many types of common weed. You may not even notice that your weeds are infested until the nematodes have multiplied and started spreading to nearby crops.

This is one of many reasons why keeping weeds under control is always good gardening practice.

Unfortunately, once a root is infected with RKNs, there is no way to kill the pest without killing the plant. But there are measures you can take in your garden to prevent them from taking up residence in the first place – or returning to devour next season’s crops.

Healthy soil with plenty of organic matter will encourage the growth of beneficial nematodes, bacteria, and fungi that can help to reduce infestations. In addition, the healthier the plant, the higher the likelihood that your crops may thrive and produce a harvest even in the presence of this pest.

Rotating your crops is always good gardening practice, and in this case it can be beneficial, as some Meloidogyne species are selective in their choice of host plants.

Control and prevention of these pests goes hand in hand. Unlike some plant diseases, it’s not possible to simply apply a single product and see immediate results. Treatment of an existing infestation involves reducing the numbers of RKNs present in the soil and then rebuilding the soil with beneficial microbes that can provide a level of biological control.

Plant Resistant Varieties

Resistant varieties are available for many common garden crops. If you have a known issue with RKNs in your garden, you may wish to select varieties that are resistant.

Look for a label on your seed packet that says VFN. This indicates the variety has some resistance to Verticillium wilt, Fusarium wilt, and nematodes.

However, you need to keep in mind that resistance is not the same as immunity. Even though a variety may be listed as resistant to RKN, in hot weather – typically around 82°F – when the nematodes are very active, they may still take hold and damage your crops.

Planting resistant varieties is a good strategy if you have already taken steps to prevent an infestation.

Fallow Part of an Infested Garden

Fallowing is the practice of leaving a plot with no plants in it for a prolonged period of time to starve the nematodes or other pests. With no host plants, the nematodes will die off, as they can only travel short distances.

If you have a large garden, you can fallow part of it each year to purge the RKNs. But it’s not as simple as set-and-forget: you’ll need to till the soil regularly to remove weeds and to bring the RKNs to the surface where they will dehydrate and die.

Additionally, for those with smaller yards this isn’t a very efficient use of productive garden space.

Cover Croping

There are a number of plants that may help to reduce the populations of these roundworms in the soil. Instead of leaving parts of your garden fallow, you could consider cover-cropping with marigolds or canola.

Stephen Vann, TL Kirkpatrick and Rick Cartwright, plant pathologists at the University of Arkansas Extension Service recommend planting specific varieties of marigold to repel these pests.

They recommend the French marigold cultivars ‘Petite Gold,’ ‘Petite Harmony,’ or ‘Tangerine.’ These cultivars release a compound into the soil that is toxic to RKNs.

However, not all marigolds are will work: they strongly advise against planting ‘Tangerine Gem’or hybrid marigolds, which can actually increase the populations of harmful nematodes.

The marigolds should be planted in seven-inch rows, with plants spaced seven inches apart. This configuration makes it easy to weed between the flowers, which is important, since weeds can harbor RKNs.

Plow the marigolds into the soil after they have grown for at least two months.

Two varieties of canola, ‘Humus’ and ‘Dwarf Essex,’ contain high levels of a natural nematicide.

In warm climates, plant the canola in the fall and allow it to grow through the winter. In cooler climates, plant as soon as the ground thaws in spring, after all risk of frost has passed.

Plow the plants into the soil in mid- to late summer and allow them to decompose for about a month before you plant crops in your garden.

Solarize Part of Your Garden

You probably thought I was joking about following up on cooking RKN populations in the sun. However, you can harness their sensitivity to heat to your advantage.

Solarizing involves thoroughly irrigating the soil and then putting down sheets of clear plastic to let the sun heat up the soil and cook the nematodes.

To do this, till the moist soil first, then put down a sheet of two- to four-millimeter-thick clear plastic. Weigh down the ends with soil or bricks to prevent it from blowing away.

Leave the plastic in place for at least two months during the summer. Carefully remove the plastic and plant your fall crop without tilling, as this could bring RKNs and weed seeds into the solarized layer.

This technique will be effective against nematodes in the top 12 inches of the soil and you need to keep in mind that there may still be some lurking deeper down.

Apply Chitin

You can also introduce materials like the crushed shells of crabs and shrimp, which contain chitin, by digging them into the soil.

Chitin helps to increase populations of beneficial soil microbes that feed on root-knot nematodes and provides a level of biological control.

Neptune’s Harvest Crab & Lobster Shell 5-3-0

Neptune’s Harvest is a natural fertilizer 5-3-0 (NPK) that will add nitrogen and phosphorus to the soil as well as chitins. Keep in mind that it doesn’t contain any potassium so you may need to apply it in conjunction with a high-potassium fertilizer.

You can find Neptune’s Harvest Crab and Lobster Shell available from Arbico Organics.

Organic Nematicide

You can also use an organic nematicide such as Monterey Nematode Control, which is made from the saponins extracted from the soapbark tree, Quillaja saponaria.

When applied in the spring, it limits the development of young pests. Repeated applications may be necessary, according to package instructions.

Keep in mind that although this product is formulated to parasitic nematodes, it can also affect the beneficial ones as well.

Monterey Nematode Control

You can find quart-size bottles of Monterey Nematode Control available at Arbico Organics.

Biocontrol Agents

It seems fitting to control RKNs with another type of nematode.

NemAttack™ SR

The species Steinernema riobravis has been reported to control RKNs by attacking the eggs and preventing them from hatching.

It is available from Arbico Organics as NemAttack™ SR.

Multiple Ways to Control Root-Knot Nematodes

While you won’t be able to save a plant that is already infested, there are a number of measures you can take to stop the spread of RKNs in your soil.

These range from solarizing parts of your garden to applying beneficial nematodes.

A healthy soil community will increase the number of microbes in the soil that naturally keep the populations of these organisms in check.

Have you had a problem with root-knot nematodes in your garden? Let us know in the comments section below!

Read on to learn more about improving the health of your soil to help keep pests and disease in check:

© Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Product photos via Ocean Crests Seafood and Arbico Organics. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock. With additional writing and editing by Clare Groom.

About Helga George, PhD

One of Helga George’s greatest childhood joys was reading about rare and greenhouse plants that would not grow in Delaware. Now that she lives near Santa Barbara, California, she is delighted that many of these grow right outside! Fascinated by the childhood discovery that plants make chemicals to defend themselves, Helga embarked on further academic study and obtained two degrees, studying plant diseases as a plant pathology major. She holds a BS in agriculture from Cornell University, and an MS from the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Helga then returned to Cornell to obtain a PhD, studying one of the model systems of plant defense. She transitioned to full-time writing in 2009.

[ad_2]

Source link

+ Planting String of Watermelon Succulents

+ Planting String of Watermelon Succulents  with Garden Answer

with Garden Answer