[ad_1]

How rumours almost became architectural history

Early 20th century Melbourne architect Howard Ratcliff Lawson was larger than life—a prolific designer with more than 200 buildings to his name who held court with judges and ministers, discussing his progressive ideas for urban planning and social housing.

But Lawson has gently slipped through the cracks of architectural history. He is largely a forgotten architect, apart from being known as the genius mind behind South Yarra’s astonishing Beverley Hills flats complex. And, in that genre of forgotten Australian architectural history, in the murky depths of vaguely remembered detail, his story has become muddied. Rumours and myths about him circulated for decades after his death, intensifying and becoming more fantastical with each retelling. Though held in high regard during his lifetime, his architecture was posthumously devalued, partly through the prism of stories that had become ‘facts’ in populist culture, and partly through a lack of either alternate information or extensive academic study to explain his design intent. The enormous tally of his works has also faded from history’s pages, to the point where he is now generally only known for his 1930s works, and, of those, Beverley Hills and Garden of the Moon (Arthurs Seat), are the works with which he is mostly associated.

Lawson recycled many elements of earlier building fabrics in his landmark Beverley Hills flats (c. 1935–1936). The stunning leadlight and stained glass window in an apartment in Block 2 is believed to have come from one, or more, of the nineteenth-century mansions of Toorak that were demolished in the early 1930s. This area was originally the cafe and small shop for the complex, but has since been converted into an apartment.

Image:

Personal photo supplied to the author by Heather Nette-King

Lawson’s reputation and name has been tarnished over time as a consequence of two main rumours: first, that he was not really an architect, yet called himself one; second, that he was a ‘cheapskate’ who used recycled materials to save costs. His later architecture, in particular, is very different to that of his contemporaries. There has been confusion over how best to define and label his works, partly due to a lack of understanding of who Lawson actually was and what drove his architectural mind. Delving into the archives of history clarifies not only what drove him and his insatiable appetite for design and construction, but also illuminates his life, putting to rest many of the rumours about him. In this article, I discuss and dispel the two main rumours.

The architect who builds: the tagline that came to define the rumour

It is frequently said that Lawson himself came up with the tagline ‘the architect who builds’ after he was refused registration as an architect. While this makes for a colourful story, and has been repeated in both published works1 and opinion pieces2 on social media platforms,3 it is a tangled explanation of the truth. It has also been suggested that Lawson only began property development (and using his famous ‘architect who builds’ tagline) after his registered architect application was refused.4 Rather than a flamboyant salesman who pretended to be what he was not, the archives show a different sequence of events that paints a very different picture.

Lawson enrolled in architecture and building construction studies at the Working Men’s College (now RMIT) in 1902, when he was 17 years old, and studied there for the next three years.5 Initially, he worked as a builder, and would only later work as an architect. His maternal uncle, Ernest Henry Ratcliff, was a director of the Glen Iris Brick and Tile Company, as well as a builder and investor.6 The young Lawson worked for his uncle as a building manager,7 and first garnered public attention for his role as the daring young builder of the Britannia Theatre in Bourke Street, Melbourne, in 1912.

Lawson gained welcome publicity for his progressive ideas of efficiency as the young building manager of the Britannia Theatre in 1912.

Image:

Unknown photographer and date, Britannia Theatre, Cinema Treasures

Recycling: pioneering Melbourne warehouse conversions

Hot on the heels of the great success of the Britannia Theatre, Lawson embarked on two even more ambitious projects in 1912, this time applying his skills in building efficiency to property development and working in his own employ. The bold scheme involved recycling an entire factory into completely new uses. While this is common today, and is considered architecturally clever as well as environmentally responsible, in early twentieth-century Melbourne, it was inspired.

The Hoadley family, known in Australia for their confectionary and chocolate manufacturing, were friends with Lawson. When the Hoadleys decided to sell their jam factory at Snowden Gardens near Princes Bridge, South Melbourne, in favour of new premises a little further out of the city, the large landholding set Lawson’s active imagination into top gear.

Hoadley jam factory, c. 1900, before conversion to a theatre and flats.

Image:

Robert Vere Scott, photographer, Looking south across Yarra River at Princes Bridge, Melbourne, c. 1890–1910, State Library of Victoria, Pictures Collection, H2006.48.

Abel Hoadley had wanted to sell the factory as a whole but, due to lack of interest, split it into two parts: south (which was to be leased) and north (which was to be sold). This gave Lawson the chance to get involved in both parts, but in different ways. Lawson purchased the northern portion for the sum of £14,000 in August 1912.13 Considering that he was only 27 years old and, at that stage, a building manager with architectural aspirations, it was an extraordinary sum of money.

Lawson planned to convert the factory into flats, and would fund the works, as well as recoup the original purchase price, via the raising of shares for a new company to oversee the process. This prospectus was advertised in Punch the following month.14 The choice of architect for the conversion was Robert Haddon, who had been head of architecture when Lawson studied at the Working Men’s College, a fact that no doubt influenced Lawson’s selection. Haddon was well known as being flexible in working with other Melbourne architects, and was held in high regard by the architectural profession.15

The prospectus makes it clear that Lawson’s own designing eye and hand were also at work: “The alterations, which are estimated to cost £5800, have been designed by Mr R. J. Haddon, the architect of the proposed Company, and by Mr Lawson.”16 The prospectus explained that the proposed Alexandra Mansions would be designed to include the very latest ideas in modern flat living, and would:

Comprise suites of rooms with all accessories complete, and also single rooms. Hot and cold water will be laid on to all bathrooms, the building will be lit by electric light, while every modern comfort in the way of ventilation, heaters, telephones, etc., will be installed, where necessary, throughout the buildings.17

The new flats were intended to provide short- and long-term accommodation for middle-class tenants, and were a response to the growing demand for flats as an alternative to boarding houses. Most flats in Melbourne at this time were either conversions from existing residential properties (i.e., mansions into flats) or were purpose-built on the land of former mansions.

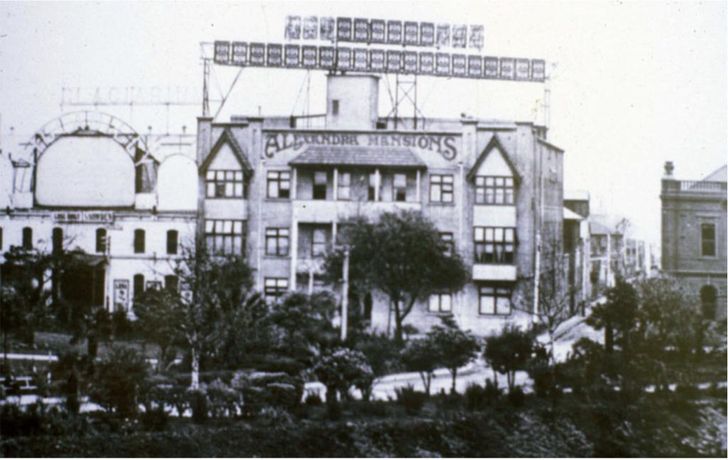

Alexandra Mansions was a very early example of adaptive building re-use, converting a former factory into upmarket flats, including a rooftop garden for residents’ use.

Image:

Unknown photographer, title and date, image courtesy of Professor Miles Lewis.

Solving the servant problem

Lawson believed that the Yarra River, then a dumping ground for the various factories that lined its banks, could be a desirable location.18 Signalling both this and his belief in the value of providing a more modern style of accommodation to respond to changing social conditions, the prospectus extolled the benefits of lifestyle for future residents:

These Mansions will be at the very door of the city, on the south side of Prince’s Bridge, facing eastward towards the panorama of the Alexandra Drive, the winding river, and the city beyond, and fronting immediately the picturesque slope of Snowden Gardens …

Residents in the Mansions will be so near the city that they may easily walk to any of its business centres within a few minutes, while every modern appliance and convenience to enable residents to enjoy life while minimising the ‘servant problem’ will be provided.19

The southern part of the Hoadley factory was also recycled into a totally new use, again with Lawson’s involvement. A new company, Snowden Pictures, leased this portion, with the intention of converting it into a silent picture theatre.20 ‘The alterations will be under the supervision of Mr Lawson, who has just completed the Britannia Theatre’, explained the prospectus.21 Lawson held financial interest in the project too, as he was also a director of the Snowden Picture company.22 One of his fellow directors was his friend, Walter Hoadley, son of Abel Hoadley.

Lawson’s expertise in swift and efficient building programs meant that the Snowden Picture Theatre was open by the end of October 1912, just three months after the prospectus was advertised. The architect credited for this work was A Phipps Coles, but it is difficult not to ponder how much influence Lawson would have imparted, given his later works and passion for new ideas. In any case, the theatre was applauded for its modern use of colourful, and moving, lighting on the facade, which was then a relatively unusual concept:

The Snowden Picture Theatre, with vari-coloured disappearing electric lights illuminating its entrance at Prince’s bridge, was formally opened last evening … The theatre is replete with the most modern fittings. There is a nursery with bassinets for infants, left in charge of the nurse, a smokers’ gallery, screened off with plate glass, at the rear of the dress circle, from which there is an uninterrupted view of the picture screen; and refreshments nooks, where ices and other delicacies can be enjoyed without any of the programme being missed. Special attention has been paid to the ventilation, and with the electric fans.23

Both buildings were later demolished. Today the site is part of Melbourne’s greater arts precinct and the National Gallery of Victoria, Southbank.

Importantly, the conversion of a factory into flats and a picture theatre foreshadowed Lawson’s life-long interest in recycling building materials, and goes towards an understanding of his beliefs in efficiency.

Howard Lawson vs the Architects Registration Board of Victoria

Until the Architects Registration Act amendment was passed in 1939, use of the title ‘registered architect’ was not restricted. Lawson was perfectly entitled to call himself an architect at this time, before formal registration necessitated that rules must be followed.

In 1922, the Victorian Parliament passed the Architects Registration Act, which decreed that a newly formed Architects Registration Board of Victoria would have the power to create a register of members, and could ‘issue or cancel certificates of registration’.31 This Act also limited the use of the title ‘registered architect’ to members who had been admitted to the board’s register. The board could chose to admit members on several grounds. For example, an applicant who did not hold formal qualifications, but had ‘for a period of at least one year before the first day of January One thousand nine hundred and twenty-three [sic] been bonâ fide engaged in Victoria in the practice of the profession of an architect and … made application for registration within six months after that date’ could be admitted.32

It was under this option that Lawson chose to apply in 1923. For reasons unknown, he did not mention his earlier study of architecture at the Working Men’s College, but instead stated: “I have been 12 years engaged in Victoria in practice as an Architect”.33 The exchange that followed between Lawson and the Architects Registration Board tells a more detailed story, and can be found in the original file of application held at Public Record Office Victoria.34

The board requested a meeting with Lawson to discuss his application. While there are no details of what was discussed, it seems that Lawson provided examples of his works that involved both design and construction, as the board subsequently, and very subtly, suggested that he would do better to supply a list of buildings that he had designed only—not designed and built.

The letter noted that: “The Board does not regard the mixed practice of designing buildings and carrying out Building operations as bona fide practice of the profession of an Architect.”35 If Lawson had carefully read between the lines, he would have realised that he was being given another chance. Lawson could easily have produced a list of buildings that satisfied the board’s delicately worded request, as evidenced in his later court documents. But he did not do this, instead choosing to respond with firm resolve and admonition of the board’s point of view. He instructed his solicitors to prepare and send a letter detailing a very long list of buildings that he had proudly designed and built, as well as enclosing several glowing letters from his clients. An excerpt provides insight into Lawson’s determination:

Attention to this matter has been delayed owing to the holiday season; but we now enclose a list of buildings designed by Mr. H. R. Lawson and built by his Company under his supervision. We submit [that] your Board’s previous decision was wrong and that on the evidence before it our Client’s application should have been granted. However, we tender this further evidence in compliance with your Board’s wish, and confidently expect that our client will experience no further trouble in obtaining registration.36

However, the exchanges between the board and Lawson’s solicitors moved further and further from resolution, and dragged on for some months as neither side would budge. A terse letter from Lawson’s solicitors to the board in February 1924 expressed Lawson’s sense of righteous indignation: in addition to threatening legal action, it asserted that the board was “not entitled to put its own narrow interpretation on the words ‘the practice of the profession of an Architect.’”37

Not surprisingly, after receiving the letter the board decided to end the matter with a final decision addressed directly to Lawson. To reinforce that the matter was concluded, they returned his application fee.

Lawson’s decision to fight rather than conform created the basis of a later-muddled story that reversed the sequence of true events, and led to a rumour about his claim to be an architect.

Ironically, the majority of the vast number of designs – more than 200 –that Lawson produced, including Beverley Hills and Garden of the Moon, were created prior to the end of 1939, so were well within the timeframe in which he was legitimately allowed to call himself an architect. Thus, the rumour about him falsely claiming this title is incorrect.

The reality is that Lawson simply got caught in the crosswires of an evolving definition of what constituted the profession of a registered architect in the early twentieth century, as the industry tried to position itself in a changing world. It is clear that Lawson both understood, and applied, the principles of architectural design. The extant examples of his works, such as Beverley Hills, are testament to this.

World War II curtailed building activities across Australia, restricting works between 1939 and 1945 for most architects and builders. After the war ended, Lawson was looking forward to resuming his business, but such plans came to abrupt end when he died in January 1946.

Lawson left behind a legacy of extraordinarily imaginative buildings. He used recycled materials in his buildings not because he was a ‘cheapskate’, as so many have falsely alleged, but because he had a passion for efficiency and an appreciation of the inherent value of beautiful things. His use of recycled products was decades ahead of his time. Whether that meant recycling a factory into a new style of residential housing, like Alexandra Mansions, or celebrating the beauty of a nineteenth-century leadlight window in the 1935–1936 Beverley Hills flats, Lawson was never afraid to follow his own convictions.

Held in high esteem during his lifetime, the rumours that damaged his reputation were posthumous, and may, in part, have circulated due to changing ideas about what was considered desirable in the pursuit of contemporary architecture post–World War II. An emphasis on new materials and simplicity of form meant that recycling was not valued. Further, the use of decorative elements was no longer seen as playful or whimsical, but as an affront to the streamlined ‘honesty’ of postwar architecture. Indeed, during the mid-twentieth century, the architectural establishment eschewed ‘playful’ architecture as old-fashioned. The good and the bad were thrown together and relegated to history. In so doing, Lawson’s architecture was devalued and his use of recycled elements misunderstood. Somewhat ironically, our current awareness of the need to preserve and value existing materials in a world that is looking for new methods for sustainability have made Lawson’s ideas on recycling suddenly appealing.

The origin of the rumours and myths about both Lawson and his architecture are hard to pinpoint. Left unchallenged, what is certain is that, over the decades, they grew more colourful and exaggerated, taking on fantastical proportions. These popular stories were repeated in detail, so that, over time, they became accepted facts. Lawson was perceived as something of a scoundrel, an element that makes for a great story. From real estate copy to social media platforms, the story has run unfettered.

If the true measure of successful architecture is the ability to hold value independent of its creator, then Howard Lawson’s architectural legacy is quite safe. His rampaging imagination was not constrained by existing frameworks. He dreamed and built ideas that embody the power of architecture to transform the everyday into a world of whimsical imagination and beauty. Truly, that is his, and our, architectural and social heritage legacy, and no rumours or myths can dispel it.

This is an edited extract of the article “Howard R Lawson: the architect who built,” first published in Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 18, 2020. Read the original article here.

[ad_2]

Source link