[ad_1]

What intrigues us so much about the miniature? In one respect it offers little more information, if any, than its full-scale subject. Yet the singular act of shrinking the familiar forces our attention onto the very aspects of our built environment that we tend to otherwise overlook or, in some cases, choose to outright avoid. It is these conditions of the anonymous urban background that are the focus of Joshua Smith’s work. Initially a stencil artist, Adelaide-based Smith began his transition to miniaturist four years ago. His first foray into this distinctly three-dimensional form-making was a work that could act as a scaffold for stencilling: an urban backdrop in miniature form. The experiment was successful enough to spark the idea that in this background material lay the potential for a new focus for the artist’s work.

Perhaps the two most compelling aspects of Smith’s miniatures, at least from the perspective of an amateur viewer such as myself, are their exactitude coupled with their avoidance of romanticism. There is an exquisite hyperrealism apparent in the damaged storefront signage of Globe Slicers in New York City’s Bowery neighbourhood, and of its long-since-dialled telephone number on the awning and the patched letterbox in the door. When did the owners stop receiving mail? We can imagine the store being established in 1947 with an enthusiasm that lasted long enough for the date to be added over the tagged door some years later – and with a great deal of pride long departed. The shopfront’s shutters are well-locked, yet something is slightly amiss according to the stray lock laying on the rubber mat on the footpath. But perhaps the undamaged and appropriately positioned mat is itself a sign of life: that behind the shutters the shop survives, and a different life is evident once the shutters go up and the lights go on.

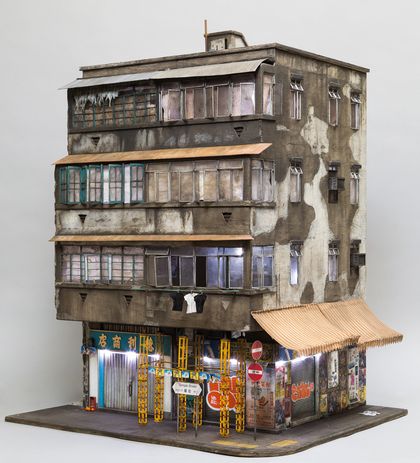

23 Temple Street is based on a building in Kowloon, Hong Kong, and is made from cardboard, MDF, plastic card, spray paint and wire.

Image:

Andrew Beveridge

Whether or not a truth exists in this narrative is irrelevant. The significance of the miniature lies in the fact that Smith has done the looking for us. In selecting the scene, determining its frame and focus and bringing the familiar forward, we can imagine our own stories of the people on either side of the facade. When asked about the importance of recording and expressing the imperfection of the city, Smith says, “The urban decay, grit and grime is what makes a building for me. It’s what I take the most inspiration from and really tells a story about the history of not only the buildings, but also of the people and the environment it is in. It’s my aim with each work to recreate this as accurately and realistically as possible.”

For the most part, the work is literal, with only minor artistic licence used for aesthetic purposes, and with ongoing materials and methods experimentation in each new piece. An enticing building is found, reference photographs taken, and the building broken down into segments of decreasing scale from walls, windows and facade elements to the footpath and its various urban accessories. After final painting, elements as exacting as discarded chewing gum are added, along with street items such as garbage bags and loose rubbish.

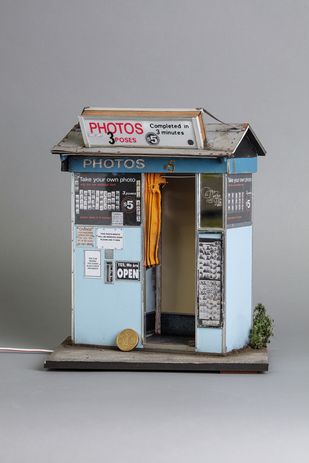

Chapel Street Photobooth is based on the iconic photo booth located in Melbourne’s South Yarra.

Image:

Andrew Beveridge

To finish, the miniature is photographed, and it is this process that gives it a significant second life. Beyond enabling the work to be experienced by a much wider audience than the miniatures themselves can reach through exhibition, the photographic shifting of viewpoint, focus and scale provides an even greater intimacy with the scene than is possible with the naked eye. Where the original work is remarkable in the flesh, its Instagram experience, which Smith curates with great effect, is a delightful open-source exhibition of a craft seemingly tailor-made to be held in our hands.

There is comfort in the familiar, even when it is presented in its most raw and unloved form. When the weed is as significant as the window detail and the advertising signage as communicative as the tag, we are left with not only an admiration for the meticulous crafting of Smith’s miniatures, but with gratitude for its gift of intimate urban interpretation.

[ad_2]

Source link