[ad_1]

Nerium oleander

We all have that friend who is perfect in many ways, but conversations about them always end with, “But….”

Nerium oleander is like that. It has many wonderful traits, the kind you would seek in a friend. It’s an evergreen – always there for you – and needs almost no maintenance (never clingy!).

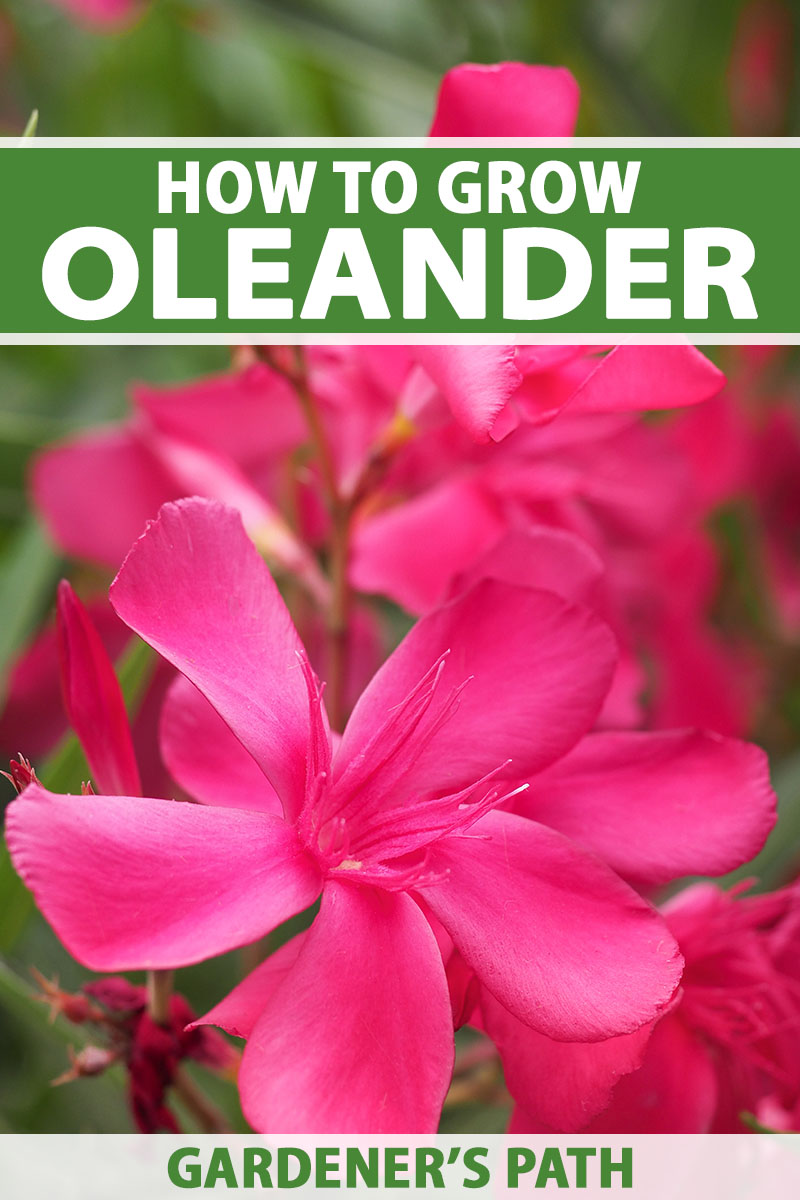

It’s upbeat and peppy, with vibrant flowers that bloom for months. They may be white, pink, red, salmon, light orange, or even a shade of light purple.

Most important, this shrub buddy is there when times get tough. In warm climates, it can survive and thrive despite various challenges, from blistering heat to drought and high humidity.

But… This garden shrub does have one negative characteristic, and it could be the end to a beautiful friendship.

Oleanders are highly toxic. If kids, adults, or pets eat the blooms, leaves, stems, roots, or dry debris, they may react with cardiac failure, cardiac arrest, or convulsions. Sometimes, these reactions are fatal.

If you are able to assure that humans or animals won’t accidentally ingest your oleander, though, I can’t recommend this vibrant, easy-care flowering plant enough.

It’s especially rewarding for those contending with hot summer temperatures.

And I’m here (hey, I’m a good friend, too!) to guide you through the growing process. Here’s what I’ll cover:

What Is Oleander?

Of North African and Mediterranean origins, the evergreen flowering shrub known as oleander grows worldwide in warm, subtropical regions. It’s a member of the Apocynaceae aka dogbane family.

Homeowners, communities, and transportation departments plant them because they grow quickly as reliable windbreaks and easy-to-care-for highway median adornments that deer won’t eat.

The thick leaves are shaped like sword blades. They form opposite pairs or are arrayed in whorls of three. The deeply-lobed flowers can be double or single, and bloom at the end of the branches, which can be spreading or erect.

There is also a relative with a similar name that is widely grown as an ornamental. I’ll only mention yellow oleander (Cascabela thevetia) in passing, because it’s a different species from the same family.

C. thevetia is also a poisonous plant to be aware of, and it’s native in Mexico and throughout Central America. Called “lucky nut” in the West Indies, it is nevertheless highly toxic and can cause fatalities too if ingested.

Getting back to Nerium, you can also recognize it because the seeds are downy. These are produced in a capsule that’s two to nine inches long, and splits open at maturity.

This species is available in three sizes.

Dwarf types grow from four to seven feet tall, and can spread a few feet. They’re a good size to grow in containers, which comes in handy in zones outside their range, and they’re also a nice option for groundcover or small shrubbery (grown far away from pets or small kids, though).

The midsize options grow to mature heights of eight to 10 feet, and tall types can reach anywhere from 10 to 25 feet. They’re popular for privacy screens or hedges, or pruned to present more like a tree with a single “trunk” stem.

The latter option looks really cool, but keep in mind that it’s not as low maintenance as planting in a sunny corner of your growing space and letting it take care of itself.

In the US, this flowering shrub is popular with gardeners on the West Coast, in southern states including Texas and Florida, and in many mild-temperature coastal regions, due to its tolerance of salt spray and ability to adapt to various poor soils and pH levels.

According to Elizabeth Head of the International Oleander Society (IOS), their namesake plant “can grow in an altitude of 100 meters near the Dead Sea to about 2,500 meters in the Atlas Mountains of North Africa.”

Though you can’t grow oleander outdoors year-round except in USDA Hardiness Zones 8-10, it is possible to grow them mostly outdoors in Zones 4-7, bringing them indoors for the coldest part of the winter.

Cultivation and History

Its toxicity may be the reason oleander has survived so long in the natural world, but surely its longevity as a prized ornamental is due to those glorious blooms.

And this plant has been around since ancient times, immortalized in the Roman wall paintings at Pompeii.

Head of the IOS also offers tidbits about the origins of its namesake shrub, saying “Ancient Greeks maintained holy forests of oleanders and garnished altars with their blossoms to honor the Nereides, who were considered to be infallible guides.”

More recently, Head adds, “in the 12th century, the oleander was one of the flowering shrubs together with the myrtle and the rose used by Arab gardeners of the Dar-al-Islam.”

This toxic beauty also plays a part in Galveston’s own island city history. Joseph Osterman, a merchant and financier who originally hailed from Amsterdam, brought tubs of double pink and single white varieties from Jamaica to Galveston in the early 1840s.

The flowering shrubs arrived on Osterman’s schooner along with the rum and sugar he imported for his mercantile.

His sister-in-law, Mercedes Louise Percival, known to island society as Mrs. Isadore Dyer, was quite the green thumb and had soon propagated and shared hundreds of these shrubs with her friends and neighbors.

These first cultivars became popular throughout the island and soon made their way into the gardens of other Texas communities.

Over the years, Galveston and a number of Texas gardeners cultivated many more varieties, including a pink, vanilla-scented one named ‘Mrs. Isadore Dyer’ in her honor.

They had a second heyday decades later, after the hurricane of 1900 devastated the local landscape. With their adaptability and fast growth habit, not to mention those gorgeous flowers, they were the natural choice for reforestation.

After the hurricane rebuilding, Galveston became known as “The Oleander City,” and its tribute society (the IOS) was formed and incorporated in 1967.

Want to join the happy legions who grow this showy shrub? Keep reading and soon you’ll learn how to grow and care for oleander.

Propagation

Oleander shrubs may be propagated by rooting stem cuttings, or starting them from seed.

From Cuttings

Another easy-care aspect of these flowering shrubs is how simple it is to start them from a cutting taken in the early spring, before they start blooming and after they’ve generated new growth.

It will take about a year for the cutting to reach a size where you can plant it in the ground or a container.

To start, any time you’ll be touching any part of this toxic plant, be sure to don protective gloves (I prefer disposable) and wear long sleeves. The saponins can be irritating to the skin.

Next, cut a stem that’s six to eight inches long from the parent plant. Make sure you’re cutting new growth, and make the cut just below a leaf node.

Strip the leaves until you’re left with three or four on the tip of the stem, and carefully dispose of the discards in a sealed bag with the household garbage.

Place the partly stripped cutting in a cup with three inches of tap water. Place the cup in a window with indirect light.

Within a week or two, your cutting should sprout roots. The water will get icky every two or three days, so you’ll need to change it at least that often.

Once the roots have reached an inch to two inches long, pot the plant in a six-inch container filled with well-draining soil. It will need at least four hours of direct or indirect sunlight per day as it continues to grow.

Every few months, plan to move it to a container that’s a size bigger. Within a year, you’ll need a gallon-size container and it will be about a foot tall, ready to be planted in its forever home.

From Seed

Seeds are also an option for propagation, and they tend to be available in more varieties than the potted plants you find at the garden center, so this could be worth a try.

To start seeds indoors, fill a shallow tray or one- or two-inch peat pot with about an inch of pre-moistened soilless mixture.

Press a couple of seeds into the top of each pot, or several into the tray, spaced about two inches apart.

Oleander seeds need light to germinate, so only cover them with a light sprinkle of the potting mixture or a bit of vermiculite.

Cover the pots or tray with plastic wrap and place on a windowsill, or on top of a heat mat that will create the ideal temperature for germination, which is 68°F.

Until you spy sprouts, which usually takes two to three weeks, keep the potting mix moist (but not waterlogged) with a spray bottle of water.

They may take up to 30 days to sprout, and I’ve heard a few sad tales of seeds that took 90 days to germinate, but that’s a rare occurrence.

Once they do germinate, immediately get rid of the plastic and place them where they’ll receive four hours of direct light or more per day. If you can only provide indirect light, they’ll need more like 10 hours of exposure each day.

You may want to consider investing in a grow light for this project.

When the seedlings form two sets of true leaves, they’re ready to be transplanted into individual pots.

Proceed as described above for propagating cuttings, moving to increasingly larger pots and continuing to care for them indoors, with the goal of having them ready to plant in early fall or early spring when the seedling is one year old.

How to Grow

I dislike being a downer about this shrub when it’s so beautiful and gardening is so much fun. But at the risk of sounding like a nag, I have to remind you: oleander is potentially dangerous.

If you want to grow this beautiful, carefree, flowering shrub, you must first make sure you’re able to cultivate it somewhere that pets, livestock, kids, or even adults won’t accidentally ingest any part of this plant, which is poisonous – from leaves to stems, and roots to flowers.

Once you’ve cleared that hurdle, the rest of the growing process is pretty simple.

These hot-weather beauties grow best in full sun, but you can inflict part shade on them, too. Do expect plants grown in part shade to be a bit leggier and to have fewer blooms than their full-sun counterparts.

As mentioned earlier, they don’t need good soil or any particular pH level, but the dirt has to be well-draining.

Consider adding a bit of sand to the planting hole or amending the soil with organic matter, but don’t fret too much if your drainage is so-so; as long as the plants don’t end up in standing water, they should be alright.

They typically go dormant in winter (though they may bloom year-round in a few sultry locales), and do the bulk of their growing and blooming in spring and summer.

This means the best times to plant oleander are very early spring, ahead of that growth spurt, or in late summer to early autumn, right after they’ve paused the bloomfest.

Plant each shrub in a hole that’s precisely as deep as the root ball, and two to three times as wide. Reserve the soil from digging to backfill after you plant.

Place the transplant in the hole, making certain to position the base of the main stem right at soil level (not beneath the ground).

Gently fill the hole halfway with soil, but don’t pack or press it down. Water lightly, being careful to aim for the roots and keep the leaves dry.

Give it a few minutes for the roots to get a drink, then gently fill the rest of the hole with dirt, give it another drink, and you’re good to go.

You may not need to tend these transplants again for months! But as the season unfolds, you may want to water occasionally during dry spells. These vigorous plants will tolerate drought, but hey, they’d prefer not to.

If you have the means and happen to think about it, consider watering them during the hottest or driest months in your region. An inch or two of extra water per week should help them to flower more profusely.

Make sure to aim spray from a hose or watering can at the roots and below the leaves, and don’t overdo it. If these shrubs end up in standing water, particularly during the cooler months, they can succumb to root rot.

Along with the below-leaf watering strategy, be sure to provide the well-draining soil they need so Mother Nature won’t overwater them, either.

To grow oleander in containers, choose a planter that’s twice as wide as the rootball.

It helps if the soil is amended with compost, both so it will absorb water and so it will drain properly.

Container-grown shrubs don’t need fertilizer, either, but they will need full sun and they might require extra water as soil in containers tends to dry out faster than soil in the garden.

Most importantly, if you’re planning to bring the container indoors when it starts freezing at night, make sure you’ve got a safe spot where pets and kids won’t be tempted to touch or gnaw on the plants.

You can learn more about how to grow oleander in containers in our guide. (coming soon!)

Growing Tips

- To protect yourself from the toxic, milky sap, always wear gloves and long sleeves when working with oleander.

- Provide an inch of water per week in very dry weather.

- If the leaves start to yellow, pluck them off and cease providing supplemental water.

Pruning and Maintenance

We promised no maintenance, and you can honestly go that route once your oleander shrub is established.

Fertilizer, for example: Mature plants don’t need it.

You can deadhead spent blooms with pruning shears to encourage more in the following years, but this chore only yields maybe 20 percent more flowers.

You can do without pruning, too. But your plant will also flower a bit more if you snip the suckers bursting out of the base stem or up from the roots if you find more than one or two.

And since oleander blooms on new wood, it can help to snip a few inches off the ends of the stems once the flowers have died back in late summer or very early fall. This provides more potential “blooming ends” the next year.

If you decide to give the shrubs an autumn trim, just make sure to schedule it early enough so the newly-rejuvenated branches are able to “harden off” before the first hard frost.

You can also prune again in early spring, right before the growth-fest gets going a few weeks after your average last frost. This can help your shrub to put on fuller growth, or stay at the height you’d prefer.

If you’re going that route, make sure to time it so pruning doesn’t interfere with prime growing season. And make your cuts right above leaf nodes.

But again, any form of pruning is just “nice to have” with these plants, and not at all necessary.

This may call me out as your sort of lazy friend, but I say, if you decided to grow this shrub because it’s low maintenance, you should stick to the plan! Skip the extra effort.

To learn more about how to prune oleander, check out our guide. (coming soon!)

Cultivars to Select

Your main choice when selecting cultivars is whether you want one that can grow tall, or prefer a dwarf variety that will top out at three to six feet.

There are different bloom colors, too – mostly whites, reds, and pinks, with the occasional purple or salmon shade.

And there are lots of cultivars available, with fun names like ‘Austin Pretty Limits.’

‘Austin Pretty Limits’

‘Austin Pretty Limits’ is a dwarf cultivar with dark pink flowers that grows just four to six feet tall.

You can find single live plants available from Burpee.

There is also a tall pink type that can grow to 15 feet and spread 10 feet.

Oleander

You can find shrubs in #1 containers available from Nature Hills Nursery.

You may be fortunate enough to be able to take a cutting from a friend or colleague’s established plant. But if you’ve got a yen for one of the more unusual cultivars, you may be more likely to find them available as seeds than bare root or potted seedlings.

To find more selections, check out our guide to oleander varieties (coming soon!).

Managing Pests and Disease

Because it’s so toxic, you don’t have to worry about deer or rabbits eating these shrubs.

There is the oleander caterpillar, Syntomeida epilais, to contend with, though, and this bug didn’t get its name accidentally: It’s the main pest that plagues this shrub.

The larvae can devastate the young shoots, and if you spot only skeletal remains of foliage, there’s a good chance your plant is infested with these pests.

The mature caterpillars are a sight to behold – otherworldly, fuzzy, rust-red crawlers sprouting black tufts.

But here’s what’s almost charming. If your plant is already growing strong, an infestation of these caterpillars will merely defoliate it. It will be down (and look awful), but not out.

It will probably just grow back and proceed along. That doesn’t mean you want to encourage the namesake caterpillars, though.

Their munch-fest can weaken the plant and make it more susceptible to the less likely pests, which include aphids, mealybugs, and scale insects.

Usually, though, you can spot where the larvae have scraped the leaves in time to cut the foliage they’re feeding on, and get rid of them in the process.

Or, if you spot the mature ones, pick them off by hand – they don’t sting! Ironically, the bigger danger to you is getting the irritating milky sap from the plants on your hands or arms, so make sure to wear long sleeves and disposable gloves for the duration.

Also look for the cocoons of mature oleander caterpillars, which are noticeable on walls or eaves of nearby structures, like a house or shed. If you pluck and freeze them for 24 hours before tossing them out in a bag, you can stop the damage before it starts.

These plants are hardy and thrive on neglect. But you’ll still want to make sure they’re not suffering from Botryosphaeria dieback, where species of fungi in the Botryosphaeria genus cause the shoots to die back and turn a depressing dark shade.

It’s pretty easy to take care of the damage, though, pruning out all the discolored portions and making sure to treat any cuts with a solution of one part household bleach to nine parts water.

They may also have a bit of difficulty with oleander gall, which comes about when a bacteria called Pseudomonas syringae multiplies inside the plant. It enters via the shrub’s natural openings in the leaves and stems, or through wounds sustained from frost or pruning injuries.

Galls start out as small bumps and develop into warty, knotty growths almost an inch wide.

To prevent these bacteria from taking hold, avoid pruning during the rainy season. Also, don’t water the plants from above. Either process runs the risk of the bacteria that causes gall splashing from a diseased plant to an unaffected one via water droplets.

Once you’ve noticed gall, you can remove the lesions by pruning a couple of inches below each growth. Treat each cut you make with a solution of 10 percent household bleach to 90 percent water.

Be diligent about discarding the remains when you prune any diseased portions of this toxic plant.

You don’t want to burn them, since smoke from oleander can cause respiratory distress and may be fatal to humans and pets that breathe it.

Nor should any cut branches with gall lesions go into the compost, or they may spread the bacteria and cause more damage.

Instead, bag the cuttings and throw them away with the household trash, and then destroy any lingering bacteria on your pruners by washing them one more time with that 10 percent bleach solution.

Best Uses

If you’ve got a spot with full sun and well-draining soil in Zones 8-10, oleander will thrive!

Remember you do have to plant it where no pet or person will ingest any part of this poisonous plant. But there are still several satisfying options for growing this hardy ornamental shrub in your landscape.

The tall varieties excel as a quick-growing, flowering privacy screen, for example, with the added advantage of evergreen leaves.

Or you can pull together your landscape design by planting midsize or dwarf types to form a lower, mounding hedge.

In more formal settings, consider planting just one, and training it to grow like a single-trunk tree.

If you’re lucky enough to garden where spray from the ocean or bay is an issue, salt-tolerant oleander should top your list of ornamental shrubs. It’s extra nice as part of seaside gardens because it can act as a windbreak, either singly, or as part of a hedge.

Since they’re so low-maintenance, thriving without supplemental water or fertilizer, these shrubs are also a great option for planting somewhere that needs brightening but is far from a water hose or otherwise inaccessible.

You can also plant oleander in spots where you crave color but it would be tough to amend the soil or where there is part shade. These shrubs will adjust and go on blooming!

Behind the garage, on that hard-scrabble patch in the far corner of the back yard, in that gully or ridge where no one can walk – much less carry a watering can – these are all great places for oleander.

And if you’ve had trouble with deer eating every blooming thing, consider planting a few of these shrubs in an isolated part of the landscape. Deer won’t touch them, and you’ll have uninterrupted enjoyment of the profusion of blooms.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Evergreen flowering ornamental shrub | Flower/Foliage Color: | Pink, purple, red, white/green |

| Native To: | North Africa and eastern Meditteranean | Maintenance: | Low |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 8-10 | Tolerance: | Drought, heat, poor soil, salt air |

| Season: | Summer-fall | Soil Type: | Average |

| Exposure: | Full sun | Soil pH: | 5.5-6.5 |

| Spacing: | 4 feet (hedges), 8 feet (specimens) | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Planting Depth: | Slightly above soil grade (transplants), soil surface (seeds) | Avoid Planting With: | Vegetables or near areas where pets and children could ingest |

| Growth Rate: | Medium to fast | Uses: | Hedge, privacy screen, ornamental specimen |

| Height: | 8-12 feet (standard), 3-5 feet (dwarf) | Family: | Apocynaceae |

| Spread: | 2-10 feet, depending on variety | Genus: | Nerium |

| Water Needs: | Low | Species: | oleander |

| Pests & Diseases: | Oleander caterpillar, aphids, mealybugs, scale; Botryosphaeria dieback, gall |

Oleo You Need to Know About This Heat-Tolerant Shrub

At the end of the blooming season, I would challenge you to find a flowering shrub that is more productive than oleander, especially considering the minimal care it requires.

If you’re facing drought, high humidity, high temperatures, and maybe a bit of salt air, this vigorous shrub is a friend indeed.

How about you? Do you have an oleander anecdote you’d like to share, or maybe a favorite variety or growing tip? Let us know in the comments section below!

And for more information about growing ornamental shrubs in your garden, check out these guides next:

© Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Product photos via Burpee and Nature Hills Nursery. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock.

About Rose Kennedy

An avid raised bed vegetable gardener and former “Dirt to Fork” columnist for an alt-weekly newspaper in Knoxville, Tennessee, Rose Kennedy is dedicated to sharing tips that increase yields and minimize work. But she’s also open to garden magic, like the red-veined sorrel that took up residence in several square yards of what used to be her back lawn. She champions all pollinators, even carpenter bees. Her other enthusiasms include newbie gardeners, open-pollinated sunflowers, 15-foot-tall Italian climbing tomatoes, and the arbor her husband repurposed from a bread vendor’s display arch. More importantly, Rose loves a garden’s ability to make a well-kept manicure virtually impossible and revive the spirits, especially in tough times.

[ad_2]

Source link

+ Planting String of Watermelon Succulents

+ Planting String of Watermelon Succulents  with Garden Answer

with Garden Answer