In 2014, Barcelona-based architect and urban designer Carmen Fiol-Costa became the first Droga Architect in Residence, spending three months in Australia forming connections with architects, academics and students.

The founder of Arriola and Fiol Arquitectes is an advocate for urban regeneration and the importance of the public realm in all architectural projects. During her residency she focused on the Australian landscape and its connection to urban design, and developed a case study based on Liverpool, Sydney, aimed at enhancing urban spaces through architecture. ArchitectureAU assistant editor Josh Harris spoke to her about her experience, her impression of Australian urbanism and an unfortunate accident that led to a trip to the hospital.

Josh Harris: You were the first Droga architect in residence. What were your expectations of the program, and what did you hope to achieve?

Carmen Fiol-Costa: I knew already a little bit about Sydney and Australia; I had been invited by Rob Adams [City of Melbourne’s director of city design] several times, and then I had some architect friends in Sydney, like Helen Lochead, who I met at Columbia University. I wanted to have a new experience as a scholar, but also to have the opportunity to see a new market for my practice, to get to know the architectural panorama, and the architects, to see the work.

The objective of my stay there was to interchange with the government architect, who was Peter Poulet at the time and his office, and also with the University of Sydney, the urban design program with Roderick Simpson. And then to get to know the academics and explain my work as a practitioner. Brit Anderson and the team who chose me asked me to produce a report, Urban Civic Projects, and it built on the concept behind my work with Arriola and Fiol, which is about making projects that can be interesting and make better the city where we live.

As an architect, I deal with architectural projects as buildings, also as public spaces and also as a landscape and urban design. With “urban civic projects” you have three lines: one is the building, the other is the square, the other is the network of streets. And when you deal with one of these three elements, you have to look at the other two in order to make a project for people, to improve the quality of the space of the city.

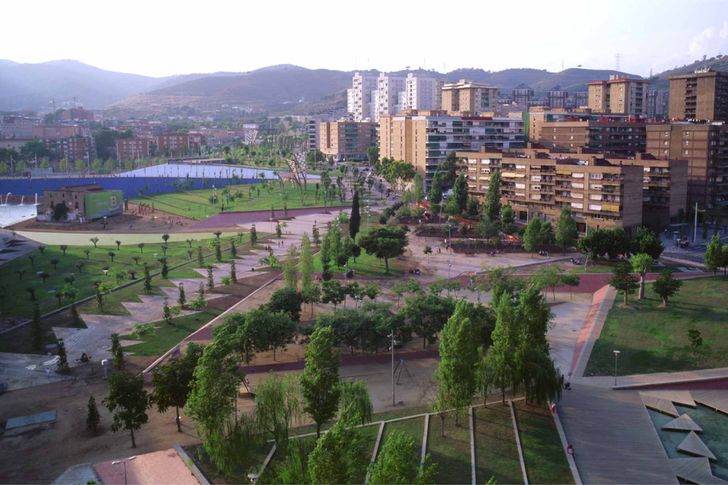

Parc Central de Nou Barris, by Arriola & Fiol Arquitectes, a park between 1960s housing blocks.

JH: I know that the public realm is very much at the centre of your work. Many of your projects are about reconstructing fragmented public spaces and transforming them into more successful urban landscapes. What are the qualities that make a successful public space?

CFC: I’ve been doing a square lately, Crown Square in Manchester [shortlisted in the 2019 AJ Architecture Awards], and what makes it successful is that people use it. If a place has no character, it [needs to be] transformed into a singular place that is recognized, where people want to go. In terms of design and space, it [should] connect the activities of the buildings with the activities of the square and the amenities.

Barcelona, 30 years ago or more, for instance, was a secondary city in Europe. Now it’s one of the first cities in Europe. This was because before there was not democracy. I worked in the [Urban Design Department of the City of Barcelona] as a young architect, and we worked to revitalize the city, because for 40 years before that, nobody did anything. It was a question of revitalizing economically the city and making it better because we were not proud of the city. You have to be proud of where you live.

JH: When you were in Australia as part of the Droga program you said you wanted to create better exchange between countries, so that architects know what works in different cities and what doesn’t. What lessons can other cities learn from Barcelona’s revitalization? Could you draw comparisons to Sydney, for instance?

CFC: Well, Sydney is a very beautiful city. Barcelona is denser and you can walk the whole city. Not in Sydney. You have these highways, sometimes too many highways.

Barceona is not based on skyscrapers. The idea of being a city of power, of money, of corporations, that’s still in the mentality in Sydney, I suppose it’s the same in Melbourne. Here we try to keep the buildings low, as in Paris, because we think the urban tissue in the city disintegrates when you are dealing with skyscrapers. And I have seen that a lot of architects in Sydney – not all of them, but enough of them – they do whatever to build. And I think it’s not necessary to build, if you don’t do anything that’s interesting. It’s just for money.

[During the Droga residency] I had been in contact with the City of Liverpool. In my report on urban civic projects, I tried to make an example of Liverpool because I had evening workshops with different offices and architects, and I tried to make the workshop about this city. I envisioned a three-dimensional proposal for the core of Liverpool [which explored how] to see it as a city, how to deal with the main plaza, how to take a “civic approach” in the city.

JH: How did you present this work? What sort of response did you did you get from your intervention?

CFC: At the end of my stay, I did a presentation in the wonderful Droga apartment in Surry Hills and everybody came. Oh, it was a party, so I don’t think anybody paid a lot of attention! But then I gave to everyone I had a relationship with copies of my report – so everyone knows about it.

The office of the Government Architect had commissioned some projects [for Liverpool] and I thought that these projects had to have an overall scheme. And this is what I tried to make happen, to create a framework to understand the position of Liverpool within the metropolitan area of Sydney, to understand the connection to the river, to understand what makes the city an important place.

I created a model and an exhibition with a photo map, and then also I did a painting because I thought that what’s very important was the connection between art, geography and landscape and city.

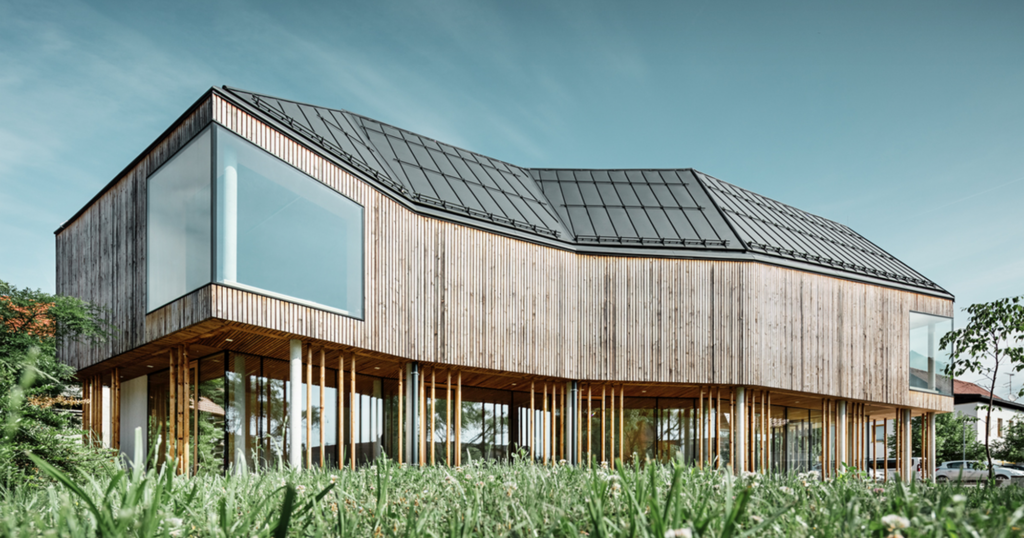

Functional sculpture in Parc Central de Nou Barris.

Image:

Beat Marugg

JH: How does this relationship between landscape and art and architecture inform your work?

CFC: This is very important, all over [the world]. Take Stonehenge, for example, which I visited several years ago. There’s this big stone monument, a Celtic monument, in a place where people once lived. This was the place where they were perhaps gathering to connect with the earth and the gods, or whatever. But this place is in a specific geographical position, and it relates to the whole village, the whole city, the whole structure of agriculture. And this is the same thing that the Aboriginal people in Australia do.

This is important to recover [where you have] this geography of big sheds or big suburban houses, to retrace the different layers of geography, and not build in places where you should not build. You can build everywhere with a bigger skyscraper, but you shouldn’t.

JH: I guess since colonization, Western architecture in Australia has often been fighting against the landscape, rather than working with it.

CFC: Yes. But it’s not just Australian [architecture]. It’s all Western architecture after industrialization, and big capitalism. [The focus of architecture became] just to take profit, not to use it or to live just to extract. This complexity is interesting, and this is what I was trying to show in my lectures in Australia.

JH: Could you talk a little bit about the value of the Droga program? What sort of impact did it have on your work?

CFC: It has had an impact in my life, I think, because I broke my foot! On the fourth day I broke my foot, I went to hospital and had an operation. I couldn’t see a lot of things [while recovering] but you see things from a different point of view. I made a lot of friendships; just in three months, and in the first week I made very good friendships, apart from the ones I had already.

JH: Have you kept up collaborative relationships?

CFC: Yes, I have. Richard Frances-Jones, who I met in Barcelona when he was a colleague at Columbia University, we collaborated on a project with a big team, also with a class at Barangaroo. It was a very strange project, but it was very nice, this collaboration. Also, I did some competitions with other people. We are working in Paris, in England and also in Italy and so I thought that by building these relationship, I could come to the country more often. I like Australia. I will come again soon, if we can ever travel again.

JH: The last question I’ve been asking everyone is, how did you like living in the Durbach Block Jaggers apartment?

CFC: Yes, I enjoyed staying there. I liked it very much because it was industrial. It was in a place that was quite lively, and I could see the train, the infrastructure and the sky.