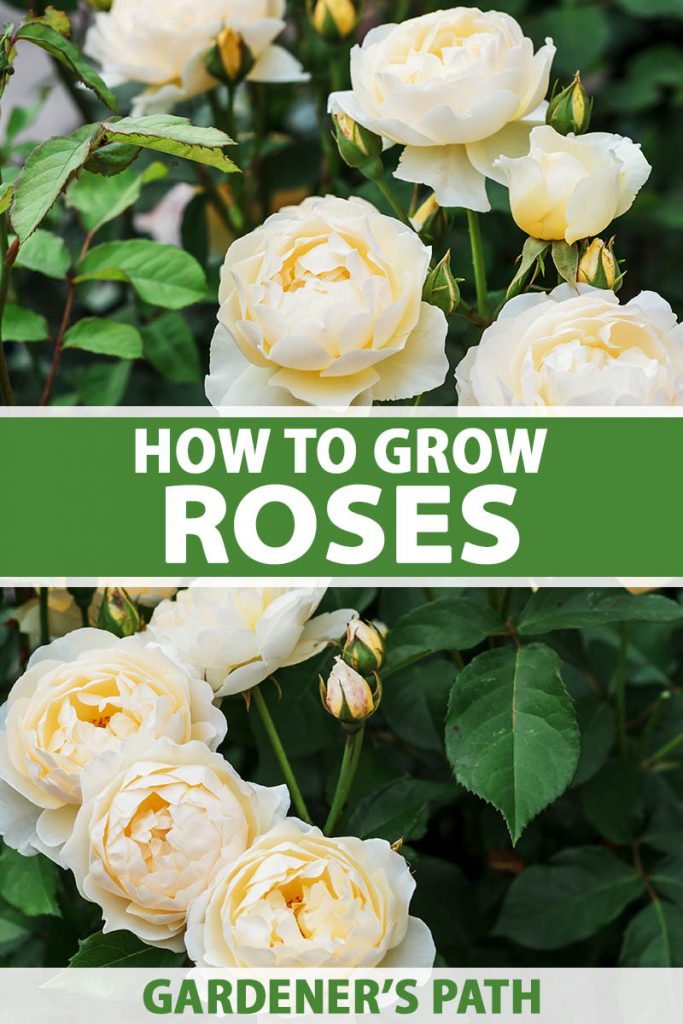

Rosa spp.

There’s one thing that I constantly run into when talking to gardeners who are interested in growing roses:

A sense of being overwhelmed. There seems to be so much involved, right?

It’s true, there are a ton of different varieties and cultivars, from wild to floribunda to tea roses. It’s also true that growing them can sometimes be challenging. But it doesn’t have to be complicated or stressful.

Start small with one plant, and see how you feel about living with these garden glories. If you’re anything like me, you’ll end up falling in love.

I used to hate the idea of growing roses, partially because I didn’t like growing anything that I couldn’t cook with, or anything that was overly fussy.

But I purchased a home from a woman who had won awards for her roses, and I couldn’t bring myself to pull them up.

That’s when I discovered that these floral classics aren’t the pampered relics that I thought they were. Many are quite hardy, and the payoff is undeniable. There’s a reason these flowers have become a staple in gardens across the globe.

Plus, I found they took much less work to care for than I expected. In fact, it seemed as though the more I felt like I had neglected the stunners, the more they gave back.

Working next to a mason jar filled with heady blooms cut and brought inside from the garden, by the time I made my first batch of rose hip jam, I was a complete convert.

And I’ve come to realize that roses don’t take any more time or effort to care for than the peonies or hydrangeas that I adore. You only need a touch more knowledge up front.

That said, if you are bitten by the rose bug, you can definitely fall down the rabbit hole as a result.

There is a seemingly infinite variety of colors, sizes, and shapes to choose from.

Roses are available that can grow in practically any location, spanning USDA Hardiness Zones 3 through 11, with drought tolerant types as well as cold hardy varieties suited to various climates.

And you can shape them, let them climb, keep them pruned to a petite stature, or grow them just for food, enjoying the ornamental qualities of the flowers as an added bonus.

Let me assure you – it may seem as if you need a 200-page user guide just to keep these plants alive, and there are many useful published resources out there in book form that are very helpful.

But let’s save the books for later. This guide will get you on your feet and ready to tackle this iconic bloomer, with everything you need to get started.

Here’s what we’ll cover:

We won’t go over the advanced stuff here. Instead, you can expect to learn the basics so you can get going without feeling overwhelmed.

Ready? I know I am!

A Short Rose Primer

Before we jump in, I think it helps to understand the names of the parts of a rose plant first. Let’s take a look at what we’re working with.

At the base, of course, you have your roots. On top of those but below the canes, you’ll often find a little bump or knot-like spot. This is the graft union, the location where the rootstock and the scion were joined.

The scion is the part that has the qualities that you’re looking for (i.e. the specific species or cultivar that you purchased) whereas the rootstock is selected for hardiness, adaptability, and the ease with which it is known to become established, among other qualities.

Many rose plants are grafted, which means a grower used one variety or species for the roots, and another for the tops.

The cane is the stem that supports the leaves and it will often have thorns, which are technically called “prickles” on a rose.

Roses have leaves that appear in groups of three, five, or seven leaflets.

The peduncle is the branch that supports the flower.

The hip is the base of the blossom. It starts out green and changes color after the blossom fades. This is the fruit of the plant.

Above that is the sepal, which is the green outer covering that surrounds the flower bud, and it is visible before the blossom opens.

Roses have blossoms that can range from five to 40 or more petals each, depending on the type.

Some plants even have over 100 petals per flower, like the yellow shrub type ‘Molineaux,’ which has 120.

What’s technically known as a basal break is what we typically think of as a shoot, which is the new growth of the plant that emerges from the buds at the base.

Plants can be everblooming, which means they bloom all season long. Or they can be once-blooming, which means they’ll produce one set of blossoms per season and that’s it.

A third type is repeat blooming, which means you will see one set of flowers early in the season, and then one or two more flushes of blooms will follow as the season progresses.

On top of that, roses can be single flowered, semi-double flowered, or double flowered. Double flowered roses have multiple rows of petals that make up each blossom.

These are the fuller, more typical roses that most people might picture as the standard.

Single and semi-single roses have more gauzy, simpler blossoms.

Single types have a single row of petals, usually around five to eight petals each, surrounding the center.

Semi-double plants have more petals, but not as many as a double variety.

Roses can have different growth habits as well.

A standard or tree rose is a type that is trained to have a single trunk topped with a bushy head that resembles a small tree.

This is in contrast to shrub roses, which have a broad, dense growth habit.

You’ll also see ground covers, ramblers, and climbers.

If you’re a lazy rose grower (guilty!) or just beginning your journey, keep an eye out for self-cleaning roses, which don’t require any deadheading to get continuous blossoms.

Roses are hardwood plants, but when the canes are young, they’re soft and green. This distinction is important when it comes to propagation and pruning.

Cultivation and History

Scientists have found fossils of rose plants dating back 35 million years.

The Rosa genus is native to Asia, North America, and Europe, though the version we know today probably came from China, where it was likely first cultivated.

No one is certain, because this plant has been a part of human culture for that long!

It only grows wild in the Northern Hemisphere, and has been an important cultural symbol everywhere from ancient Rome through numerous Chinese Dynasties and to Medieval Britain.

The rose has been a symbol of love in India for thousands of years. In Japan, the language of flowers, known as hanakotoba, defines red roses as the flower of romance.

In the US, it’s difficult to imagine Valentine’s Day without supermarkets and florists’ shops filled with bouquets of long-stemmed beauties.

Clearly, this is a plant that has become an important part of human culture wherever it grows.

Propagation

There are about as many ways to propagate roses as there are varieties of plants in the Rosa genus.

Okay, that’s a slight exaggeration. But this is most definitely a plant that people have spent a good deal of time figuring out how to reproduce.

From Seed

It’s possible to grow them from seed, but that doesn’t mean it’s an easy or fast process. It’s definitely rewarding, though!

Our guide to starting roses from seed is covered in our guide (coming soon!). For now, here are the basics:

To get started, purchase seeds or harvest your own.

If you’re planning to save your own seeds, note that some hybrid varieties are sterile, or they may not grow true to type.

Plus, you never know exactly which type of rose pollinated a given flower if this happens naturally, since bees and butterflies usually handle that job. But it can be a fun surprise to see what you get.

This is different from what happens in a professional breeding situation, where a breeder manually pollinates the rose to ensure that it doesn’t hybridize in an unwanted way.

Snip rose hips off the plant after they have been allowed to mature for about four months.

Store the hips in the fridge for a few weeks if you can’t get to work right away. Otherwise, you should remove the seeds from the hips immediately after harvesting.

To do so, cut each hip in half and scoop out the seeds with a teaspoon. Soak the seeds in a solution of one part bleach to 20 parts water for a minute or so, and then rinse in a fine mesh sieve under running water for about a minute.

Place the seeds in a bowl of clean water and set them aside to soak. After about five minutes, toss out any seeds that float – these may not be viable. Continue to soak the seeds for 24 hours, then drain and rub them on a cotton cloth to remove any remaining pulp.

Set them out on a towel in a cool, dry place to dry completely, and then place them in a jar or envelope for storage. Keep them in a cool, dark place until you’re ready to plant them.

To start the germination process, you need to cold stratify the seeds. To do so, moisten a paper towel and place the seeds inside, folding the towel over them.

Place in a ziptop plastic bag in the fridge at 38°F. Check periodically to make sure the paper towel remains moist, and let them sit for four to six weeks.

At this point, the seeds should begin to sprout. Transplant them directly into the garden 1/4 inch deep, and keep moist until the seedlings are about three inches tall.

Be patient, as this can take anywhere from one to four months.

If you decide to get into advanced rose seeding, you can cross-pollinate different types to combine the traits of two plants.

We won’t go into that here, but be aware that it’s an option as you get more advanced with propagating these incredible plants.

From Cuttings

Roses readily reproduce from cuttings. The best time of year to take them is in the fall, but you can do it any time you want really.

We cover the advantages of taking cuttings in autumn and go into further detail in our full guide. (coming soon!)

First, find a stem that has recently bloomed and snip an eight-inch piece off at a 45-degree angle. Immediately put the cutting in a glass of water, where it can stay for a few hours if you aren’t able to plant it right away.

You can plant cuttings directly in the soil, or in a container. Use fresh potting soil and a four-inch or larger container.

CowPots Biodegradable Plant Pots

You can use standard plastic containers, but I prefer biodegradable pots ones like these CowPots, available from Amazon.

Once you are ready to plant, strip the bottom half of any leaves – watch out for any thorns! Dip the cutting in rooting hormone powder or gel.

Create a hole in the soil using a pencil and stick the cutting inside so that half of the cutting is submerged.

Plants need about eight inches between them as they mature if you put them directly in the ground. Plant no more than one cutting per four-inch container.

Keep the soil moist as you wait for the cuttings to grow. It’s vital that they not dry out.

You can place a cloche over the cuttings to assist with this, but watch so that they don’t overheat in the sun.

If you keep the cuttings indoors, put them in direct sunlight for at least six hours a day.

You will know it’s time to transplant when the cuttings have developed a good root structure. Give them a gentle tug and see if the cutting resists, and if it does, the roots have developed enough.

You can plant in the spring as soon as the soil can be worked or in the fall about six weeks before the first average frost date. When the plants are ready to stick in the ground, harden them off for a week first.

Place the cuttings in indirect sunlight for an hour, and increase the time spent outside by an hour each day until the plants can handle a full eight hours outdoors.

Layering

Roses can be propagated by layering hardwood cuttings. In the spring, summer, or fall, look for a young cane on the outside of the plant that can be bent easily.

Gently bend the cane to the ground, then create a slice about three inches long and halfway through the cane where it touches the soil.

Dig a long trench about four inches deep. Place a rock on the free tip of the stem to hold it in place, and another closer to where it is attached to the plant to hold it down.

Bury the rest of the stem in the soil.

Water thoroughly, and cover the area with an inch or two of well-rotted manure.

After about eight weeks, remove the rocks and give the cane a little tug to make sure it has developed roots.

If it resists, snip the cane away from the main plant. Dig six inches down and 12 inches around the rooted area.

Plant as you would a transplant, keeping the plant as deep as it was growing in the ground originally.

Transplanting

One of the easiest ways to add roses to your garden is to buy a plant that’s ready for transplanting.

These are usually available in one or five-gallon pots as live plants, or as dormant plants in soil with small, leafless canes.

You can also find bare roots that are ready for planting, which we’ll cover briefly below, and in a separate guide.

Dormant plants should go in the ground within a month of purchase, but plants that have leafed out can stay in their container for up to a year with regular watering.

While you can buy roses year-round from many plant nurseries, the best time to get them in the ground is fall or spring in most growing zones.

Look for plants with at least three healthy-looking canes that are plump and green, or buy online from reputable sellers that guarantee their plants.

Dig a hole four inches wider than the pot that it came in. Amend the soil that you dug out with one part well-rotted compost to three parts soil.

Put the plant in the hole and backfill halfway with your prepared soil, then soak the roots with water. Fill the soil in the rest of the way and soak again.

Wild roses can be planted in a hole about the same size as the container they came in.

A good rule of thumb is to match the volume of water with the size of the container, so aim for three gallons of water for a plant that came in a three-gallon pot, for example.

Be absolutely sure to bury the knot (aka the graft union). That’s the little bump at the base of the stem.

It doesn’t matter how deep the plant was in its nursery container, the knot should just barely be covered by the soil when you transplant it.

From Grafted Rootstock

Like I mentioned above, most roses that you can purchase in bigger nurseries or stores are grafted.

This means one variety is grafted onto the rootstock of another variety, typically because the top rose is less hardy than the one used for its roots, but it has desirable qualities like particularly beautiful blossoms.

The rootstock provides strength and the scion provides pretty flowers.

Typically, this gives you a larger, more robust plant than you would get if you were growing one with its own roots (known, fittingly, as own-root roses).

Of course, every once in a while a grower (particularly home growers) might graft a plant that doesn’t end up being improved by the grafting.

The rootstock might not be as tough as they’d hoped, or the flowers might be unimpressive. But most commercially available plants have been thoroughly tested, so you probably won’t encounter this issue.

While grafting used to be the norm, these days you’ll see just as many own-root plants.

If you have the choice, I’d recommend that you pick plants that have not been grafted because they have a broader base in place to get the plant going, meaning they can more readily become established.

That said, many roses grown solely for exhibiting or cutting are only sold as grafted plants.

That’s because grafting allows a breeder to have more control over particular characteristics like blossom size, petal numbers, and disease-resistance.

Bare Roots

Bare root plants need to go in the ground immediately after purchasing them. Before planting, trim away any dry roots.

Then, plant as you would a transplant, filling in around the roots carefully with your prepared soil.

After you have buried it, mound well-rotted compost around the base to six inches. This keeps the plant protected as it develops feeder roots, which can take up to a month.

At that point, you can move the compost away from the plant and spread it out.

How to Grow

First things first, test your soil. This is essential to figuring out if you need to add any nutrients or alter the soil’s pH.

While you may have the ideal soil available for planting roses already, most gardens don’t.

Roses need loamy, well-draining soil with a pH of 6.0 to 6.5.

The roots of these plants are somewhat shallow and can be quite extensive, spreading as far as the plant is tall.

Dig a hole 18 inches deep and 24 inches wide to loosen the soil, and remove any rocks, weeds, or debris.

Amend as needed. Sand can be added if you have heavy clay soil, or you could amend with compost if your soil lacks organic matter.

Wild roses are an exception to these recommendations. Unless you have really sandy or heavy clay soil, you won’t need to worry about altering it much.

Avoid planting under the eaves of your home where snow or ice may slide off in the winter and damage them.

You should also put plants no less than 24 inches away from any solid walls or foundations at planting time, so they can benefit from good air circulation.

Roses also need protection from wind. When a plant is in full bloom, a strong gust of wind can easily break a cane.

Plant them near a fence or other tall plants, while still leaving at least 24 inches of space in between.

Don’t plant at the base of hills where frost pockets may form, and avoid planting in low-lying areas that may collect water.

Keep roses away from aggressive vines like ivy, honeysuckle, or morning glory.

Almost all types of roses need full sun, with at least six hours of direct sunlight per day.

However, there are types that grow well in part shade, so be sure to do the research to determine exactly what your chosen plant needs.

If you do give your roses some shade, make sure it is in the afternoon rather than the morning.

Watering takes a little extra care to avoid problems down the road. You always want to water at the base of plants, in the early morning so everything can dry out before nightfall.

That said, it’s fine to spray your plants as needed on a sunny day to address pest issues if you need to.

Give roses about two inches of water per week. If you don’t get that much rain, you’ll need to provide supplementary irrigation.

How can you tell? Buy or build a rain gauge, an invaluable tool in the garden for growing all kinds of plants.

Don’t feed newly planted roses. Give them some time to become established and to do their thing.

Once you start to see true leaves emerging on new growth, it’s time to break out the food.

Neptune’s Harvest Organic Seaweed Plant Food

Select a fertilizer targeted at root growth like Neptune’s Harvest Organic Seaweed Plant Food, available via Amazon, for supplementing plants during the first six months.

Then you can switch to a standard fertilizer.

Great Big Roses Natural Compost Extract

There are many different products made just for roses, like Great Big Roses Natural Compost Extract, an organic plant food that’s available on Amazon.

If you decide to go with something else, just be sure to avoid anything that is high in nitrogen. Otherwise, you might find that you have a ton of leaves and very few blossoms.

Growing Tips

More than some other types of plants, roses need a bit of extra prep and care if you want the prettiest blooms possible.

- Most roses prefer full sun, but some will tolerate a bit of shade, so check your selection’s specific requirements.

- Be careful about where you choose to plant, and amend the soil if necessary.

- Fertilizer isn’t optional if you want healthy flowers.

Pruning and Maintenance

Roses won’t continue to grow and spread forever. Eventually the older canes die off, and new canes emerge. Those old canes will need to be removed.

You also need to prune plants to ensure that they stay healthy and in shape, and to provide protection for the coming winter.

Beyond that, pruning can help to control pests and disease, and can encourage another round of blossoms.

You can prune in the spring, during the growing season, or in the fall, just before plants go dormant. Deadheading should be done when blossoms are finished, continuously throughout the season.

Keep them pruned to a few inches away from walls or other structures, to maintain adequate spacing.

When your plants are growing throughout the spring and summer, keep these three qualities in mind: brown, bent, or burnt. The first two are self-explanatory. Burnt plants may look orange or rusty in color, or they may be dry.

If you see any canes or buds that exhibit any of these qualities, trim them out, cutting down to the first node on the stalk that has five leaves attached. The node is the spot where the five-leaf leaflet joins the stem.

Also keep an eye out for blind shoots, which are branches that emerge but don’t form a bud. This is usually caused by an untimely freeze.

Just trim them away and the stem will likely send up another blossom later on.

We have an entire guide to helping you prune your roses the right way, whether you’re doing it for aesthetics or for health.

Note that you shouldn’t trim your roses at all in their first year in your garden.

Mulch around the base of your plants, but make sure it is not touching the canes. Well-aged sawdust or manure, grass clippings, or hay are all good options.

A three-inch layer of mulch will not only keep weeds away, but it can help to prevent water loss as well.

Types to Select

The advantage of buying roses, rather than propagating plants via seed or cuttings, is that there are literally hundreds of varieties available for purchase by home gardeners today.

And while you can’t buy them all currently, according to Paul Zimmerman, author of “Everyday Roses: How to Grow Knock Out and Other Easy-Care Garden Roses,” there are actually over 7,000 identified commercial varieties of roses.

Everyday Roses: How to Grow Knock Out and Other Easy-Care Garden Roses

If you’re interested in learning more, this book is available on Amazon.

Roses can be grouped into three growing styles: climbing, shrub, and ground cover.

While some types can require some advanced skill to grow successfully, many are well-suited to the beginner.

Climbing types produce long canes that can climb along supports. They don’t send out suckers or tendrils to grip onto things, so you need to tie them in place.

Shrub types have a bushy growth habit. Ground cover types spread horizontally and stay under a foot tall.

You can broadly classify all roses as either species (aka wild), old or antique, or modern.

Modern roses came about after 1867 when the first hybrid tea rose was introduced, while wild roses are the less cultivated types that are closer to the original ancestors of the garden staples we know today.

I think it’s fascinating to compare wild roses (which are still around today) to the massive, showy hybrids that have been developed by growers because you can really see the difference between the simple wild blossoms and the showy show-stopping blooms that have been created through careful breeding.

You can further divide them into styles, but there isn’t any official guideline for this, so these categories can vary among aficionados.

If you want to learn more about the different types of roses, we have a whole guide dedicated to these endlessly variable plants. (coming soon!)

Many different varieties and cultivars are available from our friends at Nature Hills Nursery.

Managing Pests and Disease

I won’t lie to you, many roses are undeniably prone to pests and diseases.

I struggle with powdery mildew and spider mites every single year on some of my plants, while others remain completely untroubled (another reason to love wild and polyantha roses).

The one thing I’ve noticed is that air circulation is absolutely key. If your plants are overcrowded or too dense, you will likely have problems.

So remember: make sure your plants are getting lots of good air circulation and they’ll be much better off.

Still, if you grow roses long enough, you WILL run into trouble. Here’s what to watch for and how to deal:

Herbivores

You know how marvelous roses smell? And how tasty those hips can be? Lots of mammals out there are sure to find your roses to be just as irresistible as you do.

Deer

Deer will eat tender young buds and growth, as well as the leaves. You’ll likely notice ragged tears in the stems and leaves, and you may see missing flowers or buds.

Check around for deer poop to confirm that these ungulates have paid your plants a visit.

While you can use repellents, you can also buy motion-activated sprinklers, ultrasonic repellers, and lights to keep them away. Just keep in mind that they can blast Fido as easily as they can a deer.

Fencing is another good solution.

Rabbits

Rabbits particularly love to nibble on roses in the winter, but they’ll take a bite any time they can get their ever-growing teeth into your plants.

If it looks like the leaves, stems, or blossoms have been neatly sliced with scissors, you might have rabbits in the garden.

Confirm by looking for their droppings and check to see if all the damage is happening no more than two feet from the ground.

The best way to deal is by preventing them from being able to reach your plants. Fencing that is at least 26 inches tall with gaps no more than two inches wide will work.

You can also surround your roses with lavender, yarrow, or dusty miller, or veggies in the allium family, since rabbits don’t like these plants.

They’ll also avoid certain scents, like dog feces, bone meal or blood meal, or predator urine.

Learn more about how to keep rabbits out of the garden in our guide.

Squirrels

Feeling safe because you don’t live in an area with deer or rabbits? Not so fast! Squirrels will eat roses, too.

If you see little divots in your planting beds or partially eaten flowers, these small rodents may be to blame. Squirrels like to dig to look for food or to bury food they’ve already found.

One of the best deterrents I’ve found is to provide them an alternative food source in the form of a feeder.

They will generally ignore roses if a more appealing and more easily accessible food source is available. You can also sprinkle plants with cayenne pepper or garlic spray as a deterrent.

Insects

Roses and insects go together like peanut butter and jelly, but not always with such delicious results.

Bees and butterflies are beneficial, but aphids, mites, sawflies, thrips, and cane borers… not so much.

Aphids

There are a variety of aphids that will attack roses, but rose aphids (Macrosiphum rosae) or potato aphids (M. euphorbiae) are the most common.

No matter what type you have, they suck – literally. These tiny bugs suck on plants, causing discoloration and distortion of leaves and flowers.

If you don’t have a ton, regularly spraying the plants with a blast of water from the hose each day for a week can often get things under control.

Failing that, sprinkle plants with flour, which will constipate the little bugs.

Still struggling? I’ve been there. It’s time to break out the insecticidal soap or neem oil. Follow the manufacturer’s directions and reapply once more after you stop seeing any signs of them to be safe.

Read more about ridding the garden of aphids here.

Cane Borers

Cane borers are insects that chew a hole down the center of rose canes, where they make a nest and reproduce. Some stop just a few inches down the cane, while others go all the way to the crown.

On the bright side, they eat aphids. So they aren’t all bad, I guess?

Watch for clusters of yellowing leaves, wilting tips, or the small tunnels that the borers leave behind. The extent of the damage often depends on the specific type of borer that you’re dealing with.

The rose stem girdler (Agrilus aurichalceus) is known for causing canes to break or die beyond where the bugs enter the plant.

Flathead borers (part of the Buprestidae family of beetles) can kill off an entire plant, while Hartigia trimaculata girdles stems, usually several inches down from the top. They eventually work their way down to the base.

But these patterns aren’t always consistent, and one type may cause damage that looks like another type.

Don’t worry about identifying the specific type that you’re dealing with, as you will rarely see the insects, just the damage they cause.

Regardless of the type, the solution is to prune away damaged canes an inch below where the bug entered. Destroy the pruned canes.

Japanese Beetles

Popillia japonica are voracious eaters that will decimate roses (and raspberries, too).

I admit that they’re kind of pretty with their incandescent carapaces, but once I see the damage they’ve done, I forget all about their fetching appearance.

They’re about a half inch in length, and where there’s one, you’re bound to have a whole swarm waiting in the wings.

We have an excellent guide for dealing with Japanese beetles if you’d like to give it a read.

For now, just know that they can completely skeletonize a rose plant, so you want to act fast.

Sawflies

Sawfly damage often gets confused with that caused by Japanese beetles if all you can see are the marks they leave behind.

They both like to nibble on the interior of leaves, eventually skeletonizing them.

Sometimes this type of damage is actually caused by sawfly larvae. European rose slug sawflies (Endelomyia aethiops), bristly rose slug sawflies (Cladius difformis), and curled rose slug sawflies (Allantus cinctus) all look the same from a distance, and all of these will attack roses.

They’re light green and about a half to three-quarters of an inch long. While a couple are no big deal, a larger infestation can stunt your plant’s growth.

A strong spray of water will knock them loose and the little pests won’t climb back up onto the plant.

If you still have problems, you can get a product that contains Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki (Btk) and follow the manufacturer’s directions.

Read more about using Bt to control pests here.

Scale

Rose scale (Aulacaspis rosae) is a small bug that attaches itself to leaves, branches, canes, hips, and blossoms, and feeds on sap.

The adults have waxy shells and don’t move, so they often get mistaken for a disease rather than an insect.

The nymphs are orange and move around until they find the perfect spot to hunker down. If your garden is infested with enough of them, they’ll cause plants to look stunted and generally unhealthy.

Bonide Pyrethrin Garden Insect Spray

You can scrape the bugs off stems or use an insecticide containing pyrethrum to get rid of them, like this one from Bonide that’s available on Amazon.

Snails

In the grand scheme of things, snails are the least of your concerns when growing roses.

The common brown garden snail (Cornu aspersum) may attack immature foliage and can destroy young seedlings, but older plants are generally immune to serious damage.

Use pet and child-friendly slug pellets or traps if you need to control a large infestation.

Learn more about how to control slugs and snails in our guide.

Spider Mites

These tiny arachnids from the genus Tetranychus can drive a gardener bananas.

Depending on the severity of an infestation, despite their small size, mites can not only make your plant look stunted and unattractive, but they can actually kill off a tender plant entirely.

These spider relatives thrive in hot, dry weather. You’ll rarely spot the bugs themselves, but the damage that they cause is obvious. You’ll often see fine webbing that they leave behind, and the leaves will be stippled with yellow spots.

You can blast your plants with a strong spray of water to knock them loose, but I find that this only works in the case of a light infestation.

For a more severe problem, use neem oil, insecticidal soap, or a miticide to control these pests.

Thrips

Rose thrips are so tiny that you wouldn’t even know they were there, except for the fact that they can do serious damage to your rose bushes.

There are several varieties that will attack your flowers, including chili thrips (Scirtothrips dorsalis) and Western flower thrips (Frankliniella occidentalis).

Thrips cause buds to look distorted or they won’t open. You may see bronzing on the edges of foliage, followed by leaf drop and complete defoliation.

The amount of damage they can cause is seriously surprising, given how small these insects are.

The best way to control these pests is to head outside and check your roses every day. I like to look at this as a relaxing stroll through the garden rather than a chore.

Cut out any developing buds that look distorted or bent (like the one in the image above), trimming down to a five-leaf leaflet.

Remove any damaged leaves and clean up all fallen leaves at the base of plants.

Disease

We have a wonderfully helpful guide for dealing with rose diseases, so I’ll just briefly touch on what to watch for here.

In addition to the following, you should also watch out for botrytis blight, cankers, crown and root gall, and rose rosette disease.

Black Spot

Familiarize yourself with this disease, because chances are high that you’ll run into it eventually.

As the name implies, it causes black spots on the leaves. Black spot can stunt plants’ growth and cause leaves to drop as well.

It’s caused by the fungus Diplocarpon rosae. There are a variety of fungicide sprays you can use to tackle the problem.

However, note that repeated use of a fungicide can result in the fungi developing resistance. It helps to rotate the type you use.

Rust

Rust is another common fungal disease that often appears as rust-colored marks on leaves and canes.

Powdery Mildew

Powdery mildew attacks not just roses, but a ton of other types of plants as well. It looks like plants have been dusted in a white powder.

You can apply a 50:50 mix of water and milk to your roses if the infestation is mild, with only a few leaves impacted.

Otherwise, you’ll probably need to turn to fungicides.

Learn how to treat powdery mildew in this guide.

Best Uses

Roses can be utilized in so many different ways.

They make good barriers as hedges, are stunning specimens in an ornamental garden, or can be grown as climbers to cover walls, pergolas, and fences.

There are varieties that make good ground covers, and types that are ideal for a container garden.

The flowers can be cut for fresh bouquets, dried, or preserved in wax. The petals can be used in potpourri, sugar scrubs, creams, and lotions.

They can be used to make rose water, tinctures, and teas, or enjoyed fresh in salads or desserts. You can even make sugared rose petals with this recipe from our sister site, Foodal.

A Note of Caution:

If you decide to eat your roses – and you should, if you ask me – keep in mind that you should not consume any that have been treated with fungicides or pesticides before harvesting.

Always read the label of anything you use to care for your roses, apply according to package directions, and only treat plants in the garden as edibles if they have been grown as such.

The hips, which are high in vitamin C, can be turned into tea, jelly, syrup, soup, or sauce, or dried and ground into a powder to make a supplement for humans and livestock.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Perennial flowering shrub | Flower/Foliage Color: | Red, pink, white, purple, yellow, orange, peach, lavender/green |

| Native To: | Asia, Europe, North America | Maintenance: | High (depending on variety) |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 3-11 | Soil Type: | Organically-rich loam |

| Season: | Spring-fall | Soil pH: | 6.0-6.5 |

| Exposure: | Full sun to partial shade | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | 2 feet, depending on variety | Attracts: | Bees, butterflies, hummingbirds |

| Planting Depth: | Bury bud union/knot above roots (seeds 1/4 inch) | Companion Planting: | Basil, dianthus, foxgloves, geraniums, lavender, mint, speedwell, tomatoes, violets, yarrow |

| Time to Maturity: | 3-5 years | Avoid Planting With: | Ivy, honeysuckle, morning glory |

| Height: | 1-20 feet, depending on type | Uses: | Hedges, specimens, cut flowers, drying, preserving, culinary use |

| Spread: | 1-20 feet, depending on type | Family: | Rosaceae |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Genus: | Rosa |

| Tolerance: | Heat, part sun, drought, frost (depending on variety) | Species: | Centifolia, chinensis, damascena, multiflora, rugosa |

| Pests & Diseases: | Deer, rabbits, squirrels; aphids, cane borers, Japanese beetles, sawflies, scale, snails, spider mites, thrips; black spot, botrytis blight, brand cankers, brown cankers, crown gall, powdery mildew, root gall, rose rosette, rust, stem cankers |

Now You’re Ready to Become an Official Rosarian

Growing roses isn’t the easiest hobby to jump into, but don’t overthink it.

These are, after all, just plants. If something goes wrong, you can always try, try again.

And if you follow the tips in this guide, I have full confidence that you’ll be enjoying abundant blossoms in no time at all.

If you take anything away from this article, I hope it’s that selecting the right site and the right type of rose is key, and you will need to be prepared to dedicate yourself to doing a little maintenance.

But that’s not much different than what’s required to care for any other plant, right?

Are you inspired to grow roses in your garden? Let us know in the comments section below!

And for more information about growing flowers, check out these guides next:

Photos by Kristine Lofgren © Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Product photos via Bonide, CowPots, Great Big Plants Store, Neptune’s Harvest, and Taunton Press. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock.

About Kristine Lofgren

Kristine Lofgren is a writer, photographer, reader, and gardening lover from outside Portland, Oregon. She was raised in the Utah desert, and made her way to the rainforests of the Pacific Northwest with her husband and two dogs in 2018. Her passion is focused these days on growing ornamental edibles, and foraging for food in the urban and suburban landscape.