[ad_1]

On the upper floor of CoCA, a propositional architectural drawing floats through three spaces of the gallery. In the largest space, there is an enormous mechanical arm, tethered to the wall by its elbow. It moves in slow and deliberate arcs across the room, sweeping back and forth over the floor as if carefully searching for a lost contact lens. It knows it lost it somewhere along this line but it’s so dark…

It hums a mechanical tune as it searches.

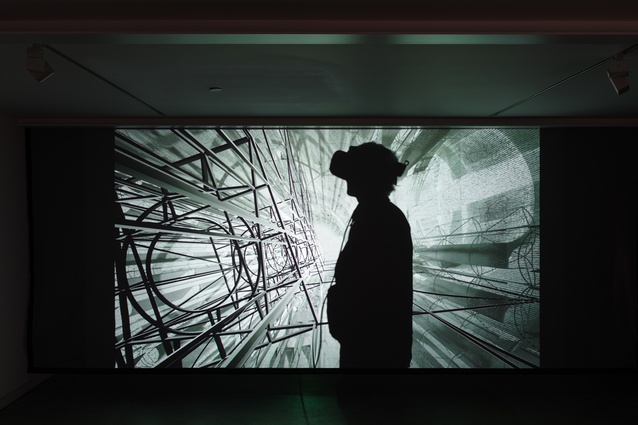

In the second, smaller space, the drawing becomes virtual. A VR environment shows the mechanical arm in accurate virtual fidelity, searching away. The arm suddenly begins to play up. It replicates itself, tilts and flies around, freeing itself from the slow plane of the floor and drawing dynamic spherical forms in virtual space. These swirl around as patterned screens, composed of a spider’s work of lines, which curve around and through one another, interrupting beams of light, and spawning more and more lines, screens and shadows. The mechanical hum rises to a crescendo.

Simon Devitt

The third part of the drawing is a short film. A person, Kari, is trapped in a gallery space, becoming increasingly anxious as she encounters duplicates of her mobile phone, her water bottle, then herself. She searches for a way out, only to discover replications of herself and her personal objects again and again. She discovers the gallery has become a closed container, rhythmically looping her back into an internal cinematic world.

This fascinating experience is the work of Aaron Paterson, Sarosh Mulla and Marian Macken, in collaboration with Fabio Morreale, Clovis McEvoy, Xiaoling Cheng, Brendan Donovan and Kate Elliott, who provide the sound, music, digital and cinematic backup. Drawing Room is part of Paterson, Mulla and Macken’s hybrid practice, which looks at drawing’s often torrid relationship with architecture.

It follows research from the three, individually and in collaboration, exploring drawing devices, such as the Claude glass (Penumbral Reflections), the role of the body in drawing (Drawing within the Room), drawing as spatialised books (Binding Space) and post-digital architectural practice (PAC Studio buildings). Their work is part of a rich legacy of thinking about architectural drawing in Aotearoa.

I am highly susceptible to the wonderful hovering, questioning feel of this project. I like the way it folds back on itself, squeezing through contorted portals from one representational realm to another; real space moves to virtual where it expands to vast, abstract scale, then closes down to the intimacy of a water bottle flung across a floor. I enjoy having the show enclose me in a contained loop of propositional architectural drawing.

Architectural drawing is shackled to the physical world. It organises future space, at the same time as predicting its unmeasurable qualities. This mix of reality and imagination makes drawing an important tool for research, with the capacity to distil things at the cusp of awareness, even while describing built space.

Drawing Room is part of this world of drawing as research. It pursues a shadowy architecture that ‘always remains at the edge of its own explicitness’.1 It does this by deliberately messing with connections between the built world and drawing. The exquisitely detailed and fabricated drawing arm, which clearly follows a great deal of careful digital drawing, is also the beginning point for an explosion of drawings in the VR environment. These create dynamic virtual architectures, with real space becoming ‘an abstracted fiction’.2

Despite being the most built thing in the show, the arm is contented to draw a pentimenti of rubber tyre tracks and shadows on the floor, while its avatar goes nuts in the virtual world, joyfully scribing a complex, three-dimensional architecture. The drawing machine seems a red herring or decoy: a kind of ‘echo object’3 that keeps secrets as to where architecture is within this shapeshifting, shadowy drawing world.

I asked it to reveal them but it didn’t answer; it just calmly paced back and forth, searching and re-searching.

[ad_2]

Source link