[ad_1]

Started in 2011, when its two founders, Milinda Pathiraja and Ganga Rathnayake, returned home to Sri Lanka after ten years of studying and working in Melbourne, the Colombo-based Robust Architecture Workshop (RAW) is a veritable enfant prodige in the architecture sector. Over the course of its as-yet brief existence, the office has produced a remarkable collection of work, perhaps not by quantity (eight buildings completed and eight currently in development or under construction) but certainly in terms of professional acknowledgement and, hopefully, cultural influence.

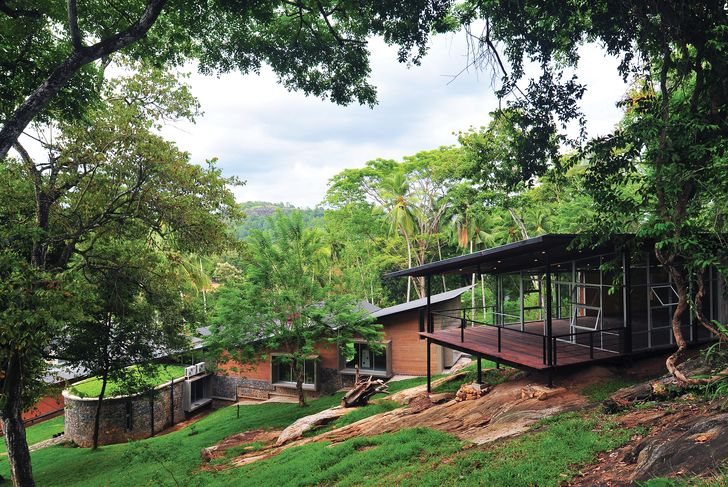

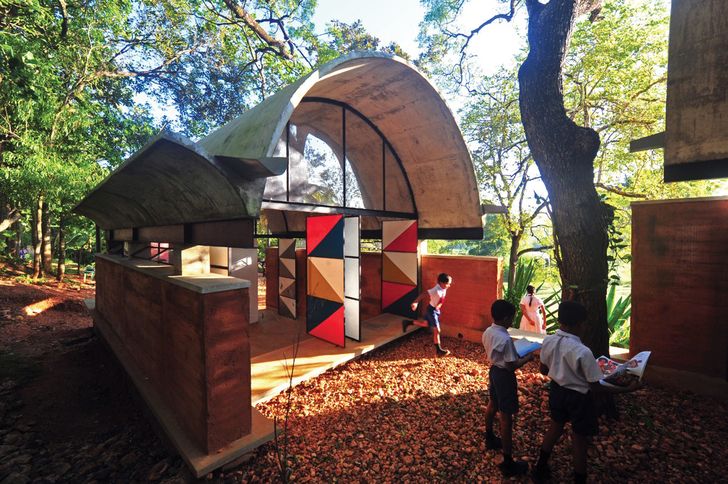

In 2014, RAW entered the Lafarge Holcim Awards with its design for a community library in a former military camp in Ambepussa, at the centre of the island country; it won the Bronze Award for Asia Pacific that year and a Global Silver Award in 2015. Ever since, the practice has been collecting one accolade after another, including a 2016 Terra Award (an international prize for contemporary earthen architecture) for the same building. House 412, a single-family dwelling in the Colombo suburb of Kottawa designed in collaboration with Pulina Ponnamperuma, won the 2018 Australian Institute of Architects’ International Chapter Award (Residential Houses – New).

RAW’s design for a community library in a former military camp in central Sri Lanka won a Lafarge Holcim Award, the first of a string of accolades for the practice.

Image:

Kolitha Perera

While the architectural quality of RAW’s built projects alone could well justify the level of distinction it has achieved and the interest it has raised among the profession, it is something less obvious and more fundamental – and connected to Pathiraja and Rathnayake’s Australian experience – that may be worth highlighting. I am referring to the very particular approach to design that RAW developed before getting into formal practice, and which it has been perfecting ever since.

The seed is to be found in the PhD in architectural design completed by Pathiraja at the University of Melbourne in 2010 (incidentally, under my supervision), with a title that would eventually resonate in the name of the office: “The idea of ‘robust technology’ in the definition of a ‘third-world’ practice: architecture, design and labour training.” The idea behind the “idea” in the title was simple and yet ridiculously ambitious at the same time: architects in fast-urbanizing economies can contribute to the evolution of the building industry in which they are embedded by strategically detailing, at project level, construction systems and solutions capable of inducing a natural process of vocational training for the unskilled workers that make up the labour force, enabling them to move across the industry and infuse it with appropriate craftsmanship.

A collaboration between RAW and Pulina Ponnamperuma, House 412 gave bricklayers as well as other construction workers the opportunity to practise a variety of techniques.

Image:

Kolitha Perera

If Pathiraja’s doctoral dissertation proved successful academically (it gained the Royal Institute of British Architects President’s Award for Research in 2011), it was the proposition informing it that would eventually give physical shape and social relevance to the raw talent of RAW: buildings can be thought of as micro-laboratories in line with a radical notion of “industrial design,” where form and materials provide the opportunity for specific types of socio- technical development.

Indeed, each building produced by RAW testifies to the validity of this thesis. The perimeter of House 412 is an ode to didactic variations in bricklaying patterns; the library in Ambepussa (2015) lines up welding connections and rammed earth techniques to train the soldiers who will soon become civilian – and most likely construction – workers; a department store in Colombo (2015) incorporates in situ concrete-forming alternatives in a country being built with cement; a demountable chalet in the tea fields of Madulkelle (2016) tests light-steel prefabrication systems that would allow artisan journeymen to work from their villages; two primary-school reading rooms in Dewahuwa (2018) experiment with rammed earth and ferro-cement as materials with which the parents of the schoolchildren can learn to work as they contribute to the project.

In spite of the undeniably high level of design resolution, the formal and technological variety displayed by these and other works suggests that specific association with any particular architectural language is considered to be of relatively little importance in the practice of RAW compared to, say, the ethos underlying its professional routines: the building industry is vital to the future of any country and architecture must be a vehicle and an arena for construction workers’ improvement. This requires an acceptance of technical errors in execution, which, in turn, requires the industry to embody robustness in its conceptual scaffold and operational boundaries.

The workforce for the construction of two reading rooms at a primary school in Dewahuwa were largely parents of the schoolchildren; the design and building systems enabled them to upskill while constructing a quality building.

Image:

Kolitha Perera

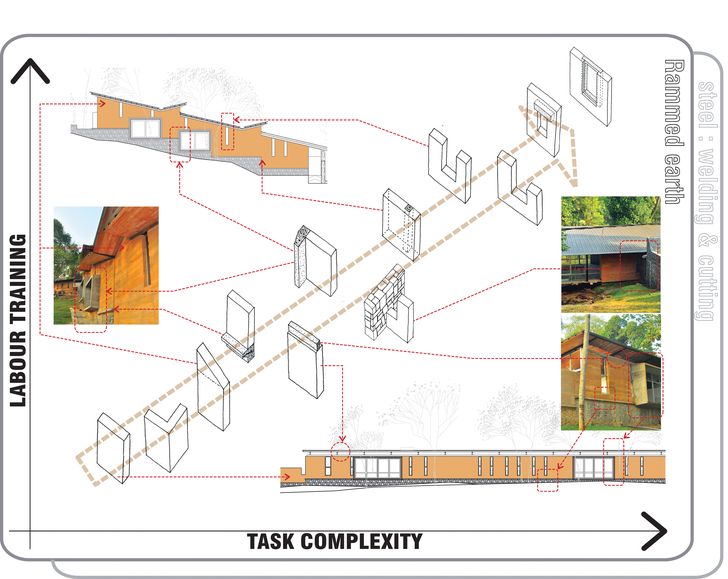

Notwithstanding its infectious power, the maintenance of such a refreshingly explicit ideological vision cannot rely simply on enthusiasm. Rather, it needs scholarly application, empirical research and, ultimately, critical reflection. The artefacts betraying RAW’s discreet investment in the ideological dimension of practice – too often vaunted with little substance on architectural firms’ website slogans – are the material charts prepared for each project, with task complexity on the horizontal axis and labour training levels on the vertical axis. The technological progression suggested on the diagonal plane becomes a compass for the work and a gauge for the decisions taken – decisions exemplified by another set of drawings describing fabrication and site-assembly procedures, or the process to undertake.

A review of RAW’s work from this process perspective may result in the realization that buildings, in architectural practice, can be treated also as means rather than just ends. Buildings can generate precious opportunities for others beyond the boundaries of the practice; these opportunities are only made possible, however, by the ability of the profession to think of and cast itself as an agent of change at a different and broader level.

RAW’s dedication to empirical research and critical reflection is evident in the material charts (such as this chart for rammed earth) that it prepares to guide the work on each project.

It goes without saying that the use of architecture as a de facto industrial policy vessel is a function of the context in which one operates and the level of maturity of the local industry. Acting RAW in urban Australia may be more difficult than being RAW in urban Sri Lanka. Nevertheless, the history of the office and the proven effectiveness of its philosophy, architecturally and otherwise, can be used to highlight a series of issues at the core of any contemporary profession.

The first is the intellectual potential generated by the organic integration of professional practice and research method. The work of RAW has been drawing on both by using design as reciprocal knowledge translator as well as amalgam. In doing so, the office has been able to establish a clear culture of practice, transmissible and shareable within its walls, that has moulded a very young group of architects and interns into a cohesive technical outfit intellectually at ease with the challenges and the opportunities of the locale. Ultimately, this could suggest a possible transformation of the long-established meaning of “critical regionalism” and the subject matter at its core, focusing less on work within the interstices of practice, as per Kenneth Frampton’s implication in his discussion of architectures of resistance a quarter of a century ago, and more on action across the practice’s whole territory. If there is a message in the buildings of this young, revolutionary firm, it is that “architect” does not need to remain a noun alone; it can also be a verb – “to architect,” or to establish relationships, via buildings but also beyond them.

[ad_2]

Source link