[ad_1]

The afternoon we were waiting for the doctor to call with the results, my father, an architect, asked me to sluice clay from the duck pond on the front of his property. The one fringed with poplar trees, their winter-ruined branches skeletons guarding the murky brown water.

He didn’t look up as he spoke. He was urgent for the first time in weeks. Bent over his drawing board, his greying seabird’s-nest curls – the ones his mother loved, a halo – flecked the gold of his youth again in the slanting late afternoon light. His roll of translucent paper was stretched over the top of his plan, tacked down at the edges with masking tape. Between his fingers was his pencil stub – the only pencil I’ve ever seen him use, 4B, never quite sharp. He was carving with it now – soft, scooping circles. Beside him a jar of black and red pencil stubs, some used down to the bone.

He was standing, slippered feet planted on the bare wooden floor, chair pushed back, bent sideways over his drawing board, the ruler pushed askew, unnecessary. He hadn’t stood like that for what felt like weeks, either.

When he asked me to dig the clay he knew two things: the pond was inside the fenced-in duck run and I had a fear of ducks (really, even as a grown adult the panic-beaty-heart starts when they get too close); and also, I hate touching clay.

It must be soft, wet. I would know what to do, he said.

And he was right. Despite not wanting to know how to prepare clay, despite wilfully ignoring his patient teachings over the years, I did know how to scoop clay from the soft edges of the pond, wet and whisk it in a bucket, soften it till it was the right consistency to work into shape.

Before I said yes to the clay – we both knew I would – I asked him why. His pencil paused mid-swoop, hovered for a moment in the air towards me, like he might tell me then, but instead just waved me away. I put his gumboots on, far too big for me but waiting as always at the door, then went into the cold.

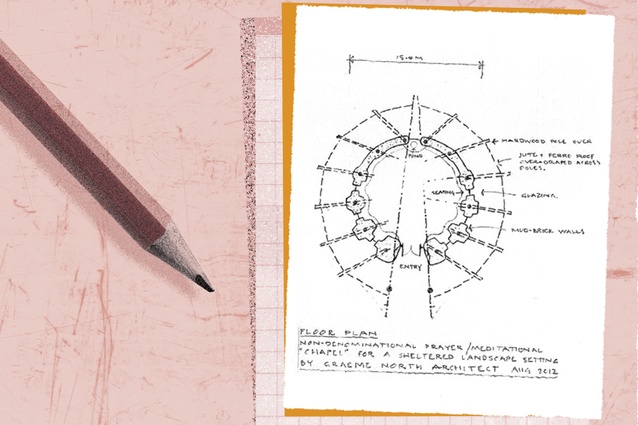

Later, when he wasn’t in his office, I snuck a peek at his plans, running my fingers lightly over the thick pencil lines. A circular earth building, of course. It was so clearly one of his – I would have known that anywhere – but this didn’t look like the houses he usually designed. It looked vaster, and it was open, just one large curving room winged in windows with a high, open door.

“What is it, Dad?” I said when he came back, caught me looking.

He took the bucket of clay. “A place of worship. A chapel.”

“Really?”

“Yes.” He sat down, dipping his hands into the bucket.

“You’re not –”

“This isn’t about that. This doesn’t align to any religion.”

“Chapels like that don’t exist, Dad.”

He came up with a lump of clay. Whacked it down onto the drawing board, winked. “Nothing ever does until it’s built.”

Quiet, standing to the side of his workbench, out of his light,

I watched him work up handfuls of the clay I’d collected, the way I used to as a child, sneaking out to the shed tacked on to the side of our house, his ‘office’, the one he’d built on to our converted bach by the sea, fitting it with barn doors he’d ferreted from somewhere, once used to keep the horses in, or, in his case, keep us kids out – we couldn’t open the high, heavy door on our own.

I was just tall enough to peer over the top of the bottom door, see him leaning into his drawing board, a pencil dangling from his mouth like a forgotten cigarette, or if he wasn’t there, sitting back in the shadows, hunched over his wheel making pots. I watched him now, old potter’s fingers stiff, but adept still, scooping out handfuls of clay to let the light in. I watched him fit small pieces of balsa wood and twigs to make the rafter roofs, where he, I guessed, would lay paper or soft cloth, sweep fine layers of clay or plaster over the top, settling like a blanket rumpled over the hills, creating a tiny copy of his signature ferro cement style.

“That’s the phone, Dad.”

“So it is, sport.”

He didn’t move from his work. He ran his fingers over the wall he was working on. The whole thing was around 80cm in diameter. Made of mud and sticks, a bird’s nest. Feather light. Fragile.

The phone stopped mid-ring, my stepmother answering it in another room. Light years away.

“I didn’t know you were working on a building,” I said. She would be walking towards us, here in his studio. Each second a time bomb.

“I wasn’t,” he said. Then he turned, looked at me. “I woke up today and it was just… there… floating… complete… just like that!” He let out a short unexpected laugh, a flare of joy. “Right there!” he said. “In 40 years of architecture. Never… not like this.”

Then the phone was in his hand. I left the room.

When the phone was safely back in its cradle, I went back. His hands were on the roof now, layering down half the roof; on the floor he’d drawn a curving tile pattern on paper. He tacked it down.

“They want to operate,” he said. “Monday.”

I did the maths – three days.

“I told them I’m working. I need more time.”

“But –”

“I need more time.”

Later, he told me about the commission. An elderly, well-off local artist, a man who had made his name as a potter, wanted to leave a legacy in the area, something truly special that would bring people to the region to visit. It would be a place of worship, but not to any god – simply a homage to beauty, kindness, nature. It would bring people together, all people; it would be something this man who had enjoyed much artistic success in life could leave behind.

It sounded exactly like the kind of thing my father would like to leave behind, too.

My father was lucky – he got more time. And then he got the years after that, too. He finished the model, the plans drawn and finished before they wheeled him away for the operation. He spent long weeks recovering. Spring came. By the end of the summer, the artist’s children discovered what he was planning to do with their inheritance money and the project was off. Dad rolled the plans up tight and stuffed them in a tube. Put the model on a high shelf to gather dust. He mostly retired. That was the last time I saw him draw like that.

I think about the building often. It’s a question mark, an incomplete story. And it’s something you don’t often consider when you think about architecture and the way architects give their life to their designs – you think about what they make. It’s such a tangible thing; there is an outcome to the design process, a building that lives and breathes and shelters and dilapidates over time and is patched, altered, repaired, lived in, loved, torn down. But you hardly ever think about the unborn buildings, those promises, those dreams.

For a long time afterwards, I believed that the project would come back – the children would have a change of heart, or the artist would just do it anyway. How could something that came to my father like that – like a gift from a god he doesn’t believe in – come to nothing? I want it to make sense, to have an ending, but it refuses it.

This chapel, this building, will never exist. And yet, I long to go there. I long to walk into the light-filled space as my father described it to me that day, and I could feel myself walking under the gilded cardboard copper archway, down the warm tile floors, see the flowers growing in the inside gardens as he walked me through the details, feel the light on my arms as I passed the vast windows. I long one day to have the money, land, time, to unroll those translucent plans, buttery with age but still distinct with my father’s signature pencil scrawls, spread them on a table before someone more gifted than I, and ask them to make it into reality; I will ask them to build it.

This essay is available in the Te Kahui Whaihanga New Zealand Institute of Architects publication, 10 Stories: Writing about architecture / 6, which can be purchased from their shop.

[ad_2]

Source link