In 1911, when Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin learned of the competition for the Canberra Plan, Australia was seen all over as one of the world’s most democratic countries. It was the second country, after New Zealand, to allow women the vote and to stand for parliament.

“Post federation, they saw Australia very much as the blank slate – a new world with the beginning of a great and very humanity-driven democracy,” said Anne Watson, author, curator and architectural historian, who will be delivering the Marion Mahony Griffin lecture in Canberra on 13 March.

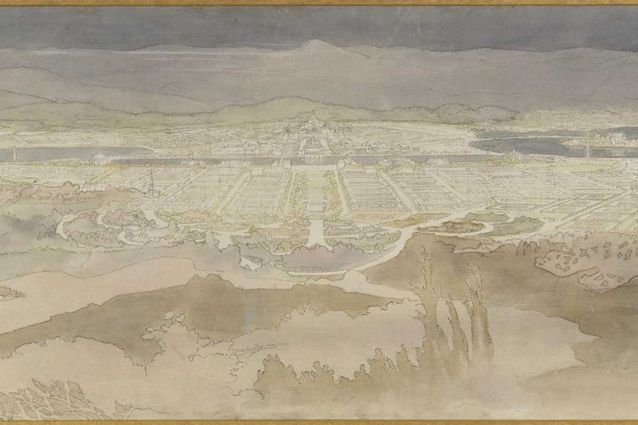

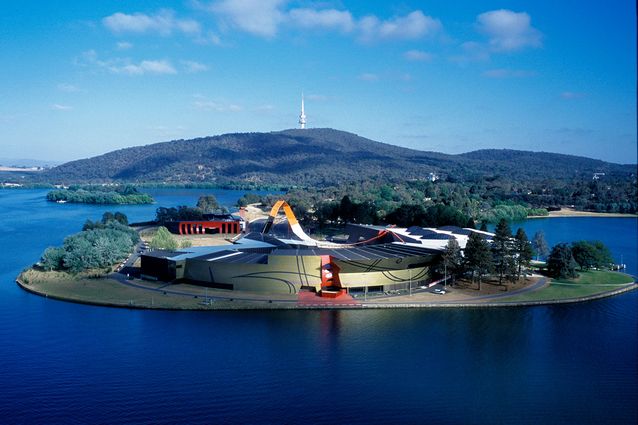

The Griffins’ Canberra Plan was “laid out according to democratic principles but also according to the natural environment – the surrounding hills, the way they enveloped the city and still do,” Watson said. “Using those vistas was very important as well as using the lake as an area for play and recreation.”

According to author Glenda Korporaal, who wrote the first biography of Marion Mahony Griffin, it was Marion who had convinced Walter to enter the Canberra competition. It was also Marion’s exquisite drawings that had clinched them victory in the competition.

For more than a century, Marion’s role as “a founding mother” of a city has been in the shadows of her male partner, but in a year that marks the 150th anniversary of her birth, there is renewed focus on her life’s work and legacy. Sydney Living Museum’s Paradise on Earth exhibition, curated by Anne Watson, and the National Capital Authority’s Magic of Marion’s series of events seek to pay tribute to a world leading female architect.

“Her artistic stills were extraordinary, as an architectural renderer, but as an artist as well,” Watson said. “There was a spiritual dimension as well. Her drawings, her artwork and her architectural renderings, have this lovely, lyrical respect of the natural world.

“The forest portraits were these lovely tree studies she did in watercolour and dyes on silk [from her bushwalks in Tasmania and Victoria] tell us about her spiritual connection to nature and her extraordinarily evocative artistic skills.”

Watson said Marion was a great environmentalist and had been active in environmental groups in Chicago before moving to Australia.

“She and Walter brought those ideas to Australia, falling in love with the Australian landscape and in particular the Australian flora. They were very vocal in promoting the use of native plants in landscape architecture, as well as home gardening. Rehabilitating the bush, respecting the bush, all those things that we still talk about now but they were really vocal about it more than 100 years ago,” Watson said.

The Griffins’ vision for Canberra was stonewalled by bureaucracy and, in 1920, an opportunity arose to buy land in Sydney’s Middle Harbour and the couple jumped at the chance to create their own utopian suburb that is now Castlecrag.

“They had dreams of living in Sydney and living in a sustainable, community-driven existence in this utopian suburb,” Watson said. “What they did at Castlecrag is design houses that use local materials, that were fairly modest and took advantage of views but didn’t impinge on neighbours’ views, that fitted into the landscape. Roadways were contoured to fit the topography, rather than a right-angle grid imposed onto the landscape, and a system of reserves and walkways [was created] to encourage interaction with the community.

“All these things are the kinds of things that we recognize today as being very important and they recognized then as being very important, but weren’t happening elsewhere in Sydney and still aren’t happening in Sydney.”

“Castlecrag is the beautiful, desirable suburb it is today because of the foresight of the Griffins in laying it out the way they did.”

After Walter died in India, Marion returned to United States where, towards the end of her life, she was destitute and fell into relative obscurity, when Walter’s name continued to be credited for their combined work.

“She revered Walter all the time,” Watson said, “She thought so highly of him that I think she was fairly content to stay in the background.

“Even though she was a very forthright and outspoken person about issues. On the issue of women’s rights, she was probably content with the fact that she had been able to graduate as an architect at a time when that was highly unusual for a woman and that she was able to practice as an architect and an artist, both of which she loved.”