[ad_1]

As if there aren’t already enough diseases to worry about when you’re growing tomatoes, add Septoria leaf spot to the list.

This can be one of the most destructive diseases of tomato plants, and it is a particular problem in areas prone to extended periods of wet, humid weather.

Both Septoria leaf spot and early blight manifest as spots on the leaves, but it is easy to tell them apart if you know what to look for. We’ll help you to do this, so you can determine which plan of action to take.

Neither your greenhouse seedlings nor your full-grown plants are safe from Septoria, and this fungus can strike at any stage of development.

Here’s everything that you will find in this guide:

Septoria Leaf Spot Symptoms

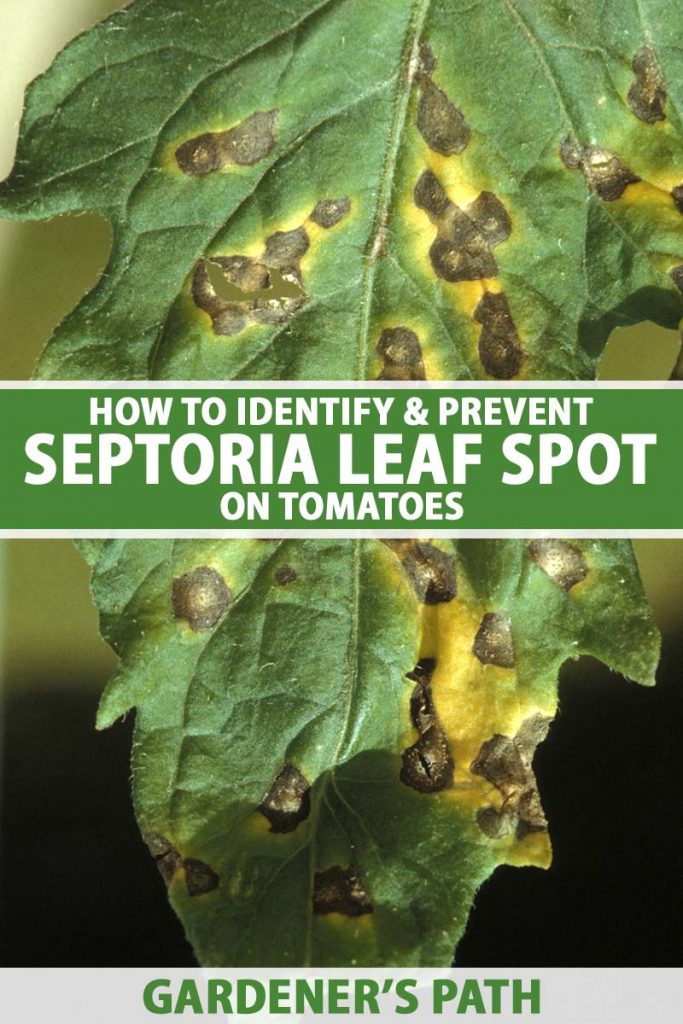

Small spots on the lower leaves of your tomato plants will be the first indication that they are infected with this fungus.

If infected, the undersides of the leaves will have many small, water-soaked spots that are about 1/16 to 1/8 of an inch in diameter.

These spots will have a dark brown margin and gray or tan centers. The lesions may merge together into larger spots as they mature.

Mature lesions will have a lot of dark brown structures in their centers that look like flecks of black pepper.

These pycnidia are the fruiting bodies of the fungi that produce the spores, and they are visible to the naked eye.

This fungus rarely infects the fruit, which remain edible, although it can cause spots on the stems, blossoms, and calyxes.

Leaves that are heavily infected will turn yellow before drying up and dropping off. Splashing water can cause the disease to spread upwards to the youngest leaves and infect them.

Sometimes the number of leaves lost is so high that the fruit may be scalded by the sun.

How to Tell Septoria Leaf Blight from Early Blight

Aside from the fact that early blight usually strikes early in the season, there are two key ways to determine whether or not an infection is caused by the fungus Septoria lycopersici.

Early blight lesions will not have visible pycnidia in them, so if you see the black spots, it is likely that your tomato plants are infected with Septoria.

The lesions caused by Septoria lack the classic bullseye that is found in early blight lesions.

Learn more about early blight in this guide.

How the Disease Spreads

In temperatures ranging from 59 to 80°F, the pycnidia exude numerous spores.

Splashing water is a common way for these spores to spread, but tools, insects like beetles, and even your hands and clothes can spread them.

If conditions are moist and favorable, your plants can be fully infected within two weeks.

The spores can germinate within 48 hours, leaf spots can develop in as little as five days, and pycnidia appear within seven to 10 days. The fungus can produce more spores within 10 to 13 days.

However, the spores cannot infect the plants unless free moisture is available, so infections are more likely on rainy days or in areas with long-lasting dew.

A number of plants in the nightshade family are vulnerable to infection by this pathogen and serve as potential hosts. There, they are able to produce even more spores that can infect tomato plants.

These include garden crops such as potatoes and eggplant as well as common weeds like nightshade, jimsonweed, horse nettle, and smooth ground cherry.

The pathogen cannot overwinter in the soil by itself – it requires plant debris to do so.

Solanaceous weeds can often live through the winter as well, and harbor fungi that can infect your tomato plants as soon as conditions are favorable.

Cultural Control Options

There are many different steps you can take to control this disease, and most of them involve getting rid of the initial sources of the spores.

Unfortunately, no fully resistant cultivars are available currently, although ‘Iron Lady’ is partially resistant.

Remove Diseased Leaves

If you catch an infection early, you may be able to stop it by removing the lower leaves that are infected and burning or destroying them.

Do not put them in your compost pile!

Remove Susceptible Weeds

Be vigilant about removing susceptible weeds that are growing in or near your garden or field.

Mulch Around the Base of Plants

Mulching your plants will reduce the chances of having spores spread via splashing soil, which can contain a mixture of spores and plant debris.

You should wait until after the soil has warmed to 70°F before adding mulch.

Do Not Water Overhead

Using overhead irrigation will greatly increase the chances of infection. To avoid this fate, water early in the day, and use a soaker hose at the base of the plants.

Promote Good Airflow

Promoting good airflow will enable the plants to dry more quickly after they get wet, lessening the chances that any spores that are present will be able to germinate.

Staking your plants will lift them off the ground and allow air to blow through.

Pruning and removing the lowest leaves can also help to thin the plants, enabling the remaining leaves to dry more quickly after they get wet.

Remove Plants at the End of the Season

If you have a garden, you should remove the plants and dispose of them at the end of the season. If you grow your plants in containers, you should sterilize all pots before using them again.

If you are growing your tomatoes in a field, plow the plants deeply under, so the tissue cannot serve as a source of spores. The plant tissue must decay completely, or it will carry the fungal spores over to the next season.

Rotate Crops

It is always a good idea to rotate where you grow your tomato plants, because so many disease pathogens can persist in the soil.

If you battled Septoria leaf blight, you should wait two to three years before growing any solanaceous plant in that location again.

Disinfect Stakes and Cages

This fungus can even survive the winter on your stakes and cages in warmer climates, so be sure to disinfect them if you will be reusing them.

To do this, you can spray them with 70 percent rubbing alcohol. Dipping them in 10 percent bleach is another option, but be careful to rinse them off thoroughly, because bleach can damage your plants.

Fungicide Treatments

If your plants are severely afflicted, you have the option to use fungicides. They will not cure leaves that are infected, but they can stop the infection from spreading further.

Most of the fungicides that are commonly used on tomatoes will work against Septoria leaf spot.

Bonide Fung-onil Concentrate

One recommended and commonly available product is Bonide Fung-onil Concentrate, which you can find at Tractor Supply Co.

If you are looking for an organic fungicide, the classic Bordeaux mixture is always an option.

This is a mix of copper and sulfur that has been used to control fungi since the 1800s.

Bonide Copper Fungicide Dust

Arbico Organics offers Bonide Copper Fungicide Dust – an updated formulation of Bordeaux mix.

Starting at the first sign of infection, apply these chemicals at seven- to ten-day intervals throughout the season.

Check the leaves regularly to make sure there are no visible spots. This will let you know that the fungicide is working.

Fungi frequently develop resistance, and you may need to switch to a different class of fungicide.

Take Action Quickly If You See These Spots

While it is possible to nip this infection in the bud, Septoria leaf spot can be a serious problem if you grow tomato plants.

The fungus does not usually infect the fruit, but an infection may result in poorly developed tomatoes, and it can ruin your crop.

Applying a number of cultural controls can help to prevent infection. However, if this disease strikes your plants despite your best efforts, you may need to use fungicides to keep it under control.

Have you encountered this disease? Were you able to save your plants? Let us know in the comments section below.

And for more information about pests and disease that can affect your tomato plants, check out these guides next:

About Helga George, PhD

One of Helga George’s greatest childhood joys was reading about rare and greenhouse plants that would not grow in Delaware. Now that she lives near Santa Barbara, California, she is delighted that many of these grow right outside! Fascinated by the childhood discovery that plants make chemicals to defend themselves, Helga embarked on further academic study and obtained two degrees, studying plant diseases as a plant pathology major. She holds a BS in agriculture from Cornell University, and an MS from the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Helga then returned to Cornell to obtain a PhD, studying one of the model systems of plant defense. She transitioned to full-time writing in 2009.

[ad_2]

Source link

+ Planting String of Watermelon Succulents

+ Planting String of Watermelon Succulents  with Garden Answer

with Garden Answer