[ad_1]

Marrubium vulgare

Like many people, my first experience with horehound was crunching down on a hard brown candy that my grandpa bought me from a jar at an old fashioned candy shop.

I remember thinking it tasted a bit like a sad version of root beer candy.

Despite our inauspicious start together, horehound has become a must-have herb in my garden.

That’s because, besides being an essential ingredient in making the candy (which I’ve grown to love), it’s one of those plants that gives more than it takes.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

In arid gardens where other plants flounder, this mint relative cheerfully keeps doing its thing. It also attracts beneficial insects and deters the bad bugs, which is a life-saving benefit for the rest of my garden.

Plus, it has been used for centuries to ease coughs, indigestion, and colds. It can also be used in cocktails, to flavor beer, or even as a seasoning.

If you can’t wait to get your hands dirty, here’s what we’ll cover in the upcoming guide:

Get your gardening gloves ready and let’s dive in!

Cultivation and History

Horehound is a perennial herb that is sometimes called common, white, or woolly horehound, marvel, or houndsbane. It’s sometimes spelled hoarhound.

The name isn’t a reference to the Egyptian deity Horus, despite what some sources claim. Instead, it’s likely a derivative of the Old English word horhoune, which means hoary or hairy.

Native to Europe, North Africa, and Central and Western Asia, it was brought by European invaders to – and has since spread and naturalized in – North and South America.

It has also spread throughout southern Africa, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan. It grows best in USDA Hardiness Zones 3-9.

Horehound belongs to the Lamiaceae family, which includes mint, pennyroyal, sage, basil, and oregano. Don’t confuse Marrubium vulgare with scallop shell horehound (M. supinum). The latter is often just called horehound, but they are different plants.

This herb has been around a long, long time. It was used in ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome, and was particularly popular during the Middle Ages in Europe.

It has also been a part of traditional Chinese, Australian aboriginal, and ayurvedic medicine. Historically, it has been valued as an expectorant, cough remedy, and as an effective way to treat colds, lung ailments, and skin issues.

It’s still valued for all of these purposes today in modern cultures around the globe. Horehound is an expectorant and people use it to relieve coughs, loosen mucus, increase the flow of saliva, and stimulate the appetite.

The jury is still out on whether or not science can back up its medicinal claims to fame, however.

These days, it’s commercially cultivated across the world, but primarily in France. On top of its medicinal uses, many people have used and continue to use it as a flavoring for beer, candy and tea.

Speaking of candy, don’t pluck the leaves and take a bite expecting the delicious licorice-mint flavor you taste in those dark brown confections.

The fresh leaves are bitter and quite unpleasant. Dried, however, they take on a delicious, smooth flavor. And combining it with sugar helps to balance out the bitter flavors.

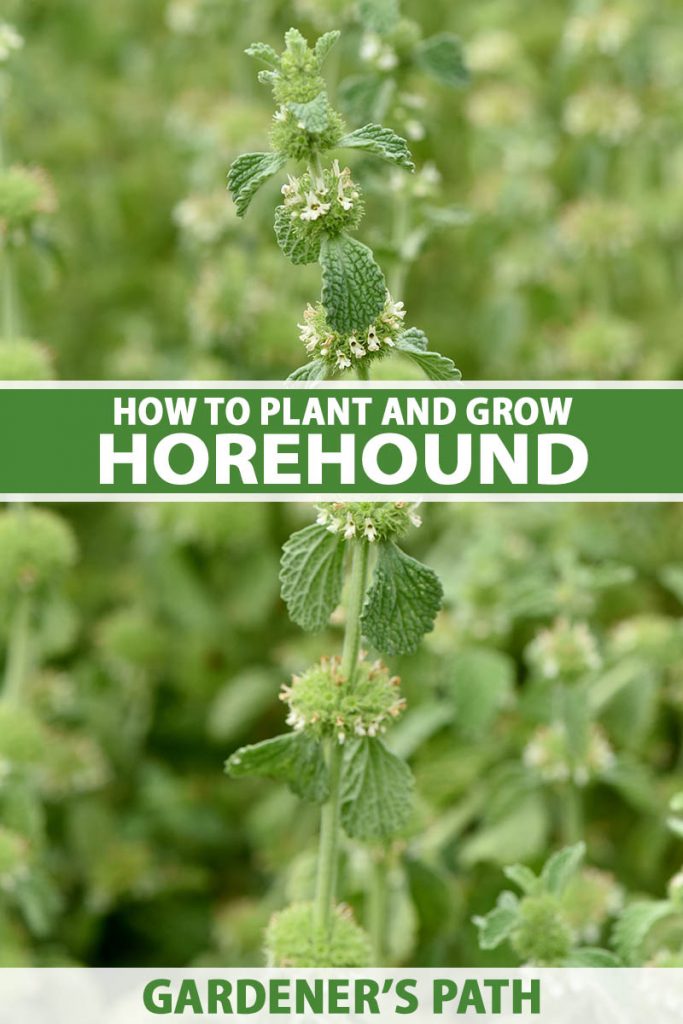

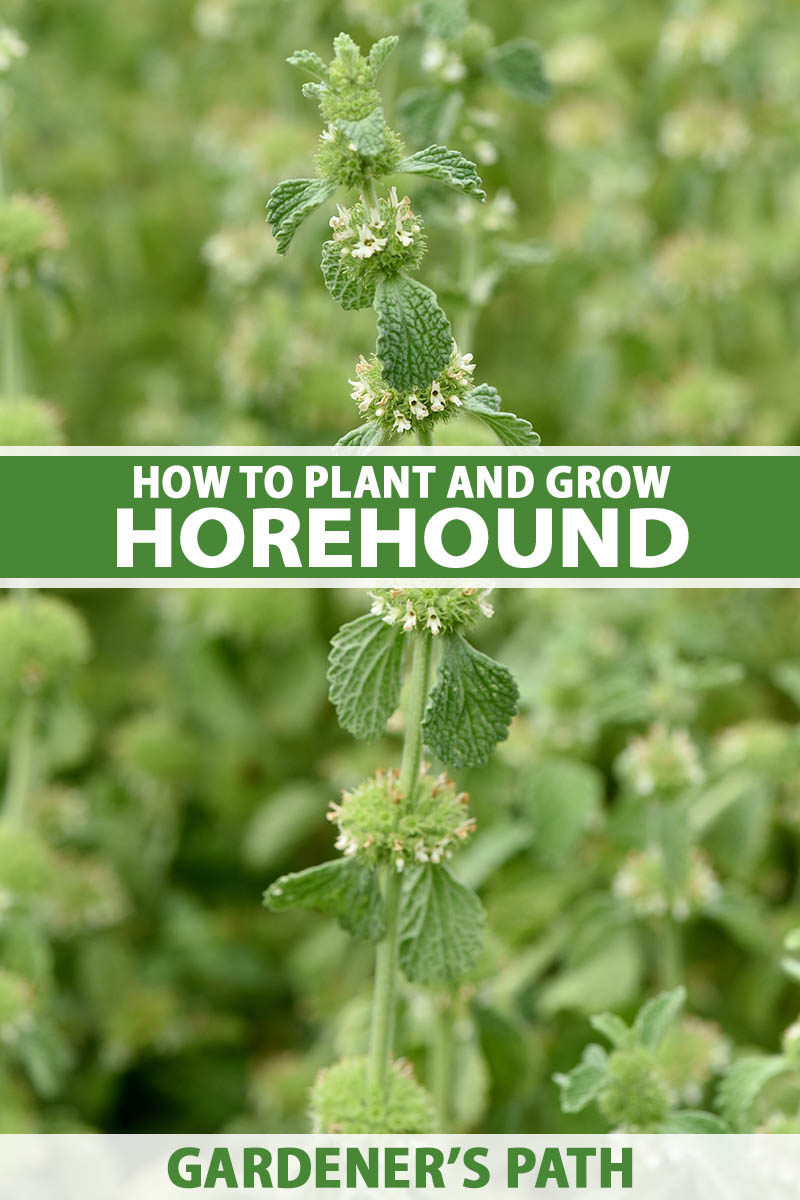

The gray-green leaves are round or oval, with a slight heart shape.

Both the leaves and stems are covered in fine hair, wherein the plant received its name.

Plants grow to about 30 inches tall and two to three feet wide. They spread via runners and self-seeding.

Horehound flowers continually throughout the summer with pink, lavender, or white tubular blossoms that are highly attractive to bees. These blossoms are also edible. Note that you might not see flowers in the first year or two of growth.

The active ingredients are several types of terpenoid compounds including marrubiin, which studies indicate could have antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic, and analgesic properties.

A Note of Caution:

When it comes to horehound, you can have too much of a good thing. If you consume an excessive amount, you’ll potentially have diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting.

It may impact blood sugar, blood pressure, and heart rhythm. While rare, the impact can be serious.

Outside of the kitchen and medicine cabinet, this plant has some excellent uses in the garden.

Many pests – like aphids and grasshoppers – are deterred by the smell of the leaves and flowers, so plant it in the garden if you need to keep pests away from susceptible plants. I plant lots of it on the exterior of my rose garden and it has made a noticeable difference.

Another word of warning, though. Like many plants in the mint family, this herb can spread rapidly and become invasive.

You might want to plant it in containers to prevent this, either submerged in the soil or above ground.

Propagation

M. vulgare prefers dry, sandy soil, but it’s not picky. It will grow in loamy and clay soils, as well.

Soil with low nutrients won’t phase it, which is why it is often found growing along roadsides and in disturbed areas. It isn’t picky about pH, either. Anything from 4.5 to 8.3 will do.

It needs well-draining soil, however. If you have poor drainage in the area where you plan to grow your plants, you should work in lots of well-aged compost.

Alternately, consider growing in raised beds or containers.

From Seed

Seeds can be started indoors or sown directly into the garden. It’s easier to start them outdoors because you can let Mother Nature do the work of cold stratifying the seeds.

Just put seeds a fourth of an inch deep in the ground in fall and you should see plants pop up the next spring.

To start them indoors, or if you’re planting in Zone 9, you’ll need to do the cold stratification work yourself.

To do this, put a cup of sand in a resealable bag or glass jar. Add seeds to the sand and mix them in. Pour water on the sand until it is completely moist – but not soggy – all the way through. Seal the bag or container and place it in the coldest part of the fridge.

Check once a week or so to see if the sand is drying out. If so, add a little more water.

After a month, the seeds are ready to leave the fridge and go into the soil. The seeds are black and stand out in the sand, so you can scoop them out with a teaspoon and plant them individually at a quarter inch deep.

What I choose to do, however, is to put a two-inch layer of a seed starting medium into a seedling tray, then I spread the sand evenly over the top of the medium. Finally, sprinkle a thin layer of fresh sand on top and give everything a spritz of water from a spray bottle.

After two or three weeks, seedlings should emerge. At that point, put the seedlings where they’ll receive indirect light for five or six hours a day and thin them so that the plants are four inches apart.

After the seedlings are about two inches tall, you can transplant them into the garden spaced about 12 inches apart.

Stem Cuttings

It’s easy to start from stem cuttings. For rooting, you’ll need to fill a small container (around 4 inches) with a general purpose potting soil.

In the summer before flowering, snip off a stem that has at least four sets of leaves. Cut just below a leaf node and strip the bottom half of leaves, taking care to leave at least two sets in place at the top.

Dip the cut end in a rooting hormone product and then place in your prepared container. Keep the cutting moist as it develops new roots, which takes about three weeks.

Once you see new growth forming, you can water as normal. That means allowing the top of the soil to dry out before adding new water.

Root Divisions

If you’ve ever divided mint, then you already know how easy dividing horehound can be!

You can divide your plant any time the soil is workable, but spring or fall is best. To get started, dig up a chunk of horehound using a garden spade.

Try to dig up at least eight inches or so in diameter and dig down about nine to 12 inches to ensure you have plenty of roots. It’s more important that you get a good bit of the roots rather than a lot of stems.

Then, use a sharp pair of gardening scissors or a gardening knife to cut through the roots and separate the plant in half.

Replace the original plant in the ground and fill in around it with soil. Plant the other half in its new spot as you would a transplant.

Layering

This is my favorite method of propagation. It’s quick, easy, and reliable, since a stem will typically send out roots wherever it comes in contact with the earth. Try layering any time in the spring, summer, or early fall.

Grab a six to eight-inch stem towards the outside of a clump and strip all the leaves from it. Lay the stem on the ground and bury it with an inch or so of soil. If needed, place a rock at the end to hold the whole thing down.

After two or three weeks, you’ll start to see new leaves emerging from the buried section of stem. You’ll likely find several new shoots emerging in several different spots along the buried stem.

Once you see two sets of leaves on at least one of the new shoots, cut the new plant away from the parent plant using a pair of clippers.

Then, dig a hole that extends out three inches around the perimeter of the new plant’s stem (or six inches in diameter around the new plant) and at least six inches deep. Lift it out of the soil and plant it in a new spot as you would a transplant.

From Seedlings/Transplanting

To plant a purchased seedling or transplant, dig a hole slightly larger and deeper than the existing container.

Gently loosen the plant from the pot and place it in the hole. Fill in around it with soil and water deeply to settle the earth.

How to Grow

This plant needs full sun. Some mints will keep pushing along even in shade, but horehound will die. It can tolerate partial shade, but you’ll likely have a smaller yield and a leggier plant.

While it is tolerant of drought, M. vulgare can’t handle standing water or a soggy environment for too long.

Don’t plant it in a spot that stays wet during the winter, and avoid planting with herbs that need a lot of water like basil, parsley, and cilantro.

Let the top few inches of soil dry out completely between watering.

It’s not yet clear why, from a scientific standpoint, but tomatoes and horehound get along well. Tomatoes tend to have a larger yield when grown next to horehound, so feel free to put them together.

Growing Tips

- Give plants full sun for best performance.

- Fertilize once per year with a balanced product.

- Let the top few inches of soil dry out completely between waterings.

Maintenance

Fertilize once in the spring with a balanced fertilizer.

Down to Earth’s Vegetable Garden fertilizer is a good option, and you can pick some up at Arbico Organics in five-pound boxes. Bonus: the cardboard can be composted once you’re done!

Down to Earth Vegetable Garden

While you don’t need to prune horehound, you might want to head out once a year and pull up clumps of it to keep the plant in check.

Just dig up the plant wherever you don’t want it, and be sure to dig deep to get all the roots.

You can always compost the excess that you’ve culled, or give the divisions away to a friend.

I also like to go out at the end of spring and give my plants a haircut. I trim them all down by about a third to encourage bushier growth.

It’s not necessary, but I think it looks nicer and I see a larger yield of leaves as a result.

Where to Buy and Horehound Relatives to Select

There aren’t any named horehound cultivars out there, so if you want to pick up a plant or seeds, you’ll see them all sold under the names common or white horehound, or just horehound.

Horehound Seeds

True Leaf Market carries 500-gram, quarter-ounce, one-ounce, and four-ounce packets of seeds if you’re interested in picking some up. And why wouldn’t you be?

A few close relatives might make nice additions to the garden as well. These all have similar growing requirements and uses, and they look quite similar.

Silver Edged Horehound

Silver edged horehound (M. rotundifolium) is a relative of the common variety that is a good option if you need something that can handle extraordinarily dry situations.

This one is more of an ornamental option, though you can eat it. It has fuzzy green leaves with a silver underside. The leaves curl up so that the underside is visible, making it look like they’re edged in silver.

This species is a low-growing type that is ideal in xeriscape gardens and makes an excellent filler in dry areas.

Like common horehound, it will spread readily, which could be a positive if you’re looking for something that will replace a water-intensive lawn. It needs no additional water once established, even in the desert.

Silver horehound differs from the common type in that it has woolier leaves and yellow flowers.

Black Horehound

Black horehound (Balotta nigra) is another close relative of white horehound from the same family, Lamiaceae.

In addition to horehound’s other uses, the black variety has been used medicinally as a sedative and as a treatment for intestinal parasites.

It has purple-lavender flowers and grows a bit taller than common horehound. It, too, can become invasive.

Managing Pests and Disease

Horehound is one of those plants that you just don’t have to worry about much, so long as you plant it in the right conditions.

Deer and rabbits don’t eat it, and it helps keep pests away rather than being bothered by them.

It can be used as a companion plant to deter grasshoppers and aphids, as we mentioned above.

It will also attract beneficial insects like bees, braconid and ichneumon wasps, and tachinid and syrphid flies.

Though it isn’t common, you may come across powdery mildew, particularly if your plants are growing in a partially shaded area or an area that stays quite humid.

Powdery mildew is caused by a variety of different fungi in the Erysiphales order.

If you see white, powdery spots on the leaves and stems of your horehound, you can be pretty sure the plant has this disease.

For some great information on treating this super-common garden foe, head on over to our guide on powdery mildew.

Even though I battle powdery mildew every year on a huge range of plants in my garden, I’ve only seen it once or twice on my horehound plants.

Harvesting

Snip the leaves and stems as needed throughout the growing season. If you want to dry the leaves and flowers, cut the stems at ground level using a pair of clippers right as the blossoms open, usually starting around 75 days after planting.

If you cut the plant back to the ground after flowering, it will usually grow a second crop. Once the plant finishes flowering for the season, the stems turn woody and the leaves lose their flavor. Unless you want to harvest seeds, there’s no point in letting the plant go to seed.

Store leaves and stems wrapped in paper towels and placed inside a zip-top bag in the refrigerator. They can last a week or two this way.

Wash the leaves right before you use them.

If you’re a fan of wildflower style bouquets, I think the horehound flower stems are beautiful in their own way, though the blossoms aren’t large and showy like some cut flowers, and they smell delicious as you walk by.

Preserving

Drying is the best way to preserve the leaves, and the plant retains its scent and flavor upon drying. Actually, the flavor improves quite a bit as the leaves dry.

To dry, hang bundles of the leaves tied together upside down in a shaded area with good air circulation.

Once they are dry and crisp to the touch, crumble the leaves and blossoms, or leave them whole and store them in an airtight container in a dark, cool spot. Stored this way, they should last for about a year or so.

You could also freeze the leaves by washing them thoroughly and placing them in a zip-top freezer bag. Squeeze out all the air and seal it. They can last about six months this way.

Recipes and Use

If you can find horehound candy or drops for sale, you may note that these don’t actually contain real horehound.

To make your own at home instead – with the real, homegrown herb – try the following:

Gather a cup of leaves (dried or fresh, it doesn’t matter) and steep them for 15 minutes in a cup of simmering water.

Add 1 3/4 to two cups sugar and bring to a boil (adjust based on your taste preference – more sugar means a less intense flavor). Boil until the mixture reaches 300°F (on my stove, this takes about 20 minutes).

Pour the mixture into a nine-inch-square baking pan lined with parchment paper and let it sit for a few minutes until it has become firm but not solid. At that point, cut the candy into small pieces.

Allow it to harden the rest of the way on the counter at room temperature, then break apart the pieces that you cut earlier.

They will stick back together slightly while the candy dries, but they should break apart easily. Store in a sealed jar.

I like to add these little candy chunks to my tea instead of honey or sugar when I have a cough or upset stomach.

The dried leaves make an interesting addition as a spice on top of meat, fish, or veggies, though I admit it’s a bit of an acquired taste.

Without the added sweetness, the leaves have a sort of smoky, bitter flavor with hints of licorice and mint.

Just remember, don’t use too much, both because the flavor can be overwhelming, and because of the aforementioned potential health concerns.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Perennial herb | Maintenance: | Low |

| Native to: | Central and Western Asia, Europe, North Africa | Tolerance: | Deer, drought |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 3-9 | Soil Type: | Sandy, loamy |

| Season: | Spring, summer | Soil pH: | 4.5-8.3 |

| Exposure: | Full sun to partial shade | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | 12 inches | Attracts: | Bees, braconid wasps, ichneumon wasps, syrphid flies, tachinid flies |

| Planting Depth: | 1/4 inch (seeds) | Companion Planting: | Bee balm, echinacea, lemon balm, tomatoes, peppers |

| Height: | Up to 30 inches | Avoid Planting With: | Basil, cilantro, parsley |

| Spread: | 2-3 feet | Family: | Lamiaceae |

| Growth Rate: | Fast | ||

| Water Needs: | Low | Genus: | Marrubium |

| Common Pests and Disease: | Mealybugs, spider mites; powdery mildew, root rot | Species: | Vulgare |

Time to Give Horehound Its Due

Whether you intend to make beer, candy, or medicine with it, or none of the above, horehound deserves a spot in the garden simply because it makes such a good companion plant.

Anything that requires little maintenance, but will help you in the never-ending battle against grasshoppers and aphids, is an herb garden essential in my book.

What about you? How do you plan to use your homegrown horehound? Let us know in the comments!

Feel like this guide helped you become a horehound expert? We have some other great guides for growing herbs in the mint (Lamiaceae) family to read next:

About Kristine Lofgren

Kristine Lofgren is a writer, photographer, reader, and gardening lover from outside Portland, Oregon. She was raised in the Utah desert, and made her way to the rainforests of the Pacific Northwest with her husband and two dogs in 2018. Her passion is focused these days on growing ornamental edibles, and foraging for food in the urban and suburban landscape.

[ad_2]

Source link