Veronica Simpson talks to architect Lina Ghotmeh about the building she designed in Beirut, and which thankfully survived the explosion in 2020

Words by Veronica Simpson

There is a strange but intriguing practice I’ve heard architects mention, where they ask themselves, in the early design stages, to imagine what their proposed building might look like as a ruin; the idea, I’ve been told, is to ensure you leave a good-looking ruin. But, perhaps best of all, is to design a building that can survive a disaster intact. Such an outcome was not one the Lebanese-born, Paris-based architect Lina Ghotmeh was actively looking for when she imagined Stone Garden, a craggy, plant-filled apartment block, its sculpted concrete contours rising 13-storeys high between Beirut’s city centre and the docks. But in summer 2020, when a dockyard fire engulfed a nearby warehouse containing ammonium nitrate (which should have been disposed of years before), that building exploded, tragically causing over 200 deaths and leaving a crater 140m wide. Amazingly, Ghotmeh’s building remained intact apart from a few broken windows, despite being only a mile from the centre of the blast.

It had taken ten years to complete this, her first building in her home town of Beirut. In early 2020, just as the building was welcoming its first tenants, and before the horrific explosion, Ghotmeh told Domus magazine she envisaged it as inhabited sculpture, a tribute to the decades of strife her city had seen during the 15-year civil war – the combed concrete facade reminiscent of the bullet scars you can still see peppering the city’s older structures – and hopes of a better future. It was, she said, ‘an invitation not to repeat history but to cherish life and cohesion’. Those words, post blast, have gained an extra poignancy, given how carelessly so much of the city’s centre and precious coastline has been exploited by profit-seeking speculative development since the 1990s, aided and abetted by the laissez-faire attitude of local government (at least some of whom were forced to resign after the blast).

But it seems even more poetic that this building still stands given the friendship and spirit of care in which it was conceived and gestated. The idea was born over a decade ago when Ghotmeh met photographer Fouad Elkoury, who shared with her his dreams for a photographic archive and art foundation dedicated to recording the city in all its evolutions. He had a potential site for it, on a plot of land left to his family by his renowned modernist architect father Pierre el-Khoury, after he died. The idea grew to create such a cultural gathering place in the ground floor of an apartment block, some of whose apartments would be lived in by Elkoury and his family, and the rest sold to finance the construction.

Inside the Beirut apartment, looking out towards the dockside. Image Credit: IWAN BAAN

Ghotmeh agrees that this client, this city, and the situation were optimal in that they allowed her to evolve the unusual and porous form of Stone Garden – inspired by some of the rugged rock structures along the Lebanese coast – and stipulate integral planters at each level as a way of prioritising nature. Stone Garden is a statement against the casual destruction of the city’s surrounding landscape, she says. But her approach remains consistent with a methodology she first developed while an undergraduate architecture student at the American University of Beirut, and then developed while studying – and then teaching – at the École Spéciale d’Architecture in Paris. She calls it ‘the archaeology of the future’.

She elaborated on this when we spoke, by Zoom, in spring 2021. ‘I like to think about archaeology because it opens one’s imagination, to think how people once lived there. Every place is unfinished. I like to tap into this sense of the unfinished. When we are working on this project, or other projects, in the office, we are always trying to decide the history of the place, but also to… push the reading of the site – its typical characteristics, its lines, the boundary. What does it mean? How does it relate to the context?’

Care and craftsmanship, the way Ghotmeh tells it, is not just essential in the design, detailing and construction of a building, it is also important in all other aspects of a project’s evolution. ‘For a long time the process was stopping and starting, the making of the building and the financial set up, finding the right developer,’ she says. ‘The client [Elkoury] – he is an artist, a photographer – he respected my profession. He wanted to develop a project that is meaningful. That was really precious. And then also the developer that came to build the project was amazing. He’s someone who trusted the vision for the project and went along with our experiment with the envelope as part of a very enriching dialogue.

Ghotmeh currently has projects on the go in Tours and Normandy

‘With such people it’s possible to achieve your architectural ambitions. I had to put a lot of myself into the project, but I think it’s worth it because I have an emotional attachment to it too.’

But when it comes to the dockside disaster, one shouldn’t romanticise too much: there are fundamental, structural reasons why the building withstood that blast. The whole of the building is concrete, built in situ. So, says Ghotmeh, ‘as architecture, it was really all structure’. Buildings further away covered with cladding were ripped apart. ‘Here, there weren’t any add-ons… It was the integrity of the envelope.’ Having so many apertures, deep balconies and such an unorthodox shape must have helped too.

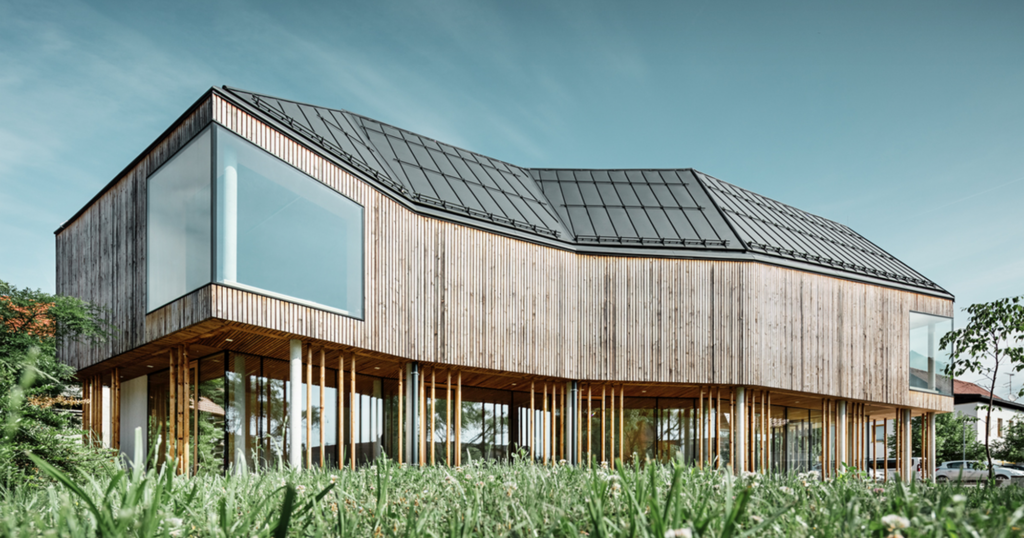

Now, after the ups and downs of 2020, Lina Ghotmeh Architecture’s projects are in full flow, including the National Choreographic Centre in Tours and a new workshop space for luxury goods brand Hermès in the Normandy countryside, finishing next year. And here, her archaeological instincts have been rewarded again with the discovery, during excavations, of an ancient saddlery having previously existed on that site (Hermès was founded in 1837 as a high-end harness workshop). As she says herself, ‘Sometimes I wonder whether I am constructing something new or revealing what was already there.’