[ad_1]

The call to nature is in us all. That yearning to be out of doors, reconnecting with our wilder selves, grows ever stronger the more we modernize and urbanize.

It’s a paradox, then, that architects – makers of the built environment – should preoccupy themselves with retreats in nature. And yet they do, with a cultish obsession. In Australia, bush sites, rural fields and coastal dunes are all favourite places for architects to test their ideas about utility of purpose and poetics of form on a somewhat miniature scale.

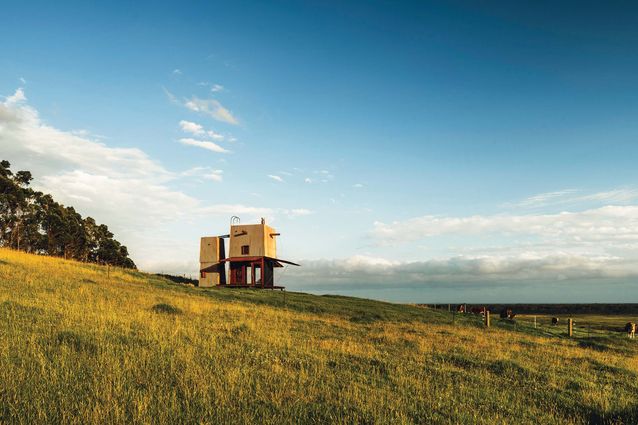

Located in Berry on New South Wales’s south coast, Permanent Camping II (2020) by Sydney architect Rob Brown of Casey Brown Architecture looks out to the ocean from a hillside on Dharawal Country. It’s a long-awaited sequel to his Permanent Camping (PC I), a tiny, corrugated, copper-clad Dalek sited stoically on a sheep station in Mudgee in the state’s central west.

Winch-operated panels open the structure to the landscape and provide shade.

Image:

Andrew Loiterton

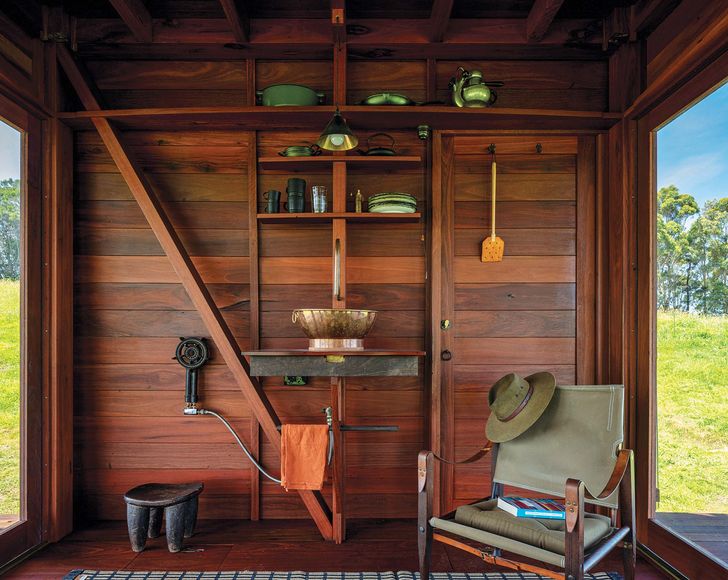

Scaled to match a standing human, PC I’s monastic frugality of space is held in exquisite tension with a finely crafted interior of recycled ironbark that includes a sleeping loft and a small kitchen with a slow-combustion wood stove.

When completed in 2007, PC I sparked a local renaissance in rustic architecture and was widely published internationally, including in one of my favourite books: Cabin Porn (2015).

Both versions are conceived as a 1–2 person retreat. The original, a two-storey tower, wrapped in copper and with side walls that swing open from the ground to create wide, covered verandahs to the north, east and west, has a tiny three-by-three-metre footprint.

Located to the south are a water tank and winches that operate the verandah roof. When not in use, the flaps are closed, protecting the timber-and-glass interior from the elements and bushfire. “Like a flower that opens during the day to enjoy the sun and closes at night to protect its delicate interior,” Rob explains.

“The original idea for PC I was to be a step up from camping, offering a comfortable bed, a fireplace and a place to eat and enjoy nature, all in a small footprint structure that still protects you from the elements. The second edition learns from the original, like a new series car: it takes the concept, then updates and upscales it,” Rob says.

The interior of recycled ironbark is a warm and delicate antidote to the copper exterior.

Image:

Andrew Loiterton

Materials are similar – copper and ironbark – and the same prefabrication method is used, but there are new amenities: a separate composting WC with enclosed water tank, a gravity-fed outdoor shower, solar roof panels for an off-grid experience, and a lightning conductor (just in case).

Rob specializes in designing homes along the Pacific edge and in rural regions. These homes are all much larger than the PCs, but they arguably deliver the same promise: a place in nature within a building that’s curiously at odds with and yet comfortable in the landscape.

A different material approach has been taken by Richard Stampton Architects in Bush Camp 1 (2016), a more machined-looking set of steel structures on a private site in the coastal town of Yanakie, on the edge of Wilson’s Promontory in Victoria.

The shelters are pared back to simple geometric forms that emphasize their impermanence.

Image:

Rory Gardiner

For traditional custodians of the land, including the Gunaikurnai and Boon Wurrung peoples, this area was a sacred meeting place. For the family who commissioned Bush Camp 1, the site is a restorative place.

Richard’s camping structures elegantly solve the perennial problem of a lumpy, soggy floor, with an elevated sleeping platform of plywood on web-forged steel, slung across a hollow, galvanized steel A-frame. Side flaps of insulated polypropylene move up and down for shelter.

His design influences include tents, obviously – Richard is an experienced camper – as well as Peter McIntyre’s Butterfly House (1955) in Kew, Victoria, and Italian architects Archizoom’s unbuilt No-Stop City (1969).

The finesse and strength of Bush Camp I reflects a mastery of materials and geometry that prevents Richard’s work from being pigeon-holed. Before establishing his practice in Phillip Island, Richard worked with Renzo Piano Building Workshop in Paris. A current project in Yanakie is a “house” where circles of rammed earth, like local rainwater tanks, are abstracted into the landscape and incised with windows and doors. “The clients’ brief is for a house that makes you connect with the land through occupying it,” says Richard.

In the lush Byron Bay hinterland of northern New South Wales, traditionally Bundjalung Country, Broken Camp (2020) by Atelier Luke is a picnic and camping platform for a family living on a private rural property. The site sits among rolling hills, ridge lines and littoral rainforest, so the pavilion is designed to both frame the views and be an object in the landscape.

Broken Camp is an open-sided camping shelter that also frames views of the landscape.

Image:

Michael Nicholson

Like Permanent Camping, its materials reference the local vernacular of steel and hardwood, but Broken Camp differs in that it’s a permanently open structure.

Its sheltering frame is native spotted gum with a thin cladding of weathering steel, like canvas stretched over tent poles. Its broad timber deck terminates at either end in gathering points around fire: a wood-fired oven at one end, a fire pit at the other.

Atelier Luke is architect Luke Hayward and interior designer Junko Nakatsuka. The couple works between Australia and Japan, and some aspects of Broken Camp are informed by one of Atelier Luke’s domestic renovation projects in Kyoto – particularly the use of levels and the treatment of architecture as supersized furniture. Other influences, Luke says, include “the formal simplicity and structural thinness of tents, and the importance of resilience.”

Far further north, in Queensland’s tropical Daintree, Melbourne architect Tim Sullivan (Sullivan and Charles) created a tiny fold-down lock-up shack on a small block on Wonga Beach – Kuku Yalanji Country.

In school holidays, his family treks some 3,000 kilometres north of their East Melbourne home to the Wonga Shack, where they spend time fishing, swimming, dreaming and briefly living like nomads.

On a four-by-four-metre footprint, Tim has squeezed a bedroom, kitchen, bathroom, toilet and laundry into a cubic arrangement. Materials are basic: fibre-cement sheeting, corrugated iron and, for the kitchen, formply. The cube was made and pre-assembled in a Footscray factory, freighted by train to Cairns and then trucked to the site.

“It’s a tiny building, but the space it radiates is huge, because living, dining and cooking essentially happen outdoors. It’s pretty exciting to arrive, open up the box and set up our temporary home,” Tim says.

As well as tapping into our escapist desires with the promise of seclusion and retreat, each of these small, highly considered structures asks us a much bigger question: “How much do we really need to live?”

[ad_2]

Source link