[ad_1]

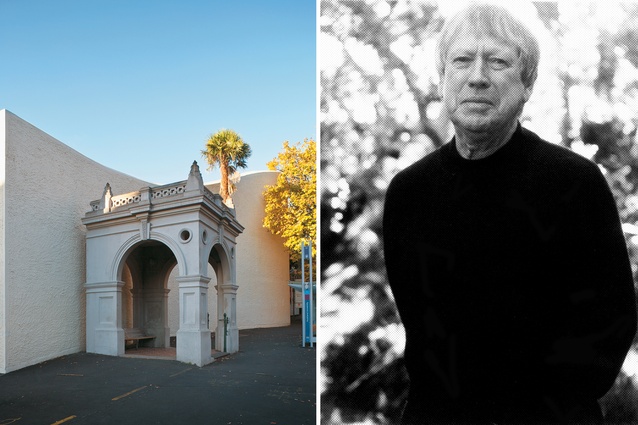

NZIA Gold Medal Citation

Jack Manning has demonstrated his architectural ability in consistent manner, but never in repetitive form, in a career stretching over half a century. Throughout that career, which received an early stimulus in the office of Group Architects, Jack’s competence has been matched by his design confidence. He has not been deterred by the challenges of scale or divergent typologies: his notable work ranges from his own family house, built when he was a young architect, to the Majestic Centre, the Wellington office tower he designed 30 years later.

In a profession that accommodates various proficiencies, Jack has always been, in essence, a designer. As he came from a modest background, did not possess a ready-made network of prospective clients and, by his own admission, is not naturally inclined to commercial activity, his advancement has been based on the realisation of his design talent. More than that, Jack has a thorough-going appreciation of how buildings are put together. In this respect, he epitomises the virtues and values of his generation of architects, a generation for whom the art of drawing was inseparable from the craft of making.

Jack’s reserve and disinterest in self-promotion should not disguise his determination. He has always aimed high, and followed his own trajectory; his response, when opportunities presented themselves, was never ‘why’, but always ‘why not’. If Mies van der Rohe could do a curtain wall building in New York City, then why couldn’t he himself do one in Auckland? Fifty years on, the AMP Building Jack designed when he was with Thorpe Cutter Pickmere & Douglas is still a graceful presence on the corner of Queen and Victoria Streets.

Innovation and adaptability have been constant features of Jack’s architecture. In New Zealand, ambition frequently outstrips budgets, but from the start of his career, Jack has refused to let financial constraints handicap architectural expression or experiment. The more-from-less buildings he designed at the Auckland Teachers Training College campus transcended the limitations of local circumstances and probably confounded contemporary expectations. Twenty years later, in practice with David Mitchell, he married boldness and delight at the University of Auckland Music School, a rare local occurrence of successful post-modernism.

Now in his eighties, Jack continues to practice, most latterly on a series of houses as singular as ever, and his evident enjoyment of design is a sure sign that he chose the right vocation. Assured of his own ability, he has been a mentor to many of the architects with whom he has worked. Widely read, well informed, possessing firm opinions but alive to new ideas, Jack is a fine representative of the profession to which he has dedicated himself, and a most worthy recipient of the New Zealand Institute of Architects’ Gold Medal.

John Walsh (JW): Let’s start at the beginning, Jack. You’re an Aucklander?

Jack Manning (JM): I am, a North Shore boy. I grew up in Devonport and Takapuna, mainly. My family life was very suburban. It’s strange but there was no interest in any of the arts. My mother was a pianist and she played organ in the church choir but apart from that there was no interest in literature, painting or anything like that. So there weren’t a lot of things that moved me into something like architecture, and it was bit of a toss-up as to what I did when I finished secondary school.

Where did you go to high school?

JM: I went to St Peter’s College in Newmarket. I had the idea that I might do either journalism or engineering. Then, during the last school holidays before going to university – I’d always been reasonably good at sketching – I thought maybe I should try architecture. There was an architect who lived reasonably close by in Takapuna and he looked as though he was doing okay. So, that’s what I did. I went and enrolled in architecture. I was in a minority of people straight from school because most of the class were rehab students who had been in the Armed Forces. This was in 1946.

I had no idea what architecture was about. The first year was mainly learning to do manual drawings, with T-squares and so forth. It wasn’t too much of a problem. The second year I was really floundering and Dick Toy wasn’t terribly impressed with me, I could see that. Anyhow, I had to re-do second year and towards the end of the second year I could see that Toy was thinking I wasn’t a complete write off. In the third year, with Vernon Brown, I started to feel I knew what I was doing.

I didn’t have a very strong relationship with Toy but I could connect with Vernon Brown pretty well. I’ve got a small section of a Japanese temple that he gave me. He must have just about dismantled the whole temple to have had all the chunks to hand out to people. In that year I won the Memorial Prize – it was the third year art prize.

In the fourth year we had Peter Middleton and Boland from England who had just arrived. The first project that we had to do, everybody was failed, and there was virtually a riot. The School at that time was going through a bit of ferment. Bill Wilson and some others, who were a few years ahead, had been arguing a lot with the staff about what modern architecture was. At the time the School was very dull and it didn’t seem to recognise what was happening overseas. Dick Hobin was one of the ringleaders of our mini revolt. We ended up talking to the dean, Maidment I think it was…

My work at the time was pretty wild. I was undisciplined, and my work was incredibly immature. I had to repeat a term to get through fourth year, which I did. After leaving the School I went to the Auckland Education Board. I was there for a couple of years. I felt that I needed to find out a little bit about real building.

JW: Did you get to do real building with the Education Board?

JM: Well, you got to do real detail. It was more or less stock timber joinery and stock working drawings. There was absolutely nothing to be gained in terms of design experience, but it did enable me to get my feet on my ground as regards to the practicalities of building. Then around 1953 or ’54 I went to work for The Group for about 18 months as a draftsman.

It was great. I didn’t get to design a thing. Bill Wilson and Ivan Juriss and Jim Hackshaw all did their own work, and did their own working drawings as well. So I didn’t work on any of the masterpieces of the period, but the office was absolutely vibrant. Bill Wilson, in particular, was a complete international man in a way. He was into literature, music and drama – everything. You’d be discussing Le Corbusier, Aalto, Japanese traditional architecture, socialism. Everything was up for discussion. It was quite electric working there.

JW: Bill Wilson must have been quite a charismatic figure.

JM: He was incredibly charismatic. He was a chain smoker. I can get an image of him standing surrounded in smoke as he talked. He would often be well behind in getting his jobs out, and then he’d work until three o’clock in the morning and come in the next day with his eyes almost closed. He was quite an amazing guy. It’s just such a pity that he died so young – I think

he was about 46 – because New Zealand architecture could have happily done with another 20 years of his presence.

JW: Why did you leave The Group?

JM: Well, they ran out of work. So I went to Thorpe, Cutter, Pickmere and Douglas. I worked for a while on the Manukau drainage plant buildings and then along came the AMP building on Victoria Street, which I did. Mick Cutter was the partner in charge but most of the time he was teaching up at the university so he didn’t draw anything. Lever House and the Seagram Building had been built recently and were reasonable sorts of model for what we did at AMP, which wasn’t a free standing tower, it was just a complete site. You only had two frontages for a tower. It was probably one of the first curtain wall buildings in the city, and with the strong vertical ribs and the extent of glass, I think it’s still quite a vital-looking building.

JW: Was it difficult to get the client to agree to what was a very modern building?

JM: I wasn’t involved in the actual selling of it to the AMP officials, but we got a model made. It was a dreadful model, actually. It was made with little strips of steel glued to celluloid sides but it just looked really clunky. I’m surprised that AMP bought it but they did.

JW: Do you like the Seagram Building?

JM: Yes I do. What it has done, though, is spawned a massive number of similar buildings, and the thing about it is that if you’re going to be a minimalist it’s got to be pretty pure and pretty perfect. Mies was able to do that, but the buildings that every American city now has – they’ve all got two or three big Miesian buildings – they’re all just a bit boring, I’m afraid.

JW: What happened after Thorpe Cutter Pickmere and Douglas?

JM: I left them to go to Auckland City Council because that seemed to be, at the time, one of the best places to work in Auckland. Tim Donald was the chief architect. Ewan Wainscott was deputy and there were a dozen architects on the staff as well – John Goldwater was there. It had a good reputation as a place to work so I went there. I was doing flats in Freemans Bay for a while and then ended up working on the new city library which was proposed for the site it now occupies. Ewan Wainscott was in charge of the design and I was quite determined that we weren’t going to end up with a supermarket-type library which was all the rage in America at the time. I was aiming for something a bit more on the European model that Aalto had been doing.

I did the sketch drawings for the things. This was the end of ’63, and then the project was mothballed because there was a problem about the site.

So, anyhow, I went back to Thorpe Cutter Pickmere and Douglas to do a redevelopment of Ardmore Teachers’ College which never went ahead. While I was there the decision was made to turn Auckland Teachers’ College, which was a primary teaching college, into both a secondary and primary teaching college one on the same site. So there was a new primary building, a new secondary building, a teaching building, a gymnasium for each, a library to be shared between the two and common rooms for the students. I was the architect in charge of the project. David Mitchell had come to work at the firm and he was another senior architect on it, and there were a whole lot of graduates straight out of architecture school, people like Peter Sargisson, Neil Simmons and Peter Hill.

It was a really lively team and the buildings that resulted from it were quite striking. They were fairly simply built. There was a fair amount of raw concrete and we used a lot of cement panels as cladding, pre-coated with polyurethane. This was often in dazzling whites and primary colours. There were some quite startling things about the buildings that were really quite vibrant and vital.

JW: Were you involved in the master planning of that site?

JM: Yes, it’s a wonderful site. That was a very enjoyable experience, working with all those younger guys from the university. I left Thorpe, Cutter, Pickmere and Douglas and went to join Peter Hill in Parnell. He had started his own practice there and was doing work for Les Harvey in redeveloping Parnell, was doing quite a few Kentucky Fried Chicken outlets at the same time. I went there because Thorpe Cutter had realised I wasn’t the businessman that they were really looking for. My promotion prospects weren’t terribly good so that was why I decided to leave. I didn’t have a lot of work at the start but I got some Education Department work at Epsom Girls’ Grammar School and later Orewa College.

JW: So you were a designer not a businessman?

JM: I’ve never been a businessman. I’ve never been much of a technocrat, either. I take detailing pretty seriously. I spend a lot of time trying to work things out that other people might know off-hand, but I’m very much the designer type rather than the businessman type.

JW: What year are we in now, Jack?

JM: About 1975 or so. Shortly after I started with Peter Hill, David Mitchell came and joined us. He was doing his famous first house for the Gibbs and so forth. I was doing a music suite, drama suite and senior girls’ common room at Epsom Girls’ Grammar on quite a large site fronting onto Gillies Avenue. These were very domestic buildings, connected by a covered way. History later caught up with Epsom Girls’ Grammar and the school’s roll jumped alarmingly and the site just couldn’t tolerate low density development. The buildings I had designed ended up being replaced by multi-storey classroom blocks.

Then we got the Music School building at the University of Auckland. This was a joint effort by David Mitchell and myself. It wasn’t the easiest of problems because the school had existing premises in Princes Street in a beautiful old building that sort of rambled all over the place. There were music rooms scattered around, and the music would be clashing all the time. They just put up with it – there’d be pianos and cellos all doing different things. But the School liked the openness of the building and the last thing they wanted was to end up with an impersonal sort of building, with everything air-conditioned.

David and I had exactly the same attitude to the new building, but it wasn’t going to be all that easy on the site. For a start, the site was very small, but the real problem was the horrendous noise from Symonds Street. It was about 80 decibels on the boundary. We had Harold Marshall as our acoustic consultant, and without him we just wouldn’t have got anywhere. We said we just have to build a solid barrier on the street, and that’s why there’s not a window in that wall. And to make it amenable to the public it needed to be shaped in both plan and elevation. But once we had the wall we had a moderately quiet courtyard inside and the music staff were happy with the idea that there would be music interference to a reasonable extent between room to room. We were able to achieve this by extending the walls of small music rooms and studies out to give a little barrier on each side. Also, by adjusting the openings that you had from the room to the outside, you could create a more circuitous path for the sound to travel.

JW: What do you think of the Music School now?

JM: I think it’s a lovely, sensual building. There are a few touches of post-modernism in it – if there’d been a lot more we could have been embarrassed about it later. There are so few, really, that people don’t put it in the post-modern category.

JW: You were generally careful with your post-modern indulgence?

JM: I think we were lucky that a lot of the post-modernist stuff we were designing never got built. At first we thought post-modernism was good because it was fresh and just so liberating, but I think it was liberating in the wrong direction somehow. All the theatrics and the historicism of post-modernism, and the irony… I mean, architecture is an art. You’ve got to

be very careful with irony attached to art. It just demeans it.

JW: What do you think about the vogue that emerged in the late 1990s and early 2000s for a neo-modernist kind of architecture – minimalist, very slick, very clean, often very expensive, and highly reliant on beautiful materials.

JM: I’m happy with any sort of architecture as long as it’s convincing and works. As I said, you’ve got to be pretty pure and extremely sensitive to make minimalism work as well as Mies did. I think Australian, New Zealand and American domestic architecture have all got the same similarities these days. The battle for modern architecture is well and truly over. Modern architecture has won, and I think the average client these days is looking for something radical. They actually want this sort of stuff now. It’s the norm. Modern architecture is a fashion like any of the other fashions.

JW: After the Music School did you and David stay working together?

JM: Yes, by this time David and I had moved into High Street in Auckland. After the Music School we got a lot of work for developers. As far as I can remember none of it actually got built, for which we were fairly grateful. We did do a scheme for the Britomart Place area when there was a council competition down there. This was done with Rainbow Corporation – I don’t know how many millions of dollars worth of building there were.

We had models made of all these buildings and we had a number of other architects helping –Noel Lane, Richard Street, I think, Richard Priest. I don’t want to demean Rainbow Corporation’s ideas for wanting to do it, it was the Council who put it out to tender. We didn’t win it, I forget who did, but it would have been hard to look at it now if it had all been built. We would have transformed Auckland.

JW: And not necessarily in a good way?

JM: Well, yeah. I was working at that stage with Evan Davies who was with Rainbow Corporation and later with Primac Holdings when they did the Majestic Building a little bit later on, and he was a great guy to work with. The Britomart project was pretty much over-inflated. The Majestic Centre was a really good attempt by Primac to do a landmark building and they had the belief that the area where they were going to build this building was going to become the centre of the Wellington business district. It didn’t end up like that because most of the other projects never went ahead.

The Majestic did go ahead, and it was quite an incredible project to work on. Evan Davies showed a lot of faith in us, considering the biggest building we’d done before was the Teachers’ College redevelopment and the Music School. But the Majestic Centre consisted of a retail podium and a tower which was the tallest in Wellington, by a little bit.

My own feeling was that I wanted to make this a contribution to the identity of the city, a lot like some of the New York skyscrapers. I was very interested in getting a relationship between Willis Street and the building and so the podium is hard up along the Willis Street boundary and the tower, which is set back from the top of the triangle, has got the same material as the podium – sort of red granite – and it faces and fronts onto that street. The entry to the tower is further up in Boulcott Street but we also brought in an atrium that came in from Willis Street. It got you up

by means of escalators to the tower foyer. The tower itself was subject to wind control problems and had to be wind-tunnel tested to get approval from the city council.

Basically, you needed to get something like a circular tower. It’s the best shape for avoiding wind problems in the street below. The side boundaries are set back from the boundary to the tower and we’ve got precast concrete panels with a window in each panel. Around on the western side, there’s a curtain wall on a curve that fronts onto Boulcott Street and has an expansive view of the whole area. The top of the tower has got a penthouse with a light feature that is quite distinctive for the building. I’ve thought, in retrospect that I’d do it differently if I was doing it again. It has a little bit of an Art Deco feel, and I’d probably finish it off differently these days.

JW: Have houses featured much in your career?

JM: They have lately and I’ve really enjoyed doing houses. They’re small scale, things happen quickly, and you’ve got to work with clients. I’ve been lucky with clients. The clients for the houses I’ve done have all been good people, really nice people who’ve worked with the ideas that I’ve put forward and generally been in agreement and thoroughly supportive of things I’ve done.

JW: When did you go out on your own?

JM: Probably about 1990. I felt that I needed to, just to see how I’d go on my own. David and Julie Stout were working together as a team at that stage so it worked out okay. There’s also an age thing. I was getting to an age where I was starting to think I should retire. I haven’t.

JW: Why not?

JM: I don’t know. I’ve got a couple of alteration jobs which I’m doing at the moment. When they’re finished I might just decide that it’s time.

JW: Let’s talk about houses.

JM: My own house was done about the same time that I was working for Auckland City Council. I finished it in 1960, but the houses I’ve done since the Majestic Centre… I did a house at Tauranga which I was very pleased with. It was a large rural section, countryside rolling towards the coast. It was a gently sloping site and it suddenly had a steep ridge right across the middle of it.

My first idea for that house was that we would actually run obliquely over the ridge and take advantage of the dramatic possibilities but the owners wanted a more private building, so it was set back from the ridge. We ended up with an L-shaped house. We tried various things but the budget kept running into problems, so theoretically it was a fairly simple L-shape with a pitched roof sloping towards the north and the west with a valley in between. The middle of the L is basically full height, single storied so you have a high dining room/living room and so forth. It’s quite dramatic in a way because of the fact that the two floors were fairly open. I used double glazing around the top of the house under the roof to keep the warmth in, and I was quite delighted in the way the rear of the house and the two back faces of the L look like the back of a grandstand. It worked out very nicely in the end. It was easier to do than the sunny frontage on

the other side.

The next job I did was the Cathcart House at Glendowie. This was built by the owner who’s a builder. He took 10 years to do it, from the inception to the completion, and he built every bit of it – concrete, roofing, tile work and everything. It’s on a nice site overlooking Tamaki Basin, one back from the edge of the cliff. On the frontage was a low house that enabled him to overlook it. It’s a long linear house with a barrel-vaulted roof.

JW: Do you see yourself as an Auckland architect – an architect shaped and influenced by this place?

JM: To an extent. Another house that I’ve just finished is down in Christchurch and in a way I feel as though I’m colonising Christchurch because it still strikes that the house has an Auckland feel about it. You have the opportunity and the encouragement to open the place up when the weather is good. The living room has doors that slide back and the dining room has bi-folds which open out onto a decent-size deck, so the design presupposes the same sort of outdoor living that you’d expect in Auckland.

JW: When you look at your career, do you recognise constant factors or themes. Are there ideological anchors?

JM: That’s a hard question to answer. Easy question to ask. You know, I feel that an architect’s job is to basically design buildings that are appropriate to the dignity of the human condition. I know this sounds a little bit pompous. I like my buildings to be straightforward and mainstream as to how they work. I have a fairly honest approach to materials. I don’t like the idea of doing manipulative buildings that try to impress. I’m not keen on buildings that fantasise what human life is all about. I tend to try for a level of realism.

JW: Obviously hasn’t stopped you designing some quite virtuoso buildings, such as the Music School and the Majestic Centre.

JM: You often find when you’re doing a design that you come across something you weren’t expecting. An option that is quite unexpected comes up that really strikes you as interesting and new. In architecture you’ve got to keep on moving and doing things freshly otherwise you may as well give up. But when you do get something like a breakthrough you need to run with it and reinforce it as much as you can.

JW: And see where it goes?

JM: Yes. I’ve always liked to do work that’s has a little bit of an edge to it. The last thing you want to do is things that are the obvious answer to every problem. I always like to go a little bit deeper than the sort of obvious in my work.

JW: Your house was obviously a wonderful opportunity for you to design a home for your family. It has been your home now for 50 years.

JM: It’s much second nature for me to be living here. I’m never going to sell the house. It means a lot to my family as well. Of course, it may not be possible to keep it in the family when I go… I don’t think there’s much more I can say about this house. I’ve really enjoyed living here. It’s a really peaceful place to come home to every day.

JW: In the late 1950s, this was what new modern architecture looked like in Auckland. A lot of its design principles were shared by your modernist contemporaries.

JM: Yes, but I find myself using the same sort of principles in the stuff I do these days. The window seat over there, I don’t know how many window seats I’ve done… It’s a way of defining a function. The alternative is free-standing seating but it can be quite nice to relate to a window seat and the outdoors by opening the window out.

JW: Has architecture been the right career for you, Jack?

JM: I can’t imagine myself doing anything else. I remember Peter Middleton in fourth year telling me he didn’t think I had the persistence to be an architect, and he advised me to go to art school. I think that doggedness is one of the things I’ve shown over the years.

JW: And so, the Gold Medal.

JM: Yeah I’ve got to say it was a surprise – a good surprise. I didn’t think anybody else had noticed what I was doing.

JW: Obviously, they have. I know that David Mitchell has always been highly appreciative of your work, and of you.

JM: Well, it’s mutual. I think David is one of the best architects in the country, without a doubt. Always has been.

JW: Congratulations on the Gold Medal, Jack – I envy your life well lived.

[ad_2]

Source link