Aspidistra elatior

Cast-iron plant might sound like a strange name for a tropical evergreen, but once you realize how exceptionally tough this plant is, you’ll understand the label.

Aspidistra elatior is incredibly tolerant of neglect. Drought barely phases it, low light isn’t a problem, and a lack of fertilizer is no big deal.

It’s rarely troubled by pests or diseases, and when it is, it shrugs them off without much trouble.

In fact, this plant’s only weaknesses seem to be full sun and soggy soil. And even direct sun probably won’t kill it, though it will burn the leaves.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

I’m sure I sound like I’m the head of the cast-iron plant fan club here, but it’s really hard not to love a plant that keeps on truckin’ no matter what’s thrown at it.

If you can’t wait to jump in and learn more, here’s what we’ll discuss coming up:

If you’re tired of pampering your houseplants only to have them fail on you time and again, cast-iron plants are the antidote to a brown thumb. Here we go!

What Is a Cast-Iron Plant?

The cast-iron plant (Aspidistra elatior) is native to Taiwan and the southern islands of Japan, where it grows in the understory of the forest. It features long, tapered leaves that are glossy green, sometimes with stripes or spots.

It produces strange-looking purple flowers that emerge out of the rhizome at ground level, but this rarely happens indoors. If it does, lean down close to the soil and give the flower a sniff. It smells kinda musty, a lot like a mushroom.

If you’re wondering why on earth a plant would send a stinky flower out of the soil, this is because it’s trying to attract fungus gnats (Cordyla sixi and Bradysia spp.).

Yep, those annoying little pests that plague houseplants, buzzing around your head, accidentally jetting into your nose, and landing in your glass of wine, are indispensable toA. elatior.

Botanists Kenji Suetsugu at Kobe University and Masahiro Sueyoshi at the Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute in Tsukuba, Japan, hunkered down to study the pollination of these unusual flowers.

Their research was published in Ecology, the journal for the Ecological Society of America, in 2017.

They discovered that fungus gnats would enter the flower, likely thinking it was a mushroom that they could feed on, only to re-emerge in what one might imagine is abject disappointment at the lack of a fungal buffet.

The flower, on the other hand, got what it wanted. The gnats were covered in pollen, which they transferred to the next flower as they looked for another meal.

Of course, these were a different group of fungus gnats than the ones you’d probably find in your home, since the ones in the study are native to Japan, but that doesn’t mean the gnats in your neck of the woods couldn’t be tricked into bellying up to the cast-iron flower buffet if yours happens to flower.

An evergreen perennial, A. elatior grows to about three feet tall and wide, but usually stays smaller indoors. It doesn’t have a central stem, but rather, each leaf emerges from the rhizome underground.

The scientific name Aspidistra is Greek for “shield” and elatior is Latin for “taller,” a moniker which is used to denote the fact that this plant has tall, lance-shaped leaves.

It looks somewhat similar to a hosta, which makes it ideal if you want to bring the look of that perennial favorite indoors.

If you decide to grow it outdoors, it can survive in USDA Hardiness Zones 7 to 11. If you struggle with deer devouring your hostas, this is a good alternative since deer ignore them when tastier food can be found.

Cultivation and History

The Aspidistra genus, which includes about 100 species, was first described by botanist John Bellenden Ker Gawler in 1822 in the Botanical Register.

Over the next few decades, the elatior species gained popularity and became more widely available in the UK, and later, in the US.

When we say thatA. elatior became popular, that doesn’t quite describe the following that it amassed. For a specimen that only grows wild in a few places in Asia, it certainly took the Western World by storm.

In Edwardian and Victorian homes it became a symbol of a nice, middle-class life in the same way that we may refer to having a home with a white picket fence today.

The fact that it could withstand the less-than-ideal conditions in homes during that period – which generally included dim lighting, and poor air quality thanks to coal and gas lighting and heat – undoubtedly contributed to its popularity.

The Aspidistra craze put it right in the sights of several artists.

George Orwell wrote a novel that namechecked the ubiquitous plant. In “Keep the Aspidistra Flying,” Orwell critiques the constant chasing of money and status, writing that middle-class social climbers of the time wanted nothing more than “to settle down, to make good, to sell [their] soul for a villa and an aspidistra!” and that “they ‘kept themselves respectable’ – kept the aspidistra flying.”

The protagonist Gordon Comstock even tries to kill his own specimen by adding salt to the soil and burning it with cigarette butts, but he finds the thing is impossible to kill.

Horror writer William Fryer Harvey offered his own take on the cast-iron plant in a short story called The Man Who Hated Aspidistras about a man haunted by the unkillable plants.

Scottish painter Samuel Peploe madeA. elatior the subject of several of his post-impressionist oil paintings in the 1920s. Singer Gracie Fields wrote a comedic ode to the Aspidistra in 1938 with a song called “The Biggest Aspidistra in the World.”

But as with anything that rides high in the arms of popularity, it eventually fell out of favor.

When I mentioned cast-iron plants to a fellow plant-loving friend, she remarked that her grandma had lots of them but she never sees them around anymore. That’s a wrong I believe should be righted.

Propagation

Because of the aforementioned unusual method of pollination, which isn’t highly successful even in the wild, seeds aren’t available.

That’s okay, because even though people are no longer writing musical homages to cast-iron plants (that we know of), they’re still widely available.

Plus, if you can get your hands on one, it’s incredibly easy to make more of them through division.

From Divisions

To divide, the first step is to remove it from its container and gently remove as much of the soil as possible. If you need to use a gentle stream of water to wash away stubborn soil, feel free, but make sure it’s lukewarm.

Then, find a natural division between the stems. So long as you are able to include a piece of the rhizome, the plant will likely continue to thrive, so don’t feel like you need to split it right down the center.

Use a clean pair of secateurs to cut through the roots and rhizome, and try to include at least one leaf. Even if you don’t, your plant will still send up new growth, so long as you include a node. That’s the little nub where a leaf or root will emerge from the rhizome.

Replant the parent in its container with some fresh soil and place the new division in its own pot with fresh soil. The rhizome should sit about an inch below the top of the soil, with the side where the leaves emerge positioned at the top.

Water the soil well, and keep the soil moist but not wet until new growth emerges.

From Seedlings/Transplanting

Keep an eye out at nurseries and home goods stores for cast-iron plants, bar room plants, or Aspidistras. They can be labeled under any of those names.

Once you find one, bring it home and place it in a decorative pot with good drainage.

Choose a pot that is one or two sizes larger than the nursery pot. These plants don’t need massive containers, but if you provide them with more room, they will expand in size.

A container that is a few inches wider than the base of the plant is ideal, but you can also grow it in a larger container so you won’t have to worry about buying a new one.

Cast-iron plants can live in a three-gallon container for their entire lives. Just make sure whatever container you select has drainage holes.

And becauseA. elatior has roots that grow near the soil surface, you can use a shallow container. For a young plant, you can get away with just six inches in depth, and for a mature specimen, nine inches will suffice.

Fill the bottom of the new container with potting soil so that the plant will sit at the same height it was in its nursery container.

You don’t need to use special potting soil, anything you pick up at the store will do.

I’m personally a fan of Tank’s-Pro Potting Mix because it contains a 50:50 mixture of coconut coir and compost, which provides water retention, drainage, and nutrients that will help most plants thrive.

Tank’s-Pro Potting Mix

You can grab a 1.5-cubic-foot bag at Arbico Organics.

Remove the plant from the nursery container and gently remove the soil from around the rhizome. Place it in the new container and fill in around it with soil.

Water well to settle the soil, be sure to empty that saucer after 30 minutes or so, and add more soil if it settled more than an inch.

How to Grow

The challenge with some tropical houseplants is that they have a low tolerance for temperatures beyond a certain range, particularly when it comes to cool temperatures, and they need to be kept humid.

Most homes have dry air, thanks to air conditioning and forced-air heating. ButA. elatior doesn’t mind dry air, low light, or even caretakers who are less than diligent about watering.

Don’t tell anyone I told you this, lest I be labeled as a neglectful plant parent, but I forgot to water mine for a month one time. I put it in my studio in the backyard and forgot about it. When I finally remembered, I raced out there to assess the damage, and it was sitting there like no time had passed at all.

Keep it out of direct sun, provide water once the top inch of soil dries out, maybe wipe the leaves to remove any built-up dust, and you can pretty much forget about this plant.

In other words, your approach should be decidedly hands-off. It thrives on being ignored.

You can keep the plant in a dark room and water less often, but this will come at the expense of new growth. Direct sunlight and heat will burn the leaves.

Unlike some houseplants, which you should water until the liquid runs out of the drainage hole, you should stop watering once the moisture has penetrated the top six inches.

The rhizomes of this plant grow right along the surface of the soil, and watering deep will just be wasted or contribute to root rot. On the bright side, that makes these plants excellent candidates for growing in shallow containers.

If the tips of the leaves start to turn brown, reduce the amount of water you’re providing, especially if it’s winter. Plants need less moisture during the winter dormant season.

A lot of plants also form brown tips when the humidity is too low, but with Aspidistra, too much water is more likely to be the problem.

While it can survive in temperatures as low as 35°F, it will go dormant once the temperatures drop below 50°F.

If you repot every few years (as we will discuss in just a bit), there is no need to fertilize. Feel free to add some houseplant fertilizer diluted by half in the spring and summer, if you want.

Growing Tips

- Keep out of direct sunlight

- Water when the top two inches of soil dry out

- Wipe the leaves every few months to remove dust

Pruning and Maintenance

Because cast-iron plants stay fairly petite, you don’t have to continually repot them in larger containers. You should, however, refresh the soil every few years.

This applies to any container-bound plant. As soil ages, it compacts, the nutrients leach out, and it can become hydrophobic.

To repot, remove the plant from its container and brush or wash away as much of the soil as you can. Place new soil in the container and place the plant back in place. Fill in around it with more fresh potting soil and water well.

Trim away any yellowing leaves, or any leaves that you just don’t like the look of.

If it grows too large for your liking, feel free to divide away.

Cultivars to Select

This plant is often sold under its generic common name, as you’ll find at places like Nature Hills Nursery, but don’t let that hold you back from seeking out some of the stunning cultivars that you can also find out there.

Cast-Iron Plant

There are cast-iron plants that are speckled in star-like splotches, and others that look like they’ve been painted with a watercolor brush.

For instance, ‘Asahi’ has a stunning white stripe that looks as though it was painted down the top third of each leaf. ‘Ginga Giant’ has dark green, wide leaves covered in bright yellow spots.

To learn about all the best aspidistra options available, check out our guide. (coming soon!)

Managing Pests and Disease

Honestly, I’m including the pests and diseases on this list because it is theoretically possible that your plant can be impacted by them.

But it’s far more likely that you’ll have problems with sun scorch or soggy roots from overwatering, if you do encounter any issues.

Insects

It’s rare for insects to attack cast-iron plants, but if they do, they usually won’t kill them. That is, unless it is already weakened from overwatering or sun exposure.

Scale

There are numerous species of scale insects in the Hemiptera order that will feed on houseplants. Armored scale is rare, but other types can be fairly common.

With a large enough infestation, they can cause wilting and yellowing of the leaves. When you look at an infested plant, you’ll notice little lumps on the stems and undersides of the leaves. Insecticidal soap can help you to get an infestation under control.

Our guide to scale provides some excellent tips.

Spider Mites

Red spider mites (Tetranychus urticae) are another common variety of houseplant pest. Rather than seeing symptoms on the plant, you’ll likely notice the fine webbing that these spider relatives leave behind.

Neem oil and insecticidal soap are both effective treatment options. Our guide has more information on how to deal with spider mites.

Disease

There’s just one disease to watch out for, and it’s pretty easy to avoid. Meet the dreaded root rot.

Root Rot

Root rot can be caused by various fungal pathogens, species ofRhizoctonia, and Fusarium, and water molds in the Pythium and Phytophthora genera, or by simply drowning the roots with too much water.

The latter is far more common than the former, but since you need access to a lab or a good microscope to know what’s causing the problem with certainty, you’ll need to treat for both causes if you spot signs of this ailment at home.

The first step is to remove the plant from its pot and remove all of the soil. If the soil is soggy and smells musty, you can be fairly certain that you’ve been overwatering.

Next, trim away all of the soggy or mushy roots. Clean the container using a mixture of one part bleach and nine parts water. Repot in fresh potting soil.

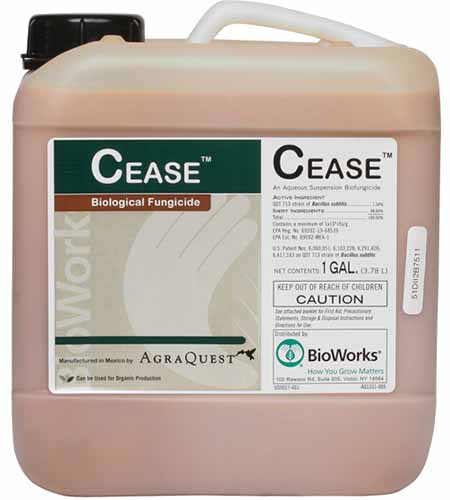

CEASE Biological Fungicide

Finally, treat the new soil with a product containing Bacillus subtilis such as CEASE Biological Fungicide, following the manufacturer’s directions. This will help to address all kinds of pathogens that can cause root rot.

Grab a gallon or 2.5-gallon container of CEASE at Arbico Organics.

Best Uses

Aspidistra shines as a potted specimen, with or without other plants. It can be a centerpiece to lower-growing species, or it can be planted alone.

It does well in both deep and shallow containers, and larger cultivars do best as floor plants. Don’t forget that you can use them outside as non-invasive ground covers in suitable zones as well.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Herbaceous evergreen | Flower/Foliage Color: | Purple (rare indoors)/green, green with yellow, green with white |

| Native to: | Japan, Taiwan | Tolerance: | Drought, low humidity, low light |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 7-11 | Maintenance: | Low |

| Exposure: | Bright, indirect light | Soil Type: | Potting soil with sphagnum moss and rice hulls/vermiculite |

| Time to Maturity: | 5 years | Soil pH: | 6.5-7.5 |

| Planting Depth: | 1 inch (rhizomes), same level as container (transplants) | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Height: | 3 feet | Uses: | Potted specimen |

| Spread: | 3 feet | Order: | Asparagales |

| Growth Rate: | Medium | Family: | Asparagaceae |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Genus: | Aspidistra |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Scale, spider mites; root rot | Species: | Elatior |

Every Bit as Tough as Their Name Suggests

Even the brownest thumb can succeed with cast-iron plants. It doesn’t matter if you have killed every other houseplant you’ve tried so far, or if you’re just sick of pampering your potted pals, A. elatior will become your new best friend.

That’s not hyperbole. Any plant that could thrive in the dark interiors and polluted air of Edwardian and Victorian homes can certainly survive whatever you throw at it. Just don’t leave it in direct sun or a puddle of water, and you’re good to go.

Does the cast-iron plant inspire you to write songs and stories about it? Okay, maybe not, but let us know in the comments what cultivar you’re growing. Each seems to be more beautiful than the last.

Now that you’ve boosted your houseplant growing confidence, you might be excited to grow a few more easy-care varieties. If so, give the following a read next: