[ad_1]

A finite description of sacred architecture is, by its nature, almost impossible to satisfactorily articulate. How do you give form to religion and to the spiritual, that which transcends the material world, existing outside of time and space? In architecture, the sacred can perhaps only be hinted at by a ray of light moving across a wall, the soft rounded edge of a pew, or a choir of resounding voices coming together in prayer or song. The sacred asks much of architecture: to be art; to be poetic; to be beautiful; to inspire awe; to embody ambiguity; to give rise to sensations beyond words or descriptions.

Religious buildings, symbolically expressing their status, have traditionally been located at town and city hearts, around which secular activities have taken place. Their “sacredness,” however, does not come from their symbolism or location; instead, it is created by quiet sanctuary for those wishing to commune with God, alone and with others. It is an experience that is slow and deep, penetrating rational thought and reason to speak to the subconscious and emotion.

Contemporaneous with the commission for the Punchbowl Mosque, Angelo Candalepas was approached by members of the community-based Church of the Living God because their existing premises no longer met their needs. An offshoot of a local Baptist church, the Pentecostal organization has a strong family and immigrant parishioner base, delivering religious fellowship in tandem with community support and welfare. They required a hall for services and community activity for 350 people, with the ability to hold 520 for special occasions; secure and accessible crisis accommodation; and off-street parking. It is not a wealthy community and the budget was tight. For the Greek Orthodox Candalepas, who talks comfortably of spirituality, this complex, mixed-use suburban building was an opportunity to explore the sacred.

The building draws strength from the confident presence of refined, bespoke details and off-the-shelf products in unrefined materials.

Image:

Rory Gardiner

Architecturally and metaphorically, the building embraces the duality of the material and spiritual worlds. Externally, it makes an active contribution to its surrounds; its interior sacred core offers silence. Recalling French sociologist Émile Durkheim’s view that religion was defined by the distinction between the sacred and the profane, the building draws strength from the confident presence of refined, bespoke details and off-the-shelf products in unrefined materials.

Located on a wide road with an eclectic mix of medium-scale apartments leading from Hurstville’s town centre, the structure could, at first glance, be another apartment block. But its civic presence provides a clue to its alternate purpose. The building is set back, with steps, a ramp and an elevated garden bed contributing to the suburban streetscape while addressing the client’s security requirements.

Each elevation is unique and speaks to the adjacent context. The street facade is confident and animated in depth and form. It clearly states its three generous storeys, with vertical elements placed within expressed concrete floor planes. Concrete sewer pipes, halved lengthwise and deployed as pillars, have been painted with a matt white finish that holds and softly reflects light, even on a cloudy day. In addition to reducing sight lines into the building from the street, the repeating pillars provide beauty and evoke the sublime. A courageous flying roof sits above one end of the building – a civic or divine gesture? Large, galvanized steel drainpipes stand apart from the building and carry the eye upwards. These combined geometric elements simultaneously speak a universal language and visually link to the decorative components of the surrounding apartments from the 1970s and 1980s: the new, making sense of the existing.

The rear facade is likewise bold, full of depth and shadow created by blade-like structural columns scaled relative to the apartments behind. One short facade steps back to offer a paved courtyard with a single tree, creating a dialogue with a red-brick bungalow currently used by the organization. The building exposes its true size on the opposing end above the carpark entrance, and this unarticulated facade is the most jarring in its non-residential otherness.

This mixed-used building is laid out on a grid that gives perceptible order in plan and allows spatial complexity in section. The double- to triple-height place of worship and community multi-use activity forms the central spine around which ancillary spaces wrap. The sacred sits at the core – literally and figuratively. On the ground floor, the amenities run the length of the building, opening onto a cloister to the front and a landscaped garden to the rear. On the upper two floors, apartments for the church community and its guests sit along the facades.

The welcoming entry is a carefully choreographed sequence across subtle physical thresholds accompanied by gradating light. Wide steps from the pavement lead the visitor under an exposed concrete canopy to beautifully detailed double doors. Externally sheeted with fibre cement, they open outward to reveal internal timber veneer and guide guests to the semi-enclosed lobby, where the concrete sewer pipes create the cloister. From here, a matching set of full-height doors leads into the main worship space. The doors have curved, sensuous edges and long, vertical timber handles comfortable to grip.

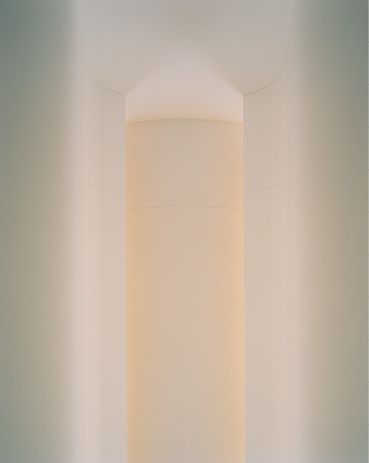

Reflections from hidden gold paint cause the lightwell to glow – a “moment of pause and awe.”

Image:

Rory Gardiner

On entering, the eyes are drawn upward to a vase-shaped lightwell that emanates a warm glow created by reflections from hidden gold paint. The light is drawn down, caressing the curved vertical surface. It is the moment of pause and awe. The body is then drawn into the space and pivots to see the altar. The roof, three storeys above the sanctuary, appears to hover, as light from an unknown source softly seeps across the ceiling and over the walls’ curved tops. A narrow glass strip between the roof and altar wall creates a linear glow, an extra treat for the translation booths located on the second storey. Light touches the floor, illuminating the altar and recessed space for preaching and playing music.

While there are the obvious sacred gestures, the strength of the architecture is in how it achieves silence and stillness in these spaces – through its planning, limited material palette and ineffable atmosphere.

The apartments on the second and third floor follow relatively standard planning models but have been afforded spatial generosity – high ceilings and wide corridors. Sensitivity to security and privacy appears to have influenced sill heights, screening bars and balcony enclosures, which feel somewhat defensive. These are spaces for multiple occupancy for emergency and long-term use, and the character and life will come from those occupants.

From the number of beautiful hand drawings and designs produced, it is evident that this building is the product of a long, highly involved process for both architect and client. There is clear aspiration on the part of the architect to create a sacred architecture beyond the practical requirements of the client and fabric of the locale. The building elevates the relatively standard suburban context and reflects another future vision of itself, giving a new scale, aesthetic, material and spatial presence to this local religious organization and its congregation. Only time will tell how people will inhabit and come to identify with it, and how it might influence the development and streetscape of its place.

— Kate Goodwin is a curator, writer, cultural leader and educator. She is a professor of practice in architecture at the University of Sydney and formerly head curator of architecture at the Royal Academy of Arts in London.

[ad_2]

Source link