[ad_1]

The story of Lobster Bay House is as much about its architect, Ian McKay, as it is about its client, renowned photojournalist David Moore. The lives of McKay and Moore were intertwined, both professionally and personally: as colleagues, they shared offices in North Sydney, while McKay was also stepfather to Moore’s children. Lobster Bay House, completed in 1972 and considered to be one of McKay’s best residential designs, marks the evolution of the relationship into that of client and architect. Designed as a holiday house for Moore and his children, it is an intricately crafted shelter that pursues an elemental occupation of a dramatic rocky site.

McKay (1932–2015) was part of the Sydney School, a group who celebrated the use of common and natural materials and who searched for an architecture that reflected the local environment and landscape character. He established his own practice in 1960 and his early career included a four-year association with Philip Cox. Their collaboration resulted in two Sulman Medals, awarded to public buildings by the New South Wales chapter of the Australian Institute of Architects: St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church in Leppington in 1963 and the C. B. Alexander Presbyterian Agricultural College in Tocal in 1965. After McKay and Cox went their separate ways, McKay continued to pursue residential design throughout his career.

Moore was no stranger to the Sydney School architects. His early career included time in celebrated photographer Max Dupain’s studio and, later, his own work spanned architectural, commercial and now iconic imagery of Sydney’s foreshores and harbour. Moore used to take his four children on camping trips to the north and south of Sydney and, as the years passed and the load of camping paraphernalia, surfboards and boogie boards grew, he decided to seek out a more permanent bush retreat.

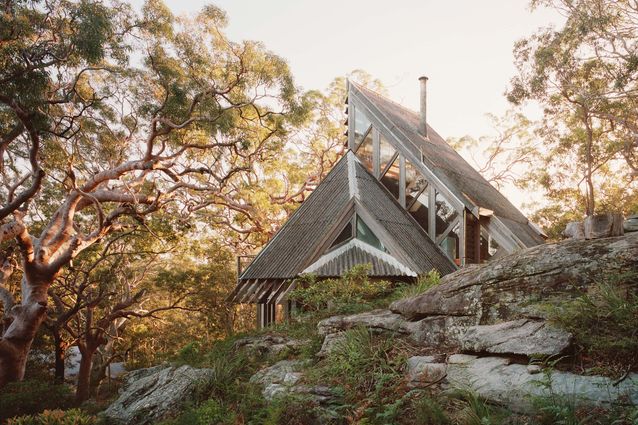

Located in Pretty Beach on the New South Wales Central Coast, Lobster Bay House was designed as a tranquil holiday home in the bush.

The eventual site for the house was found by McKay and purchased by Moore in 1968. Located two-hours north of Sydney and bordering the Bouddi National Park in Pretty Beach, the site straddles a ridge above Lobster Beach looking out over Broken Bay. Moore was conscious of his role as custodian of the unspoilt bush block and its established forest of angophora costata trees. In line with his desire for a shelter within the bush, his brief to McKay was to create a building akin to an “insect sitting upon a rock.” The first few iterations of the design, with inboard bathrooms bordered by sleeping quarters, were rejected, and the eventual design is thought to have been guided in its form by Moore himself. The result was a layout with a main living area bordered by a kitchen and deck, flanked by bedrooms and bathrooms that fan out across the rock. McKay resolved this into almost perfect symmetry, shifting the children’s bedroom into a loft over the central living area – a suspended, tiered structure of bunks accessed at each end by pipework ladders with timber treads.

The house sits perched high on a rocky outcrop. With the wings of its roof battened down to withstand the prevailing south-westerly winds that howl up the hillside, the building is strongly evocative of both a tent structure and its entomological origins. The symmetry is broken only for key moments to distinguish entry points. The deck gives way in one corner for a large angophora, which is now protected by a balustrade but which was originally bounded by a bench seat, thrillingly wrapped around the perimeter of the trunk. These touches with nature are continually curated at Lobster Bay House. A series of stone steps, individually hauled into position by Moore, wind up from the access road to the back door (though it is used as the main door). The prominent, steeply pitched roof is the building’s primary external form, and its distinctive skin of corrugated asbestos-cement sheet is now covered in lichen, allowing the home to blend in perfectly with the site’s weathered sandstone boulders. In later years, when the dangers of asbestos fibres became known, McKay held this material choice as his only regret in the execution of the project, its beauty paired uncom-fortably with its hazardous legacy.

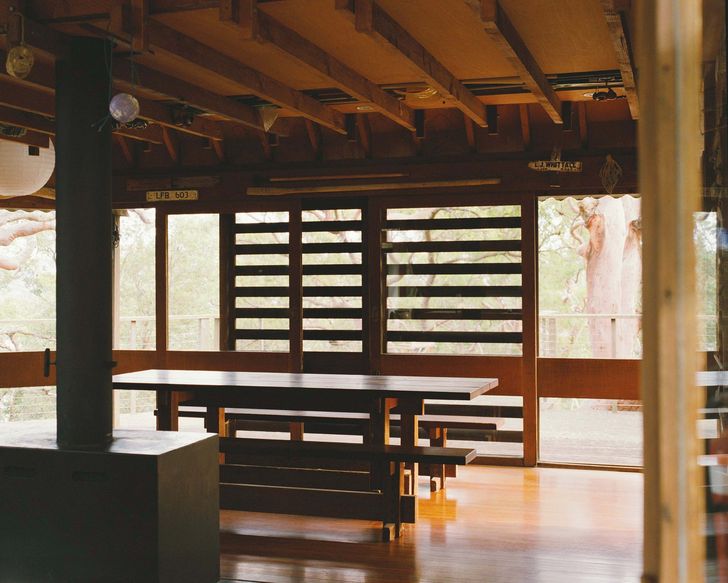

While the exterior of the building focuses on shelter and protection, the interior is cosy and calm, lined with plywood, western red cedar and expressed sawn Oregon beams. The building is entirely defined by its structure: two timber trusses propped in an ‘A’ frame arrangement. The ‘A’ frame is flanked by the two wings, which accommodate the symmetrical arrangement of bedrooms and bathrooms tucked beneath. Lovingly constructed by a local builder, Peter Velling, and foreman/carpenter Jack Coster, the house – initially thought to be buildable in six weeks – was completed over the course of a year from 1971–72.

The plan is simple and symmetrical, with centrally located living spaces flanked by bedrooms and a wide deck.

When inside Lobster Bay House, you are aware of how considered and complete the building is. Deceivingly simple in plan, it has a complex section to suspend the loft structure. The provision of windows and hatches along the webs of the truss creates unexpected spaces and moments at each turn. The quality is distinctively Japanese in the consideration of joins and the hierarchy of timber members. The removal of one element would seemingly render the whole incomplete and unsupported.

When Moore decided he was ready to part with the property, his children united to take over its care while continuing the family’s use and patronage of the house. Internally, the walls are covered in found objects collected from Lobster Beach, collated and nailed in place. Coat-hanger portraits hint at rainy-day activities during summer holidays. A charcoal drawing covers the original location of the angled chimney flue, which was removed due to the impracticality of walking below it and its tendency to fill the room with smoke. The richness added to the interior by years of family use make you understand the Moore children’s desire to remain its custodians. They have, in turn, spent many years addressing maintenance issues, resolving roadway access and diverting stormwater to ensure the protection and longevity of the property.

This is a building that few would dare to build today: small in size, sitting lightly in its bush landscape, turning its side to the expected views and providing minimum comfort. It is as much about what is built as what is unbuilt. Mostly, though, it is about experience. You feel the unevenness of the boulders (and the weight of your groceries) as you climb up to the house. At night, tucked beneath the building’s wings, you hear the wind rattle the treetops and you are woken by the cacophony of birds whose home of branches the house sits within. The house connects its inhabitants to the land on which it sits, allowing them to discover the bush while camouflaging itself in plain sight.

The prominent, steeply pitched roof is the building’s primary external form, and its distinctive skin is now covered in lichen, allowing the house to blend in perfectly with the site’s weathered sandstone boulders.

[ad_2]

Source link