The glittering images of the envisioned Saudi city NEOM, shared publicly in late July, quickly circulated around various social media platforms. Many commented on the formal and visual similarity the megalomanic vision has to an array of linear-city precedents in the history of architecture, from Michael Graves and Peter Eisenman’s proposal for a linear New Jersey in 1965; to Rem Koolhaas’s infamous graduation thesis, “Exodus, or the Voluntary Prisoners of Architecture” from 1972; or, most obviously, to Superstudio’s late 1960s critique in the form of the Continuous Monument. The slew of images and videos giving architectural form to Mohammed Bin-Salman’s latest lunacy do more than evoke an array of architectural fantasies and propositions. Rather, in ironical fashion they point precisely to a disregard of the history of architecture and bring to mind Karl Marx’s observation on the repetition of world events: “First time as tragedy, and again as farce.”

Indeed, the 170-kilometer long, 500-meter-high, and 200-meter-wide mirrored spectacle of a city, which is somehow supposed to be sustainable and emit no carbon, lends itself almost too easily to criticism, as well as to the observation that much of postwar and Cold War culture is having a strange revival in recent years. Not to be disregarded, these observations point to the inherent nature—and limits—of human imagination, and the difficulty to step beyond certain paradigms of culture and progress. And yet to disregard NEOM as the mere megalomaniac fantasy of an authoritarian ruler would repeat, to some degree, Marx’s observation, this time on the part of the critic.

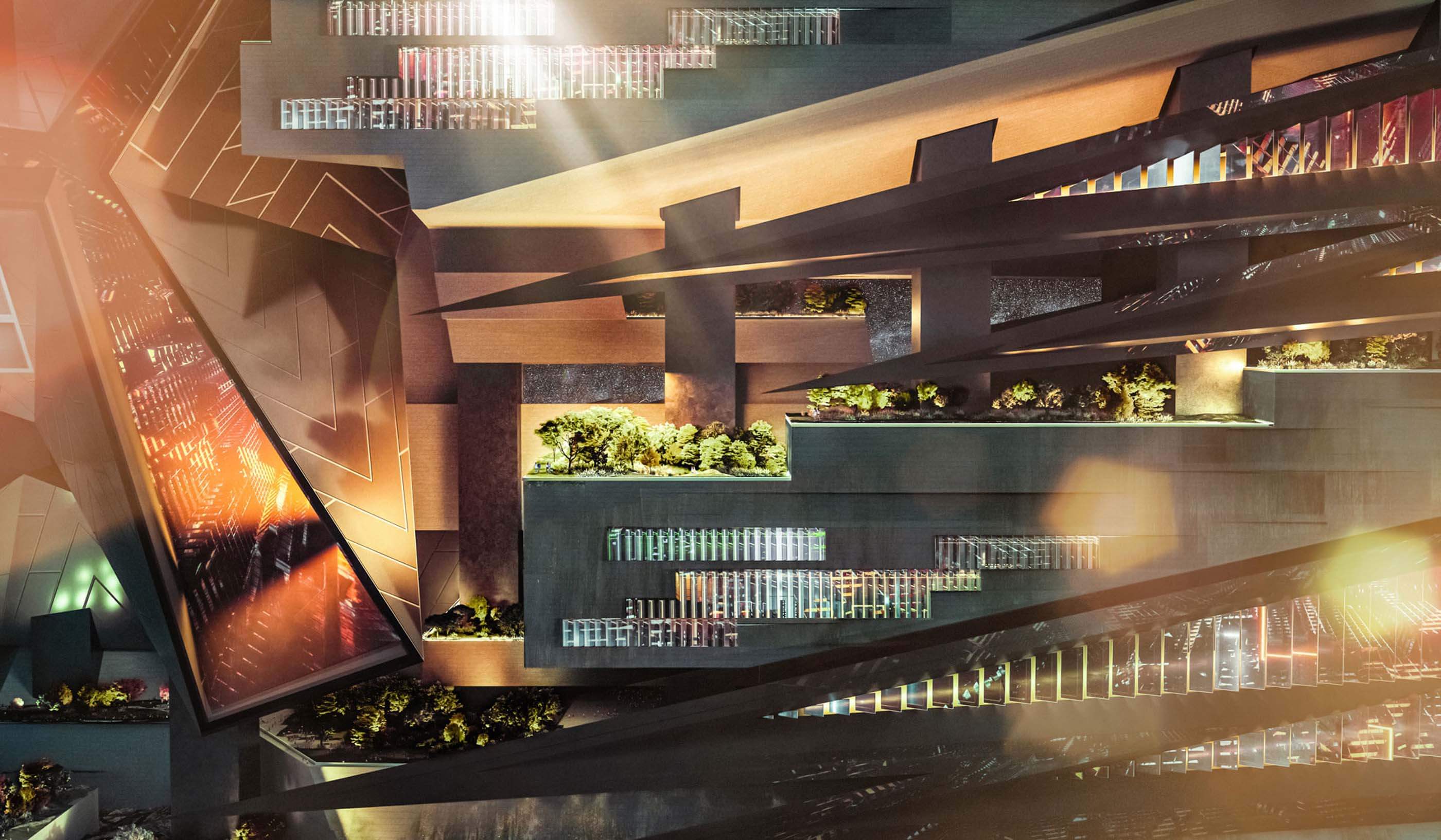

If anything, NEOM, precisely because of its audacity, offers a valuable lesson not only to architects and architectural historians, but to anyone who is concerned with the future of humanity as we face the climate crisis. Not to discard its potential execution—or the somewhat tragic realization that a portion of the design has been given to erstwhile rule-breaker-turned-techno-positivist Pritzker Prize winner, Thom Mayne of Morphosis—the images of NEOM, when taken seriously, and as a first step towards realization, reveal not the future of humanity, but the present state of our struggle to imagine a future at all.

In 1984, before a backdrop of rising nuclear fears, Frederic Jameson suggested in “Progress or Utopia; Or, Can We Imagine the Future?” what science-fiction visions of the future can offer. Though Jameson wrote specifically about science fiction as a literary genre, the nature of NEOM and the cultural references embedded in its representational images can indeed be examined as a science-fiction text. Stepping beyond the examination of sci-fi narratives as utopian or dystopic representations of possible futures, Jameson noted the relation between the representational imagination of the future and the historical conditions from which science fiction emerged as a genre. The authenticity of science fiction, for Jameson, lies not in its visions of the future, but in its dramatization of “our incapacity to imagine the future.” When inspected deeply, and beyond their surface-level, representational, and ideological appearances, science fiction narratives “succeed by failure” and transform “into a contemplation of our own absolute limits.” Their deeper function, according to Jameson, is to challenge our relationship with the present by transforming it into the past of “something yet to come;” to take the present, which we cannot fully grasp because of its incommensurability, its complexity, its unwieldly scale, and make it into a past so that we can think of it historically.

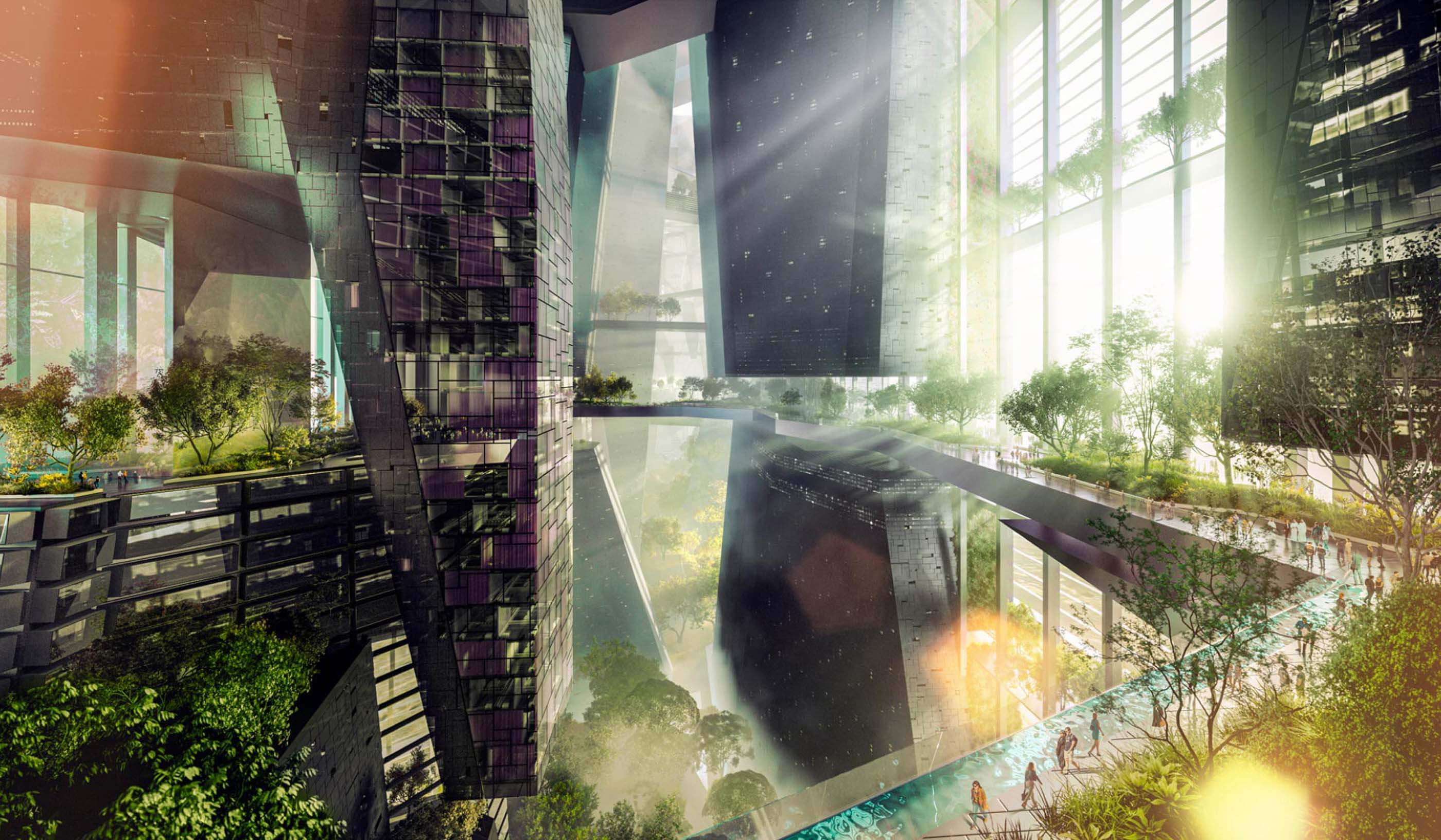

How then, does the fantastical vision of NEOM defamiliarize the present? Better yet, what kind of vision of the present does this vision of the future afford? For one, it is the sheer magnitude of the proposal that in fact exposes and corresponds to the scale of the threat it seeks to face. In its unabashed clarity, the NEOM line does not offer a complex city, but rather consolidates the “massively distributed” climate crisis—what Timothy Morton calls hyperobjects—into a supposedly localized and seemingly legible architectural form. By concentrating nine million humans—we have yet to talk about which particular and certainly extremely wealthy humans would be able to live in this linear palace, given the yachts docked at its Red Sea coast—within a shiny and reflective ductwork, it exposes our inability to confront the climate crisis with schemes that would do more than reflect and represent its sublime qualitative magnitude; our incapacity to grapple and confront its defining qualities as a crisis that defies borders, that is global by its very definition, that is pervasive and diffuse.

What of nature? The NEOM presentation begins with a premise that one cannot but agree with, though with certain reservations and qualifications: “For too long,” it goes, “humanity has existed within dysfunctional and polluted cities that ignored nature.” In response, NEOM offers not only to “protect” nature but to “enhance” it. This nature, we should note, is the Rub’ al Khali, or the “empty quarter”—one the largest sand deserts in the world: a landscape that is anything but empty, which is in fact inhabited by various tribes as well as plants and animals. As historian Diana K. Davis noted, the perception of the desert as an uninhabitable and inhospitable wasteland has been long constructed by temperate-climate Westerners who have sought to green this and other arid lands. Indeed, and despite its declarations, that is precisely what NEOM does. With its reflective mirrored walls, and its interiorized, micro-climatic, conditioned, and allegedly sustainable environment, what NEOM offers is not a rethinking of the division between humanity and nature or the reconceptualization of the desert as anything but threatening, but rather its reinforcement.

Nature, however untouched, is not only to remain completely as a pristine exterior, it is to be reflected in the largest architectural edifice ever built, which ironically also announces its desire to disappear. Compiling and collapsing a multitude of aesthetic theories into one another, the NEOM line is perhaps the most radically postmodern architecture ever created. Its sublime scale incorporates a surface which turns the architecture itself into a picture frame through which a simulacrum of constructed nature can been viewed as picturesque. What the images of NEOM—rather than the actual city—reveal is not a vision of humanity in harmony with nature, but the contemporary inability to reconceptualize our relationship with an exterior that is guaranteed to become harsher with every season passing by.

It would almost be redundant to note the lack of information about what the construction and future of The Line will entail. The ecological disturbances and displacements, the cost of human and non-human lives, the carbon footprint stemming from the manufacture and delivery of construction materials, including, if we take the metrics seriously, an estimated 170 million square meters of glass. Not least among these is a question of governance, especially in the context of the Saudi government.

Once again, NEOM should not be dismissed or criticized for what it offers—or does not offer—but rather for what the offer reveals. It is the inability of Western liberal democracies to mobilize themselves in the face of a crisis that they have not only caused and exacerbated, but that now threatens their—that is, our—progressive and liberal ideals. This, however, is not a call for an oppressive world government that would tackle the climate crisis with full force. Rather, it is a recognition, offered inadvertently by the likes of NEOM, that we live in a dichotomous reality in which authoritarian regimes can mobilize Western “experts,” knowledge, and capital in service of a supposedly magnanimous and innovative solution, while democratic countries are busy debating what should be done. NEOM thus, can perhaps be most aptly viewed not as a proposition, but rather as a Benjaminian allegory: an enormous mirror in which the desert by which we are surrounded is transformed into an image without substance; a glittering vision of the future through which the present’s ruins are seen more clearly than before.

Eliyahu Keller is an architect and architectural historian, and a founding faculty member of the Negev School of Architecture in Israel. He holds a Ph.D. in History, Theory and Criticism of Architecture from MIT, where he investigated the influence of nuclear apocalyptic culture on speculative architectural representation in Cold-War US.