Daphne odora

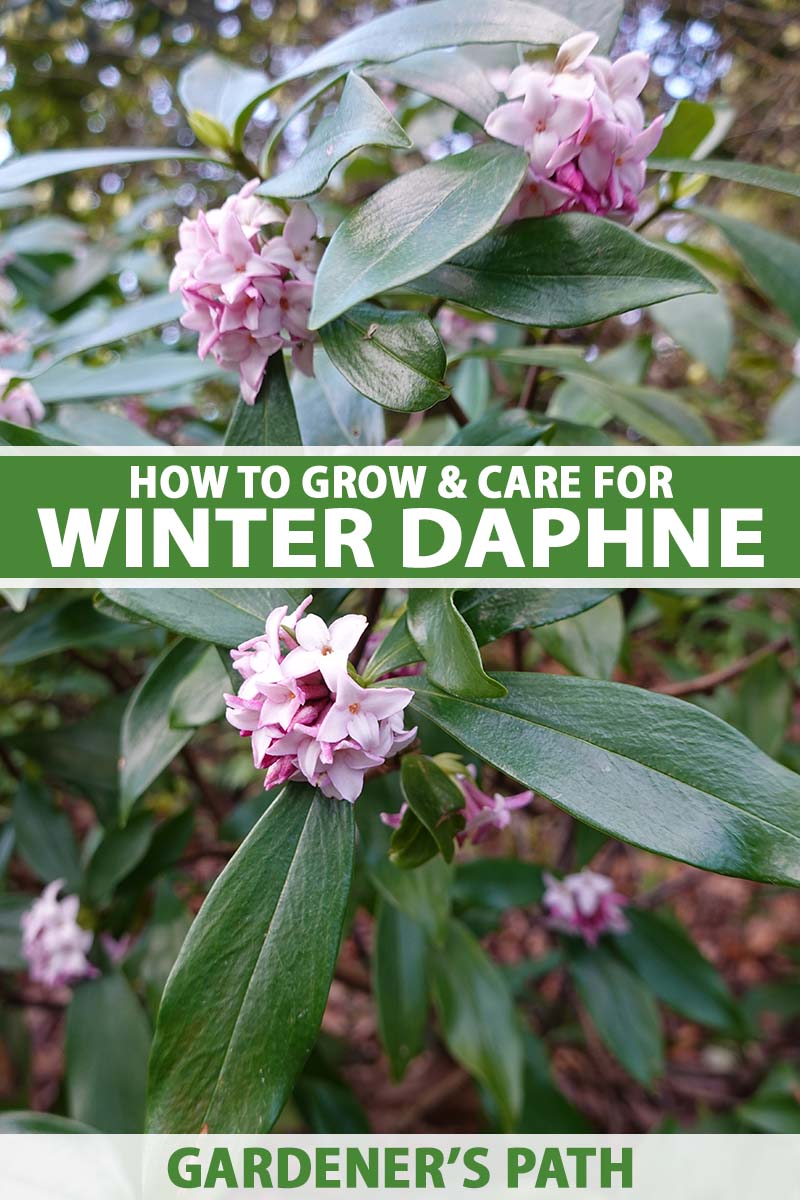

It might be small and demure, tucked away by the back door or under the eaves alongside a garden path, but you’ll never overlook winter daphne (Daphne odora) when it’s in full bloom.

The sweet, spreading scent of its delicate flowers will fill your garden and home, and you won’t want to miss a moment. That’s why it’s best planted as close as possible to your house so you can enjoy its rich spring perfume.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

In this guide, we’ll look at this plant’s likes and dislikes, why it’s known for being temperamental, and how to grow it in a pot as well as in the ground.

My grandmother’s name was Daphne, and my parents have always grown winter daphne in their garden in her honor.

I’ve just moved into an old farmhouse with quite a traditional cottage garden palette – think clipped hedges and standard roses – but the first plant my mother sniffed out when she visited was winter daphne.

It was hidden behind a line of shaggy boxwood bordering the path leading to the back door.

Mum had caught the scent on a still day while standing a good 10 feet from the plant, and that’s a big clue as to why people love this woody shrub so much, despite its relatively short lifespan.

Here’s an overview of what we’ll cover in this guide:

What Is Winter Daphne?

Winter daphne, also known as sweet or fragrant daphne, has the strongest-smelling flowers of more than 90 different species belonging to the Daphne genus.

The evergreen, mounded woody shrub has light to dark green leaves with a leathery gloss and extremely fragrant flower heads. It can grow from two to four feet wide and four to six feet high.

It grows best in partial shade in Zones 7 to 9, out of the blast of the summer sun, in humus-rich soil. It can be grown in a pot, although this can be tricky – read more below under Container Care.

There are also some exceptions to the rule. In the Denver Botanic Garden, for example, the more cold-hardy D. odora ‘Zuiko Nishiki’ thrives in Zone 6 conditions in their sheltered Rock Alpine section, growing in dry, gritty soil.

In shades of deep red to rose to white, one- to one-and-a-half-inch blooms are produced in clusters made up of 10 or so tiny florets. They can bloom as early as late January to May in Zones 8 to 9, and from March or April to May in Zone 7.

Cultivation and History

In the wild, D. odora sits in the dappled shade of taller forest trees. Its wonderful scent has made it a garden favorite in its native China and Japan for thousands of years.

In the West, it became popular among Victorian gardeners in the 1800s in the UK where it was often kept as a houseplant.

Daphne is the Greek name of a mythological nymph and means “laurel” while odora means “fragrant.”

A Note of Caution:

All parts of D. odora and all other daphne species are toxic to people, pets, and livestock. Some exhibit skin allergies when exposed to the sap so it’s advisable to wear gloves when handling these plants.

Rarely, D. odora may produce red berries after flowering which can look attractive to children. However, they taste extremely bitter which tends to make them less likely to be eaten.

If your plant does produce berries, remove and dispose of them immediately if you have children or pets.

Signs of ingestion in people and animals include ulcers or blisters in the mouth, excessive drooling, vomiting, and bloody diarrhea. Toxic effects may include blisters in the esophagus and stomach, seizures, coma, and death. However, fatalities are extremely rare.

Propagation

Commercial growers graft plants but the process is complex and beyond the scope of this article.

You can grow winter daphne from seed. However, most D. odora varieties rarely produce them. If yours does, germination is notoriously unreliable and some report it can take up to two years.

In contrast, it’s easy to propagate these plants from cuttings or by layering stems.

Be warned, rooted cuttings can be slow to grow and may take up to two years to flower, so most gardeners opt to buy transplants from a nursery. The difficulty in propagating daphnes is why they tend to be pricier than other similar-sized shrubs.

However, ask anyone who’s had one and they’ll reassure you – the contribution they make to late winter and early spring gardens is worth the investment.

From Cuttings

Take cuttings in early to midsummer. Stems should be taken from the current year’s growth that had not yet flowered. Only take cuttings that are healthy-looking, undamaged, and firm.

You will need rooting hormone powder and a four-inch nursery pot or peat pot for each cutting, filled with a free-draining, sterile seed-starting or rooting mix. Water the soil well, so it’s damp before you add the cutting to it.

Use sharp, sterile secateurs or snips to take a six-inch cutting – snip just below a leaf node into the woodier part of the stem. Remove the leaves from the lower half and any soft tips at the top until two to four leaves remain.

Bontone II Rooting Powder

Dip the cut end in rooting hormone powder like Bontone II Rooting Powder, available from Arbico Organics.

Tap the stem gently to remove any excess powder. Use a dibber to create a hole, then push the end into the mix until half the stem is buried, almost to the level of the lowest leaves. Firm the soil around the cutting.

Place inside a clear plastic bag. Loosely tie the bag so there’s high humidity with some air circulation. Sit in a moderately warm, moderately bright spot such as on top of the fridge.

Check the soil and bag daily. You want moist but not waterlogged conditions.

Roots should develop in a few weeks, but sometimes it can take as long as 10 weeks. To check, ever so gently pull on the cutting to see if there’s resistance.

Once there are roots, open the bag to allow more air to circulate. After a few weeks, remove the bag and place the cutting in a spot with direct morning sun. Allow the soil to dry out to an inch or so deep before watering.

Transplant into the garden once it has developed healthy, strong new foliage, which may take up to a year depending on the variety. Choose its forever location in the garden carefully – read more about site selection under How to Grow below.

By Layering

Stem layering mimics a natural process where stems that touch the ground take root.

You will need rooting hormone powder, a few handfuls of a potting mix that’s rich in organic matter like compost, peat, or coir; a scalpel or other sharp cutting tool; a steel garden staple or a piece of wire bent in a “U” shape; and a brick.

In spring, look for a young, healthy stem that is supple enough to bend and lay along the ground with little to no resistance.

Use the scalpel to remove a couple of sets of leaves on new wood, around six to 10 inches along the stem. Make a shallow nick just below a leaf node.

Mix the compost into the soil where the nicked stem will lay. Dig a little trench into the soil mix, place the stem in it, then pin it in place. Add a thin layer of soil just to cover it, then place the brick on top.

The stem may take up to 12 months to form enough roots to support it. Once the stem is showing strong foliage growth, cut it off on the side of the mother plant.

You can transplant it to a new spot, or better yet, leave it in place if the original plant is over five years old as it will be nearing the end of its life.

How to Grow

D. odora is a slow-growing, low-maintenance shrub that will grow outdoors in Zones 7 to 9, tolerating nighttime temperatures down to 10°F in a spot sheltered from cold winds.

Soil Preferences

It’s critical to plant winter daphne in the right conditions as its very sensitive root system doesn’t tolerate being transplanted. Sometimes even soil disturbance nearby can affect it.

Choose a spot with morning sun and light or dappled shade through the rest of the day. It must be protected from the bright midday summer sun and cold, drying winds.

Too little sun and flowering will be limited; too much and the leaves will burn.

Generally, it does best in slightly acidic to neutral soil with a pH of 5.5 to 7.0, although plants will sometimes tolerate slightly alkaline soil.

Ideally, soil also needs to be sandy, humus-rich loam. Most importantly, it must be well-draining. If anything is going to kill your daphne, it’s root issues, most commonly caused by poor drainage.

When planting out from a nursery pot, try to leave the roots in peace. If the pot doesn’t slide off easily, cut it off. If you don’t need to, don’t loosen or “tickle” the roots to spread them out.

Sit the plant ever so slightly above ground level so it has a little room to settle. Tamp the soil as you backfill around it so there are no air pockets.

If you have clay, dig a hole that’s two to three times larger than the root ball. Use some of the clay from the planting hole and thoroughly mix it with free-draining soil options such as composted bark, potting mix, and coarse sand.

The proportions will depend on your ingredients, but adjust until you have a loose, sandy mix.

Backfill into the hole so the plant is an inch or so above the original ground height and then mound the soil mix up around it.

Watering

Daphnes don’t like sitting in wet soil and are fairly drought tolerant.

If you’re not sure whether to water, err on the side of dry rather than risk making it too wet. Reduce watering during dormancy and leading up to bloom time.

It’s rare to need to water a daphne much over winter unless it’s in a particularly dry spot such as under the eaves of a building.

They do benefit from a long, deep watering during dry periods but check to make sure the soil is dry at two inches deep before you do it again.

It can be better to water by hand rather than using irrigation on a timer so you can judge the soil moisture yourself.

Mulch with a thin layer of leaf mold, or aged shredded wood or fine bark, but keep it away from the main stem.

Feeding

Mostly, plants out in the garden are self-sufficient and don’t need feeding. It’s different for those growing in a pot – read more in the Container Care section coming up.

If they do show signs of a lack of nutrition such as yellowing leaves, provide a light feeding of slow-release shrub or tree fertilizer.

However, note there are other reasons leaves may turn yellow, including poor drainage or drought.

If leaves turn yellow but have pronounced green veins, it’s a sign of an iron deficiency caused by soil that’s too alkaline. The cause may be lime you’ve added to the soil or the plant may be too close to newly-laid concrete.

Look for a fertilizer for acid-loving plants as these contain iron chelates, which will help raise iron levels.

Fertilome Chelated Liquid Iron

You can also use an iron chelate product such as Fertilome Chelated Liquid Iron, available from Nature Hills Nursery.

Espoma Soil Acidifier

Or, try a soil acidifier like Espoma Soil Acidifier Organic Supplement, also available from Nature Hills Nursery.

Growing Tips

- Plant in free-draining soil or in mounds of free-draining soil mix if you have clay.

- Choose a spot with morning sun followed by light shade.

- Let the soil dry out to a depth of two inches between waterings.

Container Care

Winter daphne can be grown in a container, but these plants are known for being “temperamental” thanks to their sensitive roots, which are more at risk of becoming too wet or too warm in a pot.

Choose a container that will last for the plant’s lifetime, based on the height and spread at maturity of the variety you choose.

You want to select one that is at least twice as wide as the root ball – or a minimum of 12 inches for transplants – and at least twice as high as it is wide.

There are several reasons for this:

- The roots need room to go deep

- Plant health suffers if the roots get too warm or too cold

- Your specimen probably won’t survive being transplanted due to root disturbance if it doesn’t like being in a pot

The pot must have a drainage hole or holes at the bottom. Don’t put anything in the bottom of the pot such as stones or mesh, as this will slow the flow of water through the soil and create soggy patches.

You may need to move the container to a drier spot in prolonged rain.

Use humus-rich potting soil. For good drainage, add 20 percent perlite, pumice, or crushed granite chicken grit, like this one from Chicken Heritage that’s available on Amazon.

Granite Chicken Grit

If the plant is showing signs of distress, such as yellowing foliage, the soil pH may be too high.

Be careful not to disturb the roots while planting. Try not to touch them – cut the nursery pot away if you’re having difficulty removing it.

Water deeply and add more potting mix if the soil level settles below the top of the root ball.

Place the container in a spot where the plant receives morning sun and dappled shade in the afternoon to keep the roots from getting too warm and to prevent burns to the foliage.

Allow the top two inches of soil to dry out between waterings. Drooping leaves can be a sign of dehydration, but they can also be a sign of too much water – always check the soil before watering.

If foliage starts to turn yellow and growth is also stunted, check the pH and amend with an acidifier as necessary.

Burpee Azalea, Camellia, Rhododendron Plant Food

Feed during the growing and flowering season with a fertilizer for acid-loving plants, such as Burpee Natural Organic Azalea, Camellia, Rhododendron Plant Food, available from Burpee.

Follow the package directions for plants grown in containers.

Pruning

Winter daphne doesn’t require much if any pruning. Its branches don’t heal well from cuts, so it’s best to put up with any straggly-looking growth until the plant reaches its adult height.

Prune only after flowering. Even then, it’s best to only remove dead or damaged wood, cutting about a quarter of an inch back into healthy wood.

Snipping flowers on stems to have on display in the house is often enough to maintain shrubs. These will last up to a week in water and fill the house with their sweet scent.

Cultivars to Select

D. odora comes in a range of flower colors from pure white to deepest maroon. Variegated cultivars provide flashes of gold-tinged foliage throughout the year.

Here are a few recommendations to whet your appetite:

Alba

Masses of snowy white clusters are set against deep green leaves.

‘Alba’ has a lemon scent that’s said by some to be the most pungent of all varieties and grows three to four feet high, with a spread two to four feet wide.

Aureomarginata

Also known as ‘Marginata,’ ‘Aureo’ means gold, and this beautiful cultivar’s deep green leaves are edged in a line of bright yellow.

The starry flowers are a blend of white to pale maroon-pink. It grows three to four feet high with an equal spread.

Maejima

This striking plant has flowers with a delicate white pink inside and maroon-purple on the outside.

However, it’s a bright, bold presence year-round thanks to the thick yellow border on its green leaves. It grows three to five feet tall with the same spread.

Marianni

Also known as ‘Rogbret,’ the flowers are a beautiful pale pink, edged in a richer plum-pink tone. ‘Marianni’ grows three to five feet tall and wide.

‘Marianni’

Order one-and-a-half- to two-year-old ‘Marianni’ plants from Nature Hills Nursery.

Perfume Princess

This hybrid cultivar is a cross of D. odora and D. bholua, also known as Nepalese paper plant.

The result is a pungent winter daphne with blooms four times larger than those of D. odora, closer to the size of D. bholua blooms at around four inches across, with the bonus of extra flowers along the stems on mature plants.

It flowers earlier and for a longer period than D. odora as well.

Shoutout to its breeder, my countryman and legendary plant breeder Mark Jury of New Zealand, who spent more than a decade working to create this variety.

There are two types, one with pale pink flowers, the other pure white. Both grow to around three feet high by three feet wide.

Rebecca

Rose-purple buds open to gorgeous pale lavender-pink flowers.

‘Rebecca’ is similar in appearance to ‘Aureomarginata’ with a band of yellow around the edges of the foliage, and grows three to five feet high by three to five feet wide.

Zuiko Nishiki

A Japanese cultivar with fragrant white flowers with pink edges, ‘Zuiko Nishiki’ is said to be more cold-hardy than other varieties of D. odora.

This cultivar grows three to four feet high and three to four feet wide.

Managing Pests and Disease

Horticulturalist Dr. Michael Dirr has some strong thoughts on daphnes.

He’s considered one of the foremost experts on woody plants in the US, a professor of horticulture at the University of Georgia, and a long-time author with many published books, including “Dirr’s Encyclopedia of Trees and Shrubs,” which is available from Amazon.

Dirr’s Encyclopedia of Trees and Shrubs

“Many die for no explicable reason. It has been my pleasure to lose more than I can count on fingers and toes, but I continue to plant.”

Read more about possible reasons and what may, or may not, prevent it in the Sudden Death section below.

Pests

Plants are most often affected by insect pests when conditions are poor, such as too much or not enough water, a nutrient deficiency, or getting too cold over winter.

Scale insects look like tiny black or brown barnacles on the leaves and stems. Check out our article on how to identify and control these insects for more information.

Winter daphne may also be affected by aphids. Read more on how to control and eradicate aphids in our guide.

Mealybugs can also infest these plants. You can learn more about mealybugs in our article.

Diseases

D. odora doesn’t tend to survive longer than about five to eight years, and usually dies due to disease.

In other parts of the world they may grow for 10 to 15 years in cultivation. Experts surmise this may be due to some regions not having certain types of fungi or bacteria that may infect the roots.

Leaf Spot

Brown spots on foliage can be caused by fungal or bacterial leaf spot. Remove affected leaves and treat with a copper-based fungicide.

Root Rot

If soil conditions are too wet, winter daphne is prone to suffering from root rot caused by Phytophthora water molds.

Read more in our guide on How to Manage Root Rot in Fruit, Nut, and Landscape Trees and Shrubs.

However, rotting roots can also be due to a fungal infection.

Sudden Death

Daphne species are so renowned for dying suddenly without warning, within days, that there’s a name for it: daphne sudden death syndrome.

Also known as sudden daphne death syndrome, or SDDS, one of the first signs of a plant’s decline is yellowing leaves. These can first appear due to cultivation issues, such as:

- Under-watering

- Overwatering

- Soil pH too acidic

- Soil pH too alkaline

- Poor soil drainage

- Lack of available nutrients such as iron

It’s possible to correct these issues and hopefully save your plant, but often the culprit is a fungus that’s naturally present in your garden’s soil, which takes advantage of the plant’s weakened state as it ages and suffers environmental stress.

Research has found a fungus called Thielaviopsis basicola is responsible, but there may be different species of fungi worldwide that cause it.

The plant’s crown and roots develop brown to black lesions. Leaves start turning yellow, eventually falling off. Once this starts happening, the plant dies within 14 to 21 days. There’s no cure.

While you’re likely to see infections due to management issues like those outlined above, sudden death can also just happen with no clear cause, even to a plant in an ideal situation.

The experts agree it’s best to accept D. odora is only going to be around for a short time, and to propagate or buy replacements before its inevitable decline.

Don’t plant another one in the same place, or close to where one has died, in case pathogens may be present.

Best Uses

The best position for it is close to the house, under a kitchen window, near a walkway, or in a pot on a patio or deck, so you don’t miss the masses of flowers and their stunning fragrance on cold spring mornings.

Plants can also be grown together, to form a hedge.

Cut flowers last for about a week in water and will continue to give off their beautiful scent.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Flowering evergreen shrub | Flower / Foliage Color: | Pink, red, rose, white / green, variegated |

| Native to: | China, Japan | Maintenance: | Low |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 7-9 | Tolerance: | Drought |

| Bloom Time: | Spring | Soil Type: | Sandy loam |

| Exposure: | Morning sun, dappled shade | Soil pH: | 5.5-7.0 |

| Time to Maturity: | 1-2 years | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | 2-4 feet, depending on variety | Attracts: | Bees, butterflies, moths, flies |

| Planting Depth: | Same depth as its original container (transplants) | Companion Planting: | Grape hyacinth, clematis, coral bells, geraniums, Hakone grass, sedges, low-growing thyme |

| Growth Rate: | Moderate to fast | Order: | Malvales |

| Height: | 3-6 feet, depending on variety | Family: | Thymelaeaceae |

| Spread: | 2-4 feet, depending on variety | Subfamily: | Thymelaeoideae |

| Water Needs: | Low | Genus: | Daphne |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Aphids, scale; leaf spot, root rot, sudden daphne death syndrome | Species: | Odora |

Don’t Be Without a Daphne

Dr Michael Dirr proclaims “a southern landscape without fragrant daphne is really not a garden.”

In the middle of spring in my part of the world, I’m in complete agreement despite the winter daphne in my garden starting to look a little miserable with some leaves yellowing.

I suspect a wet winter and weeks of tradespeople stomping on the soil in its corner of the garden as they fixed rotten weatherboards might be to blame.

Yet, its sweet scent is wafting in through the bedroom windows, and I’ve already decided where I’ll plant the next ones.

Do you grow D. odora? How have you found it? Let us know in the comments below.

And for more fragrant flowering options to add to your garden, read these guides next: