[ad_1]

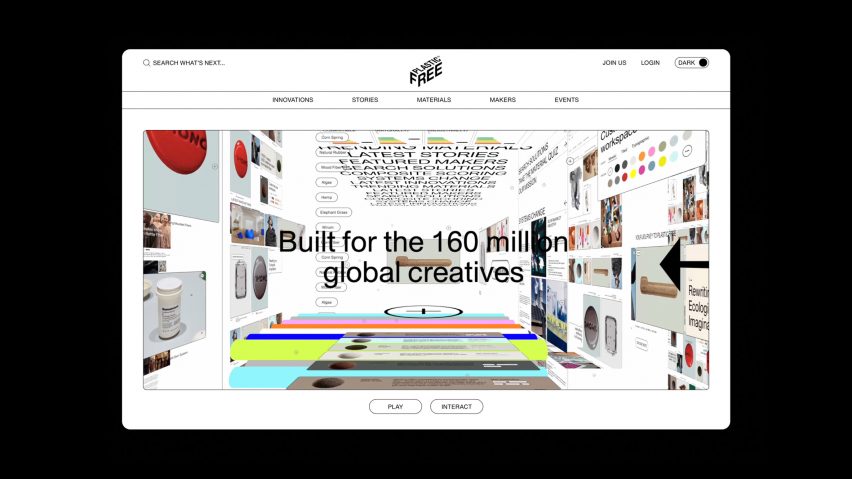

Environmental charity A Plastic Planet has launched an online platform to help architects and designers source plastic-free materials for their projects and avoid the “minefield of misinformation” around more sustainable alternatives.

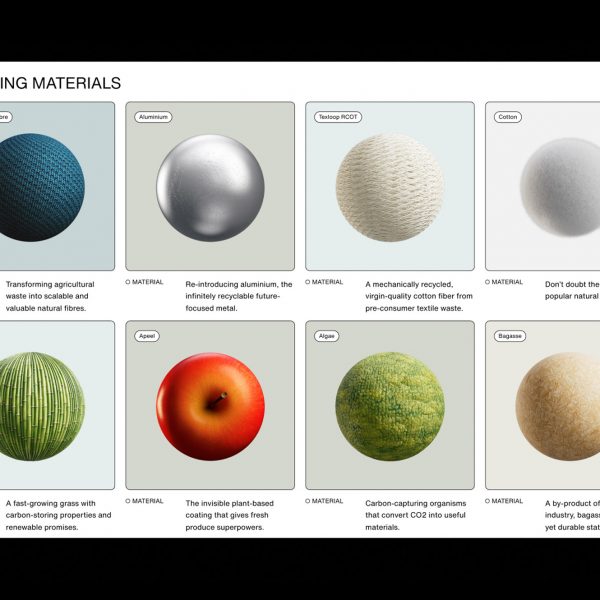

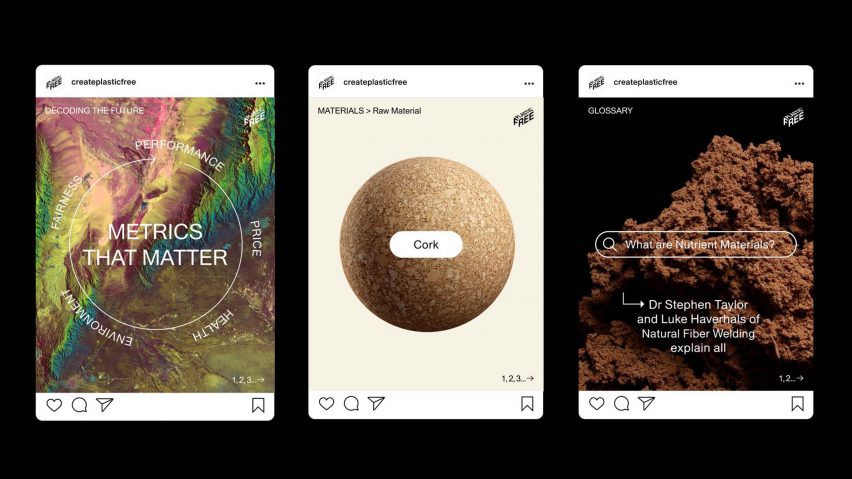

Called PlasticFree, the subscription-based service provides users with in-depth reports on more than 100 plastic alternatives, offering key insights into their properties, production and sourcing.

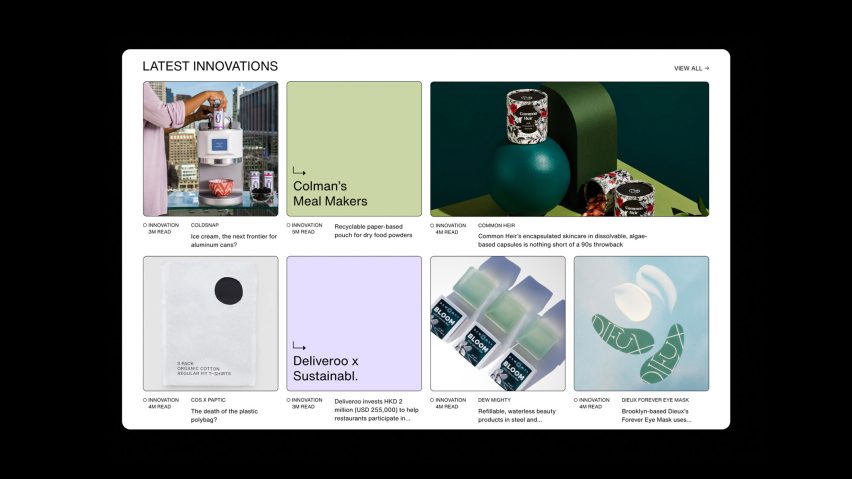

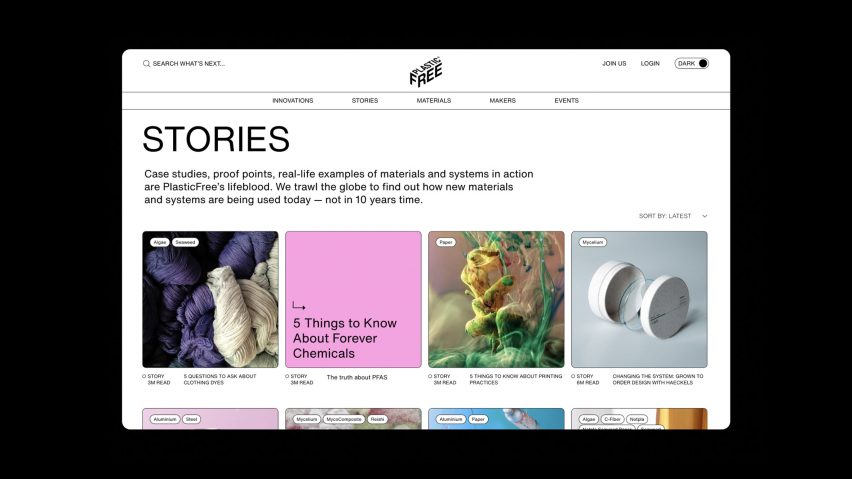

Part material library, part design tool, the platform also highlights case studies on how these materials are already being turned into products across five different continents and allows users to collate them into Pinterest-style mood boards for their projects.

The ultimate aim, according to A Plastic Planet, is to “help designers and business leaders eradicate one trillion pieces of plastic waste from the global economy by 2025”.

“No designer on the planet wants to make branded trash,” the charity’s co-founder Sian Sutherland told Dezeen. “They did not go to design school and care about everything that they produce every single day for it to end up in a bin.”

“But I don’t think designers have been trained for what is expected of them today,” she added. “So we wanted to create an absolutely authoritative, unbiased, material-agnostic platform that designers can use to learn about materials and their systems.”

PlasticFree is the result of more than two years of research and development in collaboration with a 40-strong council of scientists, business leaders and industry figureheads including Stirling Prize-winner David Chipperfield, designer Tom Dixon and curator Aric Chen.

In a bid to offer a reliable, trustworthy source of information, each material was carefully vetted by an “army” of scientific advisors based on an extensive data collection form and A Plastic Planet’s Plastic Free Standard, Sutherland explained.

“Designers want to be part of the solution but there is a minefield of misinformation out there,” she said. “It’s taken us two years to do all the research on these materials, to drill down and ask all the questions so that our audience doesn’t need to ask them.”

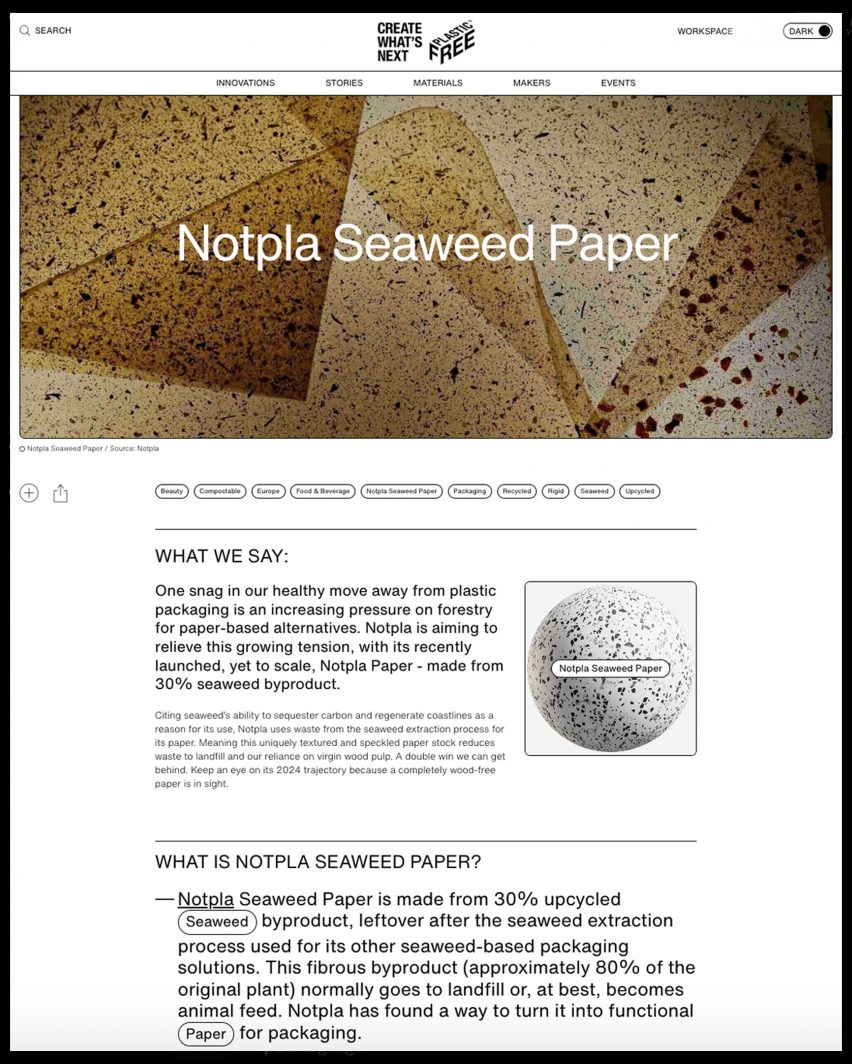

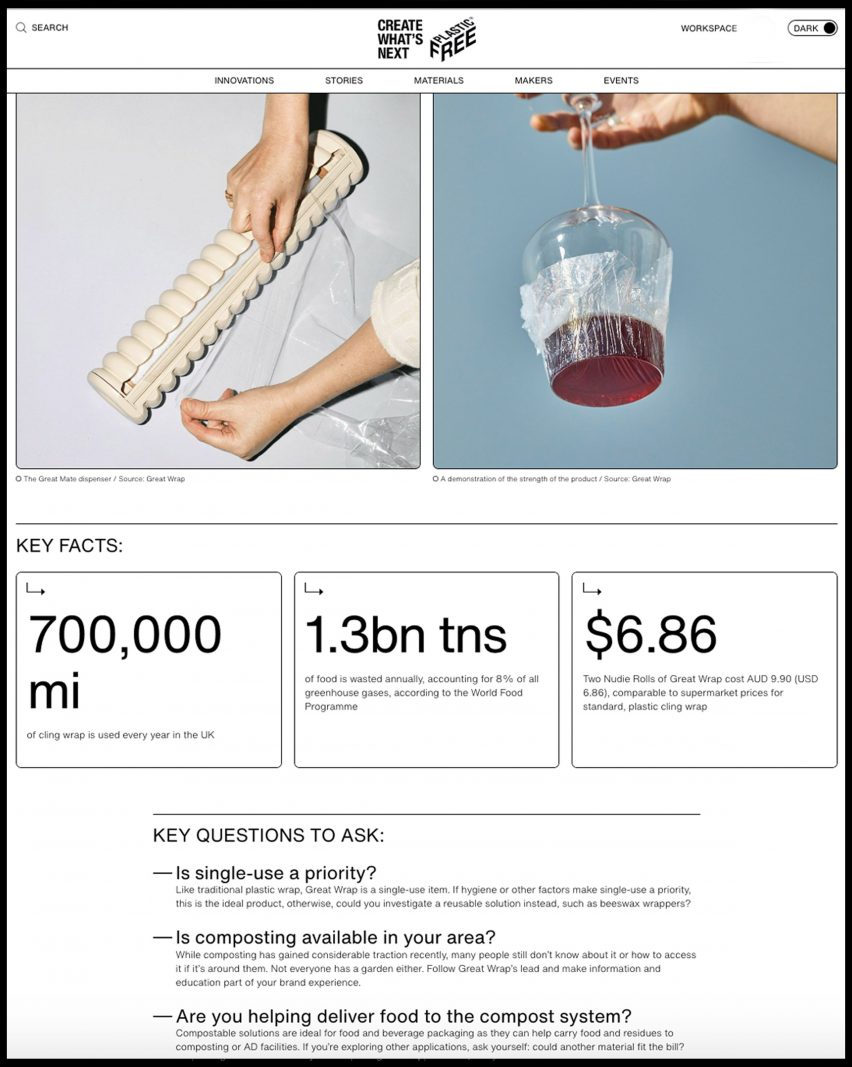

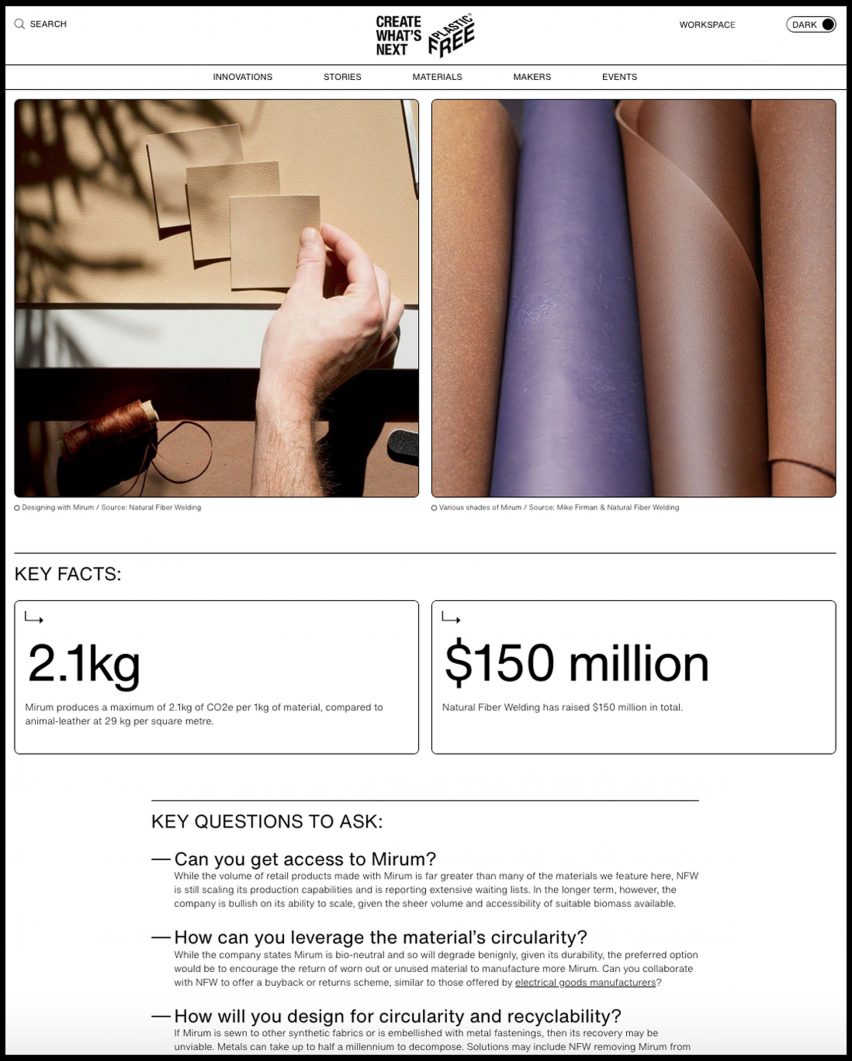

All this information is condensed into a report, summarising each material’s key traits, its stage of development and sustainable credentials such as water savings.

Each profile also includes a list of key questions that designers will have to consider if they want to work with the material, such as whether it will be on the market in time or whether it needs to be integrated into a reusable product to offer emissions reductions.

“It’s about how we can empower designers by telling them what questions they should ask of a materials manufacturer,” Sutherland said.

“How can you push back against that brief that says: just use a recycled polymer or a bioplastic? How can you challenge a lifecycle analysis? Because I sit on those calls and I hear the complete bullshit that is spewed out all the time.”

PlasticFree’s database, which will be constantly updated, focuses on the sectors that currently use the most plastic – namely packaging and textiles, with buildings and construction set to be added later this year.

It features raw materials such as bamboo and cork, alongside more specific innovations such as Great Wrap’s potato-based cling film and Living Ink’s algae ink.

Some of these materials – like bioplastics and recycled plastics – are merely “transitional” and, according to Sutherland, represent “a foot on a better path” rather than a viable solution to plastic pollution.

The real promise, she argues, lies in fossil-free “nutrient-based” materials such as Notpla’s edible seaweed packaging or Mirum plant leather, which are able to go back to the earth as nutrients.

“That is going to be the future of materials,” Sutherland said, “for everything from the houses we live in and the fabric we wear, to the products we buy and the packaging in which they’re sold.”

PlaticFree’s Stories section also houses more educational content on everything from clothing dyes to the “forever chemicals” in our plastics, in the hopes of pushing the wider systems-level changes that need to go along with this material transition.

“Above all, our focus is on system change, not just better materials,” Sutherland said.

“How can we have permanent packaging? How can we make things that are durable, that feel beautiful in your hand, that make you feel even fonder of them as they age? How can we get off this ever-moving conveyor belt of new?”

Sutherland founded A Plastic Planet together with Frederikke Magnussen in 2017, with the aim of inspiring the world to “turn off the plastic tap”.

Since then, the charity has rallied both industry and policymakers behind its cause, creating the “world’s first” plastic-free supermarket aisle as well as working with the UN to realise a historic global treaty to end plastic waste.

[ad_2]

Source link