[ad_1]

When I arrived at the Biophilic Leadership Summit in Georgia’s Serenbe community in late April, I fully expected to be thrown into the deep end of academic and professional discussions dedicated to a concept striving to evolve into a worldwide movement. The roster of researchers and practitioners spanning fields from architecture, landscape design, horticulture, education, urban planning, governance, and the neurosciences promised big ideas in response to the enormous challenges existing between housing, health, and the environment. Some were there to divulge ongoing research, others to promote practices, and some even to rally debate about the core tenets of biophilic design.

Serenbe’s Selborne hamlet.\ Photo: Serenbe

Serenbe’s planners can certainly see the forest for the trees – and vice versa. The verdant expanse of Chattahoochee Hill Country in Georgia located about 40 minutes outside of Atlanta is now home for over 800 residents and ever growing. \ Photo: Serenbe

Oft connected to the work of social ecologist Stephen Kellert and Edward O. Wilson’s seminal 1984 biological hypothetical Biophilia, practitioners of biophilic design endeavor to reorient the built environment into holistic experiences beyond donning the veneer of nature. In simplest terms, biophiliacs believe we’ve evolved as a species to be our happiest, healthiest, and most productive surrounded by nature, so why not design our communities to tap into that deep seeded wellspring of good vibes?

The multi-day conference focused upon the theme of “Emerging Concepts in Biophilia.” “Nature & Neuroaesthetics” with Anjan Chatterjee, M.D. in Conversation with Jennifer Walsh kicked off the first of many presentations.

Serenbe co-founder, Steve Nygren

With obvious intent, the strongest case for biophilic design as a realizable goal is the site of the summit itself. Founded by Steve Nygren and Marie Lupo Nygren in 2004, Serenbe exists both as a developing proposition and an established example of biophilic design put into action. It’s also a residential concept that isn’t really new at all.

Biophilic Leadership Summit speakers such as Bill Browning of Terrapin Bright Green (above), architect Tuwanda Green, Professor of Architecture Phillip James Tabb, and Professor of Neurology, Psychology, and Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania Anjan Chatterjee were amongst experts in attendance discussing biophilic design from various perspectives. Author and former Senior Partner and Global Managing Director for design firm IDEO Fred Dust presenting the keynote.

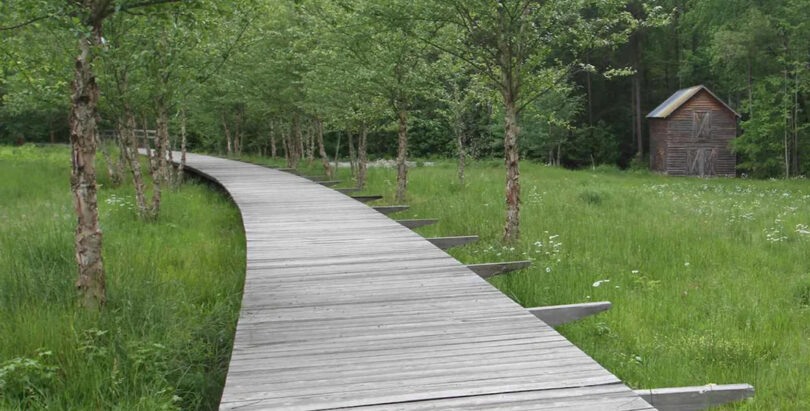

Comprising an interconnected network of homes, small businesses, parks, community centers, and even a working farm, the sum of Serenbe evokes a nostalgic and idyllic remembrance of small English countryside townships, complete with hallmarks of agrarian structures interspersed alongside modern architecture worthy of a Dwell feature (and in fact, a few homes have been featured as noteworthy architecture across numerous outlets).

The forest is ever present, with creeks and footpaths winnowing between homes, the sounds and scents of the natural world just as much a neighbor as the residents themselves.

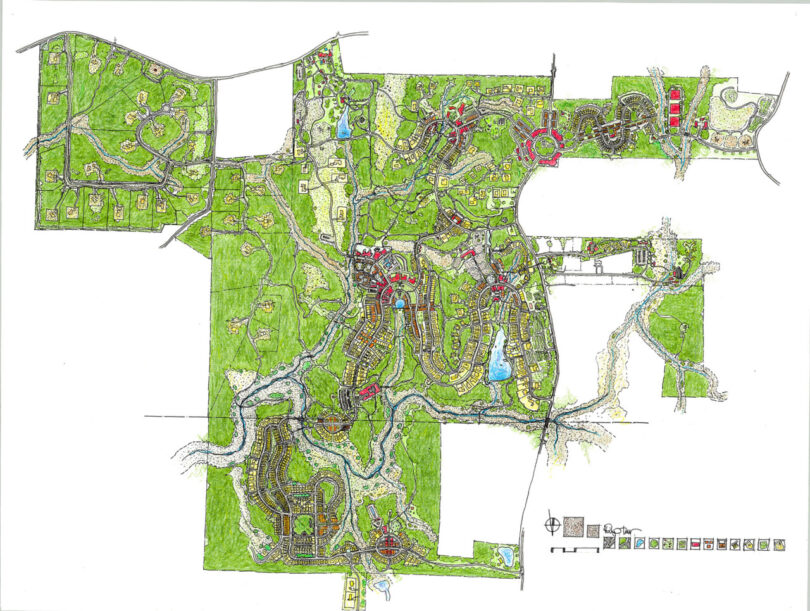

Serenbe is shaped by twelve biophilic principles, each intended to influence planning and design in service of four goals: community engagement, national security, global balance, and personal wellbeing.

Nygren says Serenbe’s imprint upon the landscape is always intended to be minimal, abiding by a 70/30 ratio no matter how much land is eventually appropriated into its limits, with 70% of total land protected from development, the remaining 30% developed with minimal intrusion. The resulting neighborhood(s) invite walking, biking, and unplanned socializing as natural outcomes of a plan deemphasizing the car (automobiles are visible aplenty, possibly more a charge against American lifestyle than city planning).

Exploring Serenbe by foot, its hard not to consider the trees as much part of the citizenry as the residents themselves, an orchestrated sensation conjured by its 16 miles of nature trails principles and the integration of “sacred geometry” – shapes found in the reoccurring patterns and ratios within nature (think: Fibonacci Spiral) – prevalent in every small and large detail strewn throughout the town’s limits.

2021 Atlanta Homes & Lifestyles Serenbe Designer Showhouse, built by South Haven with Landscape Design by Floralis

The Naturally House in the Serenbe hamlet of Mado was architecturally inspired by a treehouse.

Architecture in Serenbe ranges from traditional, historic, mid-century to contemporary. Buyers can purchase plots of land and hire their choice in architects if desired (requiring they meet certain sustainable design qualifications).

Nygren makes special effort to point out while Serenbe is suburban in plan, its was conceived from the start to invite a level of density no longer permitted in most new community developments. “See that large house there?” asks Nygren, stopping to point toward a residence during a tour. “Across the street we’ve built several houses closely together. And over there are apartments and businesses. That sort of multi-residence isn’t allowed elsewhere because of zoning laws.”

Larger plots measured in acreage are available to develop, but just as numerous are slim multi-storied condos and smaller homes. Senior residential housing is available, inviting an inter-generational populace; Nygren’s grandson scurried happily across a park to greet him along the tour. In certain sections of Serenbe this density imparts the community with an old European city vibe, complete with bridges and narrow cobblestone paths. The only tells being the general emptiness of many sections of the community, alongside an occasionally artificial veneer of age (this can sometimes give Serenbe the semblance of a beautiful movie set still waiting for cast and crew to arrive).

Map by Phi

But the most visible imbalance in Serenbe is its lack of socio-economic-racial diversity, something Nygren acknowledges in passing before emphasizing the availability of affordable housing and rental options as a developing antidote for sprawl.

Beyond Serenbe’s architectural diversity and communal planning, it is the blurred transition between Serenbe’s residential plots and the surrounding natural landscape that proves quietly satisfying for residents and visitors alike. Everywhere shaded stairs and walkways needle between homes, allow walking as an inviting option. Viridescent canopies of trees and the understory untouched by landscaping are a constant presence, with curving sight lines rather than stringent grids defining the community. This hazy and meandering intersection of personal and communal space results in a gradient rather than the harshly demarcated lines typical of modern American suburban living.

Serenbe’s tapestry of green spaces are communal threads intentionally positioned to tighten the bonds of its residents across specific neighborhoods (“hamlets” in Serenbe parlance), independent businesses, and communal spaces.

What began as a 60-acre farm purchased by the Nygrens in 1991 as an escape from the urban life rather than a permanent address has slowly evolved into a convincing argument housing should be developed with considerable thought beyond all the selling points currently defining real estate. Biophilic design can be the foundation, roof, and walls to a better life. For better or worse, Serenbe may be the closest realization to a suburban utopia imagined through the lens of American society ever realized. In fact, its success has gone on to garner attention and inspire new developments of environmentally-focused, integrated walkable communities, with more to come.

Artist and photographer Thomas Jackson tulle and plastic cup installations inhabit secret corners of Serenbe’s forests.

A sense of surprise permeates every section of Serenbe, including public art strewn in easily accessible and within hidden pockets of its forested border, something that elicited joy throughout our tour and my own exploration of the community. A memorable example was found behind Serenbe’s Blue Eyed Daisy Bakeshop, the smallest Silver LEED-certified building in the nation. Just around its corner, an intimate courtyard hosts a chalkboard wall covered in friendly messages left by visitors and residents alike. A quarter turn of the heel to the left and a dappled shaded path hints views of shaded woodlands – tempting awe rather than fear. Getting lost and eventually finding your way in Serenbe seems to be essential to the experience.

[ad_2]

Source link