[ad_1]

More City than Water: A Houston Flood Atlas | Edited by Lacy M. Johnson and Cheryl Beckett | University of Texas Press | $39.95

The water is rising along America’s coasts. Places like New Orleans, Naples, Siesta Key, and Captiva Island (where Robert Rauschenberg worked) all have flood stories to tell. How long will it take before all littoral cities will forge atlases of inundations?

For Houston, a city separated from the coast and not properly “coastal,” the topics of concern in the national conversation are either “energy markets” or “no zoning.” Ocean rise does not come to mind—Houston is 50 feet above it all! But since it is linked by a long waterway and a delta of bayous that unite in frequent deluges—alternately the result of intensive rainfall or surges up from the Gulf of Mexico—waters have and will come. The bayous have been expertly reconfigured and buried; they now serve as paved runoffs. In addition, the wealthier parts of the large agglomerations are hidden under a zoohemic tree canopy, which covers the wet prairie. Yet almost as a surprise, hurricanes sweep water across the expanse, which invites the actual intentions of More City than Water: A Houston Flood Atlas. When those monsters rage, the city’s inhabitants rise above.

Editor Lacy M. Johnson—writer, associate professor of creative writing at Rice University, and founder of the Houston Flood Museum—reminds us that Houston is not all tranquil subdivisions, crowded baseball diamonds, and frenetic oil derricks, tucked under a “faux-forested” canopy. It is also wet. Too often and too dramatically, too many wade waist-high in a “rank contagion of human and industrial waste,” she writes.

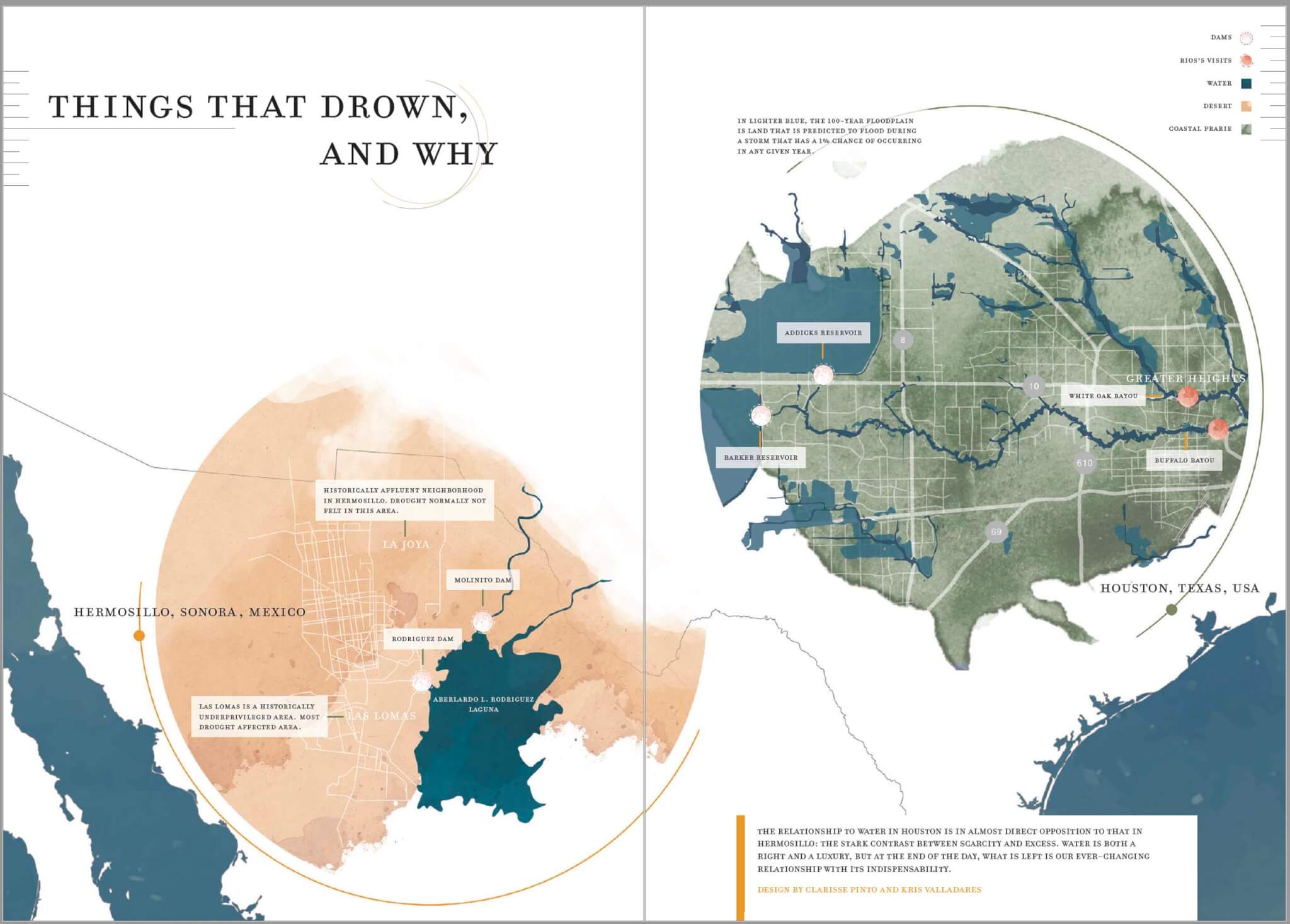

Johnson created the Houston Flood Museum after Hurricane Harvey in 2017. Its online collection about the storm showcases the state just before the physical city is projected to disappear. Twelve graphic maps, illustrated in watercolor-like washes and edited by the coauthor Cheryl Beckett and a staff of graphic artists, run side by side with the chapters. Beckett’s core team of three illustrators—Ilse Harrison, Jesse Reyes, and Manuel Vázquez—is in turn supported by almost 20 map designers. The maps are inventive, often beautiful, and contribute to the poetics of the whole project. They possess the contradictory fusion of graphic beauty and actual terror, a reminder that when humans experience disasters there can be positive consequences and hope.

As expected, the atlas is full of Houstonians. Essay contributors, activists, poets, and fiction writers include author Bryan Washington, environmental anthropologist Dominic Boyer, and climate anthropologist Cymene Howe, with the essays grouped under the themes of history, memory, and culture. Within the atlas’s pages, we are on dry land. In Washington’s text, the high ground is the ultimate resort of a flooding city, which sends folks back to bed. That is until a hurricane climbs the bed legs. Houstonians do prepare for storms, but it’s the generic storm we have in mind, not this one, the storm that is mine or, as in Washington’s case, his family’s. The question remains: How long will we have to rely on the fickle high ground as a pacifier? Especially since the sky is the limit.

The section on community is broad, deep, and multidimensional—the word alluvial comes to mind. Ben Hirsch, codirector of organizing, research, and development for the Harvey relief organization West Street Recovery, speaks of community power, listening, and responding, what my old sociology professor instilled in me: When in doubt, go out and look. Boyer’s powerful depiction of “A Whole City on Stilts” communicates how the sound of water lapping inside the house is never forgotten. Community complaints of “too little, too late” join hydraulic jacks and flood insurance, leading Boyer to lose faith in stilts and conclude, “I wonder whether Houston might eventually become the first ghost megacity.”

Seen by developers as a flat plane, despite a rolling topography, three distinct ecologies, and 22 bayous, Houston houses some six million inhabitants and counting. It is obvious that despite floods, Houstonians love their city. Although we have all lived through the same floods, we are separated by certain distances—social and economic, lateral and vertical. The idea that each flood is my flood is clear in the 18 essays: The writer is the subject, and the offerings become a set of first-person narratives. Memories are tricky: Do I remember the event, or how I felt with the water rising, or is it an elaborate reconstruction? Is my story in focus, or the water’s? The stories are personal—Johnson herself shines as a memoirist—and show how the flood entered each life story. “The living water” of Johnson’s memory invades and settles, becoming part of our existence and adding complexity. Johnson writes that “flooding reinforces the inequalities that surround us every day” and further accentuates how intimate and familial floods are, while simultaneously reinforcing the social striations seen in the city’s population. Could the experiences of flooding create a new community with political power? Such opportunities fade when Houston dries and returns to complacently boasting about being the most diverse city in the country.

In too many houses during too many storms, too many families watched the waters rise. The murk swallowed walls, minute by minute, destroying with varying effect everything in its rise. Captured in photographs, these views sit frozen and museum-like, while in motion, the observer drowns too. The common sense of sinking must be the source of the instant community that Johnson and many of the writers often refer to. Here, images of hell are interspersed with kindness: We see a young man guiding a floating inner tube carrying an elderly person and a cat. Suddenly everything is on the move. We see a house afloat or tilting radically, drifting across a flooded plain. Eighteen-wheelers majestically afloat on their side in a sunken freeway, drivers missing. Kibitzers on the bridge above look dazed, transfixed, staring. Everything has become unmoored.

There is a synthetic, all-inclusive quality to the atlas’s entries. Its disciplinary origin is worth highlighting: The atlas is largely charted by members of language faculties, not environmental engineers, and this shapes the remedies. For example, the atlas offers no solutions, such as filling the low-lying large “hog hollows” that poor people live in without flood protection. Instead, it documents “a story of sacrifice and resilience, of working together for the common good.” In the face of a hurricane that drops 60 inches of rain, a curious transformation takes place. In normally physically and socially separated populations, hardy communities bloom, revealing a dormant public just waiting to excel under duress.

There are surely ways to redesign the city that can that can help reduce flooding. City governments know this, but economic interest mixed with politics gets in the way. Communities of resilience are painfully aware of this, so the atlas shows us where spontaneous democracy appears behind the official facade, floating in rubber boats, grand trucks, kayaks, and inner tubes. Meanwhile those of us who live several feet above, and many yards away, are watching the drama on television. To view hurricanes as an oft-repeated, yearly phenomenon makes climatic sense and must be elected officials’ position. But rather than a unified response, each experience is individual, just like each hurricane is personified. The issue isn’t really a technological one. As Daniel Peña writes, “This is a socioeconomic/race/ class problem, not a climate change problem,” a necessary declaration for those concerned with climate change. Portrayed by media as a “disaster-porn-freak-show,” storms are entered as “evidence” by those who accept climate change, rather than devastating occurrences, and for those who deny it, Peña suggests it’s merely a TV show with no lasting effect. His James Baldwin–inspired text shows how painful and multipronged climate disasters are. The failures behind are not just climactic but embarrassingly human, exposing our centuries-long hubristic relation to nature.

Johnson’s interviews are effective. She speaks with Grace Tee Lewis about air pollution and with editor Raj Mankad, who argues that “Houston is in denial of its history of flooding.” The reason has a lot to do with the fact that it is an ever-expanding city with no time for reflection. Since inundation is part of the workings of a delta and mostly affects those with less power, it is kept in the background.

Today, the building of low-income housing in the outdated floodplains continues. As insurance companies get real about the climate crisis, flood insurance, one of those much-loved instruments that for years has given free rein to developers, comes into focus. How many times can you rebuild a flooded house? Well, it depends. Particularly for those who now live in areas that repeatedly flood. The answer should be that developers cannot build where flood insurance cannot be obtained, but such simple solutions are politically impossible. Somehow strangely imbedded in the thirsty real estate enthusiasm is a Houston whose magnificent bayous and ecologies endure, if you know where to look.

A next volume of the atlas may need to chart how folks accommodate the evolving climate and make room for water. Already, some communities have no legitimate hope for change. In that case, the adjective resilient lands as a pejorative rather than a compliment. Still, Houston’s future may “go Dutch” via construction dikes, barriers, boosted by pumps: Last year, the federal government approved the start of work on the Ike Dike, a massive, $31 billion effort planned to regulate Galveston Bay through large gates at its opening to the Gulf of Mexico. Here, public works à la Rotterdam and its Maeslantkering will be built, supposedly protecting residents and, importantly, the working bits of much of the country’s oil economy, lodged along the perimeter of the Ship Channel. Two contrary worlds are in the making: a water-tolerant Houston that survives and a laissez-faire Houston that disappears.

One thing the atlas confirms is that flooded Houstonians, when facing the inevitable next storm, will again gather to make good on their alliances. Never failing their orientation, the band of Houstonians featured in this book eloquently prove the power of the pen by offering a realistic climate poetics. If persistently and repeatedly applied to densely inhabited flood zones, atlases like this one may lead to a global wake-up call whose alarm may even reach the politicians.

Lars Lerup is a Houston writer whose latest book, The Life and Death of Objects: Autobiography of a Design Project, was published in 2022. When the Center No Longer Holds, a book on motorized urbanization, is in the making.

[ad_2]

Source link