Eriobotrya japonica

For a beautiful evergreen tree that produces amazing flowers and delicious fruits, have you ever considered loquats?

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

If you’re like me and consider yourself a seasoned connoisseur of fruit, fruit-laden energy bars, and the like, you may be a tad bit bored with the staples.

If bananas, apples, and oranges aren’t really doing it for you anymore, then consider the loquat: a unique, yummy pome fruit that’s tough to find in commercial markets, but well worth procuring.

Delicate to handle and quick to spoil, loquats are proof that the brightest fires tend to burn out the quickest.

If you want to have loquats on hand for munching, your best option may be to grow them yourself. But if you need more than fruit to justify its cultivation, the tree is quite the aesthetic specimen as well.

In this guide, we’ll cover the ins and outs of Eriobotrya japonica. By its end, you’ll have all the know-how necessary to grow beautiful and scrumptious loquats in your garden.

What Are Loquat Trees?

Native to China and hardy in USDA Zones 8 to 10, Eriobotrya japonica is a gorgeous evergreen fruit tree that can grow 10 to 25 feet tall and wide.

The tree is a member of the Rosaceae – aka the rose family – alongside pears, apples, and quince.

This bushy, dense tree does well in USDA Hardiness Zones 8 to 10. It can survive temperatures as low as 10°F, but freezes below 27°F can kill the flowers and fruit.

As prized for its beauty as it is for its tasty offerings, loquat flowers in the fall to early winter and produces fruit in late winter to early spring. The tree is also pretty vigorous, with the potential to grow three feet in height per year in optimal conditions.

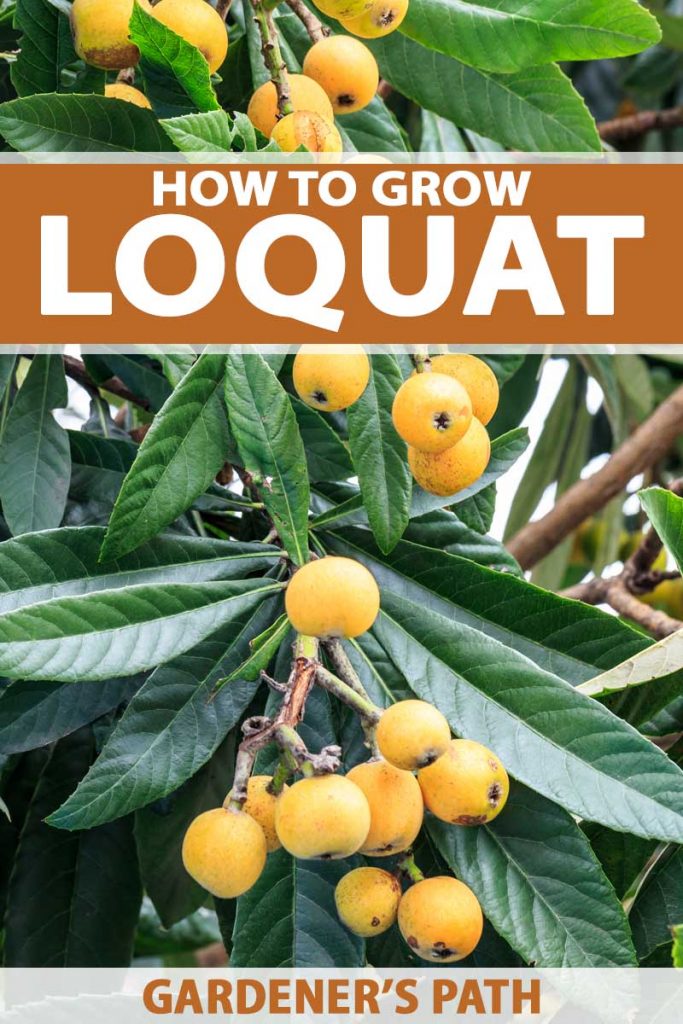

Loquats bloom with clusters of small, delicate, white flowers that produce a sweet fragrance that carries for long distances. Later, the pollinated flowers give way to round or pear-shaped yellow to orange fruits, which are about one to two inches in length.

Ripening in spring, the yellow, orange, or white flesh of the fruit is sweet and slightly acidic. This sweet-tart flavor has been described as being similar to that of a plum, lemon, apricot, cherry, grape, or some combination thereof.

The fruit is delicious when preserved in jellies or jams, used in recipes, or even eaten plain.

Full of vitamins, minerals, and dietary fiber, the flesh of the fruit has a soft, almost apple-like texture to it. “An exemplary mouthfeel,” a sophisticated food critic might say.

Within these fruits lie two or three large brown seeds, which contain cyanogenic glycosides that are mildly poisonous to humans.

If consumed in large amounts, these may cause weakness, vomiting, labored breathing, twitching, convulsions, and stupor. Remove the seeds before eating or cooking with the fruits.

Capable of reaching a foot in length, the tree’s evergreen leaves are shaped like narrow, pointed ovals, with coarsely-serrated margins and a dark green hue. Younger leaves are downy, whereas older leaves become more leathery.

Equally attractive is the tree’s coarse and partially exfoliating bark, which is gray on the surface and brown beneath.

Cultivation and History

The history of loquats starts in their native home of southeastern and central China, where they have been cultivated for over two millennia.

The plants were first brought to Japan over 1,000 years ago and have been grown there ever since, earning E. japonica the common nicknames “Japanese plum” and “Japanese medlar.”

Loquat leaves were used in traditional Chinese medicine as a treatment for chronic bronchitis.

The foliage is also used in tea – called biwa cha in Japanese – and used as a diuretic aid, digestive agent, and fever reducer in traditional Japanese medicine.

Biwa cha is still consumed as a health drink in Japan today, as it contains high levels of antioxidants and shows anti-inflammatory activity.

But back to the past: in commerce with China, traders from the Philippines acquired loquat specimens of their own.

After the Spanish took over the islands, claiming them as a part of the Spanish East Indies, they would eventually disseminate E. japonica specimens from the capital city of Manila via galleon ships to their New World port in Acapulco, Mexico.

Others in the Old World first gained official botanical awareness of the loquat in 1690, when Engelbert Kaempfer, a botanist for the Dutch East India Company, first described and named the tree.

He took the genus name from the Greek erion and botrys, meaning “wool” and “bunch of grapes,” a reference to the somewhat wooly and grape-like fruit clusters.

Since the trees were so well-naturalized in Japan, Kaempfer erroneously assumed their Japanese nativity, assigning the trees the specific epithet japonica.

In the late 1700s, loquats were planted in France’s National Gardens and England’s Royal Botanical Garden.

Gardeners from other regions of Europe such as the Mediterranean, as well as North Africa, South America, Australia, New Zealand, and the southeastern United States started to plant E. japonica throughout the 19th century.

To this day, the loquat has remained a beautiful and delicious choice among subtropical gardeners the world over. You can even plant this tree in a container and grow it as a houseplant.

Propagation

To acquire an E. japonica tree of your own, the best way is to transplant a grafted or budded specimen. For ideal fruit production, you’ll want to plant more than one.

Sexual reproduction is unpredictable, often frustratingly so. Especially in fruit trees, as growing one from a seed rather than a graft will almost definitely leave you with a plant that’s not true to its parent. Meaning: you might not end up with the exact fruit that you intended.

Plus, you’ll have to wait about a decade before you can harvest a super ample crop from a seed-grown tree. A grafted or budded specimen, on the other hand, should begin bearing the exact fruit you intended once it’s three to five years old.

“But what about cutting propagation?” While it will provide an exact clone of a parent, rooting an E. japonica cutting is no easy feat.

Plus, a cutting-grown plant is still slower to yield fruit than a properly grafted or budded specimen… and given a loquat’s average lifespan of 20 to 30 years, time is precious.

Grafting is a process wherein you combine the upper fruit-bearing part, or scion, of one plant with the lower part and root system, or rootstock, of another.

Budding is similar, except the scion is an actual bud instead of woody tissue. If the union is successful, you’ll end up with traits from both the scion and the rootstock in the same specimen!

Grafting and budding techniques are pretty involved, and thus beyond the scope of this article.

To buy a grafted or budded specimen, plant nurseries are your best bet. They’re quite seasoned in grafting and budding, and you’ll save yourself a fair amount of time by purchasing from them.

The best time to transplant a specimen is in early spring, after your area’s average last frost date.

At this time, prepare well-draining planting sites with a soil pH of 6.0 to 7.0, situated in full sun and spaced at least as far apart as you’d expect your transplants to spread at maturity if planting multiple trees, or situating them near other plants or structures.

Dig holes about as deep and a bit wider than the transplant’s root system. Toss an inch or so of compost into the hole and mix it into the soil with a cultivator.

Work an inch or so of organic matter – such as compost or well-rotted manure – into the soil that you’ll use to backfill the hole.

Remove the transplant from its container, lower it into the hole, and alternate backfilling with irrigation until the empty space around the transplant is filled with watered-in soil.

But before you pat yourself on the back for a tree well-transplanted, double-check to make sure that the root flare is visible above the soil line, with the graft point a few inches higher than the flare.

After backfilling, top it all off with a couple inches of mulch, kept well away from the trunk. Okay, now you can pat yourself on the back.

For transplanting into a container, you’ll be using a well-draining soilless media rather than garden soil, and your planting site will be a sturdy pot with drainage holes.

A 25-gallon pot about two feet in diameter should work nicely, as container-grown loquats will only grow to be about 10 feet tall, give or take.

How to Grow

So, you’ve got an E. japonica in the ground… Let’s break down its cultivation requirements, shall we?

Climate and Exposure Needs

As mentioned earlier, loquats are suited to USDA Hardiness Zones 8 to 10. Which totally tracks, given its subtropical origins.

Container-grown E. japonica has a broader range, as it can be grown year-round indoors as a houseplant or brought inside whenever temperatures dip below freezing.

For optimal fruiting and aesthetics, full sun is ideal. Although, in a pinch, loquats will tolerate partial shade exposures, like the kind that an understory tree might receive.

Soil Needs

Here’s the ideal prescription for a loquat’s soil: fertile and well-draining, with a pH of 6.0 to 7.0.

The fertility can be maintained by amending the soil in the root zone with an inch of organic matter every spring. But as long as the soil drains well and is relatively free of saline, these trees aren’t particularly picky about the soils that they sit in.

They can actually tolerate both acidic and alkaline soils, believe it or not. On the Texas A&M University website, Texas Cooperative Extension horticulturist Julian W. Sauls, PhD writes, “Soil pH does not seem to matter, as the trees grow equally well in the acid soils of east Texas and the alkaline soils of north, central, and south Texas.”

Water and Fertilizer Needs

With some moderate drought tolerance, a loquat needn’t be babied in the irrigation department.

But to yield the best possible fruits, it’s important to keep the root zone from drying out completely by watering whenever the top six inches of soil dry out.

Similarly undemanding with fertilizer, the tree can be fed nothing and it’ll do fine.

But an application of 6-6-6 NPK fertilizer three times throughout the growing season will definitely enable the tree to be more fruitful.

Growing Tips

- Full sun is optimal, but partial shade is tolerable.

- Well-draining soil is essential.

- Water whenever the top six inches of soil are dry.

Pruning and Maintenance

Pruning isn’t necessary to maintain a loquat’s shape – unless you’re growing one as espalier or something – but it can be helpful to maintain its size.

Regardless of dimensions, though, branches that are dead, dying, or otherwise damaged should be removed to maintain health and aesthetics.

Maintaining a few inches of mulch around the tree trunk will help to protect the roots, conserve moisture, and suppress weed growth.

Any fallen leaves, fruits, and twigs should be raked up as needed to maintain a relatively sterile and neat-looking environment.

Cultivars to Select

Don’t get it twisted: a standard loquat boasts amazing fruits and landscape aesthetics.

But if you’re looking for slight twists on an old favorite, then these three cultivars are fantastic starting points:

Champagne

Introduced in California by C. P. Taft in 1908 or so, ‘Champagne’ is an E. japonica cultivar that grows rather well in USDA Hardiness Zone 9.

Its fruits flaunt white flesh and yellow skin, and have a bit of tartness to their taste.

‘Champagne’

Just like its alcoholic namesake, you’re sure to associate ‘Champagne’ with royalty, fanciness, and the start of a grand ol’ time.

To kick off the party, ‘Champagne’ is available from Nature Hills Nursery.

Gold Nugget

Despite the name, ‘Gold Nugget’ has fruit that’s not really gold in color, but it is nonetheless valuable.

The ‘Gold Nugget’ cultivar yields particularly ample amounts of pear-shaped, orange-skinned, and orange-fleshed fruits with an especially sweet taste.

‘Gold Nugget’

For fans of high yields of sweet orange deliciousness, ‘Gold Nugget’ is available for purchase from Nature Hills Nursery.

Variegata

If you’re trying to grow an E. japonica primarily for its looks rather than its fruits, ‘Variegata’ is the obvious choice.

Its leaves rock a creamy white variegation that’s intermixed with stunning pale green hues.

And if you’ve ever wanted to grow a loquat indoors, ‘Variegata’ makes for a rather attractive houseplant.

Managing Pests and Disease

Many plants worth growing are attractive to pests or pathogens, and loquats are no exception. If you wish to keep yours safe, then you’ll need to load up on some know-how beforehand.

Birds

When it comes to winged annoyances, it’s not just just itty-bitty bugs you have to worry about.

If given the chance, birds will swoop in and have a taste of your E. japonica fruits. But in my opinion, loquats are too tasty for use as bird feed.

When dealing with birds, it’s best to scare them with visuals or sounds.

Shimmery reflective tape, scare balloons, fake hawks, noise machines, and banging and clanging metal are all solid starting points.

But the most important thing to remember is variety – birds will get used to any one deterrent pretty quickly, so be sure to switch up your scare tactics every week or two.

Insects

In case you need extra motivation, insects can spread pathogens as they feed. Want to control disease? Then you can’t ignore pest management.

Aphids

A common foe of the gardener, aphids are soft-bodied, translucent, and less than an eighth of an inch long.

With piercing-sucking mouthparts, aphids extract the phloem from leaves, which can leave foliage with wilting, chlorosis, and stunted growth.

Additionally, aphids excrete honeydew, which can attract ants and lead to the development of black sooty mold. Not a good look, especially on fruits.

Strong sprays of water can physically knock the pests off of infested surfaces, while sprays of horticultural oil or insecticidal soap can snuff them out.

Bonide All-Seasons Horticultural Oil

Bonide offers ready-to-use sprays of horticultural oil in ready to spray quart bottles, and 16-, 32-ounce, and gallon concentrate from Arbico Organics, while Natria sells a ready-to-spray insecticidal soap that’s available via Amazon.

Read more about managing aphids in our guide.

Scale

A diverse group of bugs, scale are small, rounded insects that are either armored with a protective shell or soft-bodied and covered with waxy secretions.

Sucking sap from infested plant surfaces, scale can cause dieback, chlorosis, and stunted growth, especially in large populations.

Similarly to aphids, soft scale also excrete honeydew, which comes with ant attraction and the risk of black sooty mold.

Control for scale is similar to that for aphids. Any heavily infested tissues – i.e. areas where you can hardly see the plant underneath the scale – should be removed and destroyed.

Learn more about scale in our guide.

Spider Mites

The smallest pests on our list, spider mites can barely be spotted with the naked eye.

Break out a Sherlock Holmes-esque hand lens, and you’ll notice that their oval-shaped bodies are covered with translucent, bristly hairs.

Not that you’ll need to, though – the webs they weave are the primary indication of their presence.

Sprays of insecticidal soap should do the job, control-wise. Discover more control tactics in our guide to managing spider mites.

Disease

Since sickness can spread all too easily in the garden, it’s essential to be sanitary: clean your tools, use disease-free soils, and avoid planting pathogen-infected specimens, no matter how minor the infection may be.

Fire Blight

While not as common in loquats as it is in pears or quince, fire blight definitely deserves a brief 101.

Caused by the bacterium Erwinia amylovora, fire blight symptoms begin with small cankers that ooze a light tan fluid that darkens with air exposure.

The disease is transmitted to the leaves, fruits, and flowers, which turn brown, black, and shriveled.

These structures often hang from the tree in their shriveled discoloration, with a scorched appearance that earned the disease its name.

Infected wood is streaked with patches of pink to orange-red, which desiccate, crack, and become sunken with time.

The disease optimally spreads in moisture and in temperatures of 75 to 85°F. When both are present, disease management is quite difficult.

Infected wood must be pruned with sterile tools in spring as symptoms become apparent. Be sure to make your cuts at least six inches below infected areas.

As vigorously-growing tissues are especially conducive to fire blight spread, avoid the use of high-nitrogen fertilizers.

Heavily infected specimens should be uprooted and destroyed.

Leaf Spot

Caused by the fungus Entomosporium mespili, Entomosporium leaf spot causes small reddish spots on loquat leaves, which grow and darken with age.

A lighter, spore-forming body eventually forms in the center of each spot, leading to further disease spread.

As the disease spreads via splashing water, be sure to avoid overhead irrigation. Remove and pitch any infected leaves, both from the tree and on the ground.

If Entomosporium leaf spot is a particular problem in your area, sprays of copper fungicides are an effective preventative measure.

Scab

Primarily caused by Fusicladium eriobotryae fungi in loquats, scab manifests on the plant as green to olive-brown spots that coat fruits and leaves, severely reducing edibility and aesthetics.

Mild temperatures and moisture are conducive to disease spread, while dry weather slows it down.

Infected fruits and leaves should be raked up and disposed of when they fall. To reduce disease-conducive moisture, avoid overhead irrigation and prune to improve inter-canopy airflow.

For further prevention, a protocol of rotated fungicides, sprayed from bud break to a month post-petal fall, can be effective.

Best Uses

To be honest, a loquat’s tasty fruit provides all the motivation one needs to grow these trees, whether they’re grown orchard-style, espaliered, or even by themselves as solitary plantings.

But aside from its yields, E. japonica looks gorgeous as an ornamental planting, which comes in handy when growing these guys in spots where it’s too hot or cold for decent fruit production.

Grown as a specimen, an accent, near a patio, or by the street, it doesn’t matter. This tree is beautiful pretty much everywhere.

The flowers and leaves also amaze and astound in floral arrangements!

Harvesting

Loquat fruit needs to ripen fully on the tree before you harvest it.

You should have ripe fruit on your hands sometime in spring, or about 90 days after the tree’s flowers are fully open.

You’ll know it’s harvest time when the fruit is slightly soft and a full yellow to orange, without any green.

At this point, you should use pruners to remove the fruit from the stem. You’ll want to gently harvest them as quickly as you can as soon as they are ready, because they can be quite messy if they fall.

They are most delicious when eaten or prepared right away, although they can keep for a week or two in the fridge. Like you would with an apple or pear, make sure to avoid consuming the seeds!

Preservation

But perhaps you want to enjoy the fruits of your labor for longer than a measly one to two weeks. In that case, you’ll need to freeze your fruits, or make some tasty loquat jam!

To freeze loquats, you’ll first need to wash them. After that, remove the stems, blossom ends, and seeds.

Place the fruits in plastic containers with lids or durable freezer bags. Then, add a liquid simple syrup of 30 percent sugar and 70 percent water to your container. Allow a half-inch of empty headspace since the liquid will expand when it’s frozen.

Put in the freezer, and boom! You’ve got loquats that will stay tasty for months instead of weeks.

Alternatively, you can preserve the fruits as a jam. Loquats are high in natural pectin, so they are easy to preserve.

Canning is one option, or you can make freezer jam like this version from Gena Bell, defrosting what you need prior to use.

With just a few simple ingredients and cold storage, you’ll be able to enjoy loquats at any time of year. Get the recipe at Live Love Laugh Food.

Recipes and Cooking Ideas

Although you can certainly eat them on their own, ripe from the tree, loquats also work wonderfully in more elaborate culinary creations. For some tasty ideas, read on.

Apple Crumble

For a tasty and unusual dessert, consider this delicious loquat apple crumble recipe from Peter’s Food Adventures.

As members of the same family, apples and loquats get along well, pairing together perfectly in this easy-to-make dish.

Refrigerator Pickles

Amy Finley, winner of the third season of Food Network’s “The Next Food Network Star” cooking competition, shared this recipe with her friend Caron Golden of the website San Diego Foodstuff, and Golden shared it with us!

After you make the pickles, you’ll have to let them chill in the refrigerator for at least five days before digging in – seven if you can stand it!

Vinaigrette

This tasty salad dressing comes from a Charleston, South Carolina-based food blogger who specializes in paleo cooking.

Jessica recommends you use a high-quality olive oil in this dressing, which includes dijon mustard and oregano in addition to loquats.

Find the recipe from Paleo Scaleo.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Evergreen fruit tree | Flower/Foliage Color: | White/dark green |

| Native to: | China | Maintenance: | Moderate |

| Hardiness (USDA Zones): | 8-10 | Tolerance: | Acidic soils, alkaline soils, moderate drought, partial shade |

| Bloom Time/Season: | Fall to winter (flowering), winter to spring (fruiting) | Soil Type: | Fertile |

| Exposure: | Full sun | Soil pH: | 6.0-7.0 |

| Time to Maturity: | 3-10 years (fruiting) | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Spacing: | 10-25 feet apart, 25-30 feet from structures | Attracts: | Birds, insect pollinators |

| Planting Depth: | Depth of root system (transplants) | Uses: | Accent, floral arrangements, fruit production, houseplant, specimen, street tree |

| Height: | 10-25 feet | Order: | Rosales |

| Spread: | 10-25 feet | Family: | Rosaceae |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Genus: | Eriobotrya |

| Common Pests and Disease: | Aphids, scale, spider mites; fire blight, leaf spot, scab | Species: | Japonica |

You Really Ought to Try Loquat

If you’re a fruit fan, it’s definitely worth checking off the bucket list. I mean, given its scrumptious taste, you just gotta!

Plus, the relative rarity of loquat fruit on grocery store shelves should add to the appeal of cultivating the tree yourself. Consider it a botanical and culinary adventure!

Do you have E. japonica in your landscape? We’d love to hear about your experiences – please share in the comments section below.

If you’re interested in finding more information about growing fruit trees, check out these guides next: