I’m stopped at the roundabout. An elderly couple waits at the kerb and I wave them across. It’s no virtue on my part. The give-way rule that obliges me to wait for cars, if not people, gives them time. Yet the man gives me a smile of unwarranted gratitude. Then he grabs his wife’s arm and shuffles her gently across. It makes me mad. Not because I have to wait, but because our system renders pedestrians supplicant.

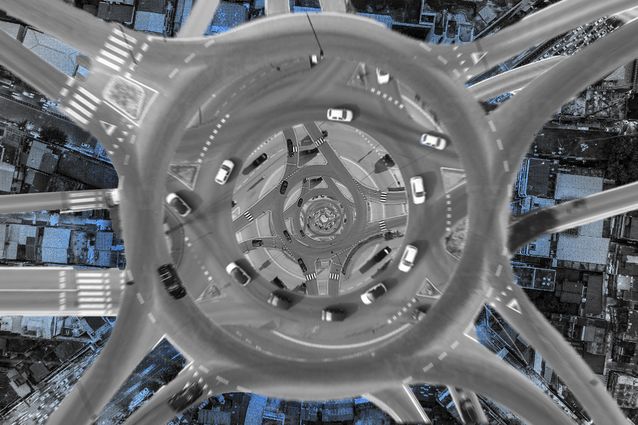

The classic suburban roundabout is a device of some ingenuity. If traffic flows are perpendicular and fairly even in each direction, it offers a seamless way to keep everyone moving in a relatively equitable fashion. But, as in a Greek tragedy, this same virtue is its fatal flaw, marking out the roundabout as an instrument of the devil.

Most commentators are very much in favour. Engineers, councils, drivers – most people agree that roundabouts are faster, smoother, safer, fairer, more civic-minded, better for the environment and for pedestrians too. But are they?

The roundabout has a long history, predating the motor vehicle. The most famous early instance was designed by French architect and planner Eugène Hénard in 1907. This is the one-way circular traffic system that encircles the (much earlier) Arc de Triomphe at the centre of what is now the Place Charles de Gaulle in Paris. (Personally, I prefer its earlier name, the Place de L’Étoile – “Square of the Star” – because it embodies the singular charm of this twelve-way roundabout.)

But Hénard took the concept of a one-way circular traffic flow from an earlier, British idea, as presented to the London County Council in 1897 by British engineer Michael Holroyd Smith. Inventor of the electric tramway and the underground electric train, Holroyd Smith told the LCC that congestion issues like those at London’s Ludgate Circus could be resolved by “gyratory traffic flow.”

It happened that these conversations broadly coincided with the advent of the suburb. Having published Garden Cities of To-morrow in 1898, British urban planner Ebenezer Howard spent the next three decades building the garden city movement and publicizing his suburban ideals via lecture tours and similar polemical activities. The roundabout was a perfect fit.

True, Howard did not intend the circles-within-circles geometry that characterizes his garden city diagrams to translate literally. The towns and cities so generated were not intended to be circular; nor were the concentric rings that mark their every major intersection necessarily meant to imply roundabouts. Still, the resemblance is unmistakable.

Canberra, Australia’s mega-scale homage to the roundabout, replicates Howard’s drawings to an uncanny degree – and there are connections. The Griffins’ Canberra plan had evolved from Pierre L’Enfant’s 1791 plan for Washington, which grew, in turn, from Haussmann’ radial restructure of Paris. (Indeed, L’Enfant gave Washington several square-form roundabouts that possibly prefigure Hénard’s 1907 reworking of the Place de L’Étoile.) Be that as it may, it was the mid-century suburban explosion that really kicked the roundabout into life as a traffic-soothing device.

A guiding purpose of both the L’Enfant plan and the Griffin plan was to reify the egalitarian belief that (to quote L’Enfant’s biographer Scott Berg) “every citizen was equally important.” The roundabout seemed to symbolize that belief, giving all drivers equal rights and access. Canberra’s ubiquitous roundabouts seem to do exactly that, at every scale – from the small, local intersection to the vast, village-sized roundabouts of Civic and the poignant symbolism that puts our parliament house itself at the centre of a vast concentric roundabout. Everyone is equal – except the pedestrian.

These days, every suburb of every Australian city and town sports a spreading rash of roundabouts. Traffic engineers are in thrall. So, apparently, is every local council, planner and urban designer. But in truth, this brilliant reinvention, like so much of modernism – the strip window, the open plan, the motorway – achieved its brilliance at the expense of human reality. In particular, the roundabout conveniently overlooks diversity of mode, mood and character, hugely prioritizing a mode monoculture: the car.

The putative benefits of roundabouts are several. Drivers need to check and give way only in one direction. Often, they needn’t actually stop but can simply slow down, thus retaining some momentum. This results in vehicles generating less noise and carbon. Roundabouts enable U-turns and offer de facto left-turn slip lanes. They are fast, whizzy and convenient, and never make you wait (as a red light does) in the absence of opposing traffic. The roundabout thus endows the urban landscape with a lubricated quality – a pleasant sense of slipperiness.

But this slipperiness is also its devilment. The roundabout lulls us into smugness and tempts us into arrogance. How?

First, it is really only effective where traffic volumes are low and the opposing traffic flows are pretty equal. In high-traffic situations, or where one flow is dominant, the egalitarian factor is lost. Where the traffic flows are dramatically unequal, the vehicles in the lesser flow are disadvantaged and the dominance of the main flow self-perpetuates. This pattern, of the strong being strengthened at the expense of the weak, takes us back to my elderly pedestrian couple.

In the case of big, busy roundabouts, especially when the circle itself is multi-lane, you have the distinct feeling of taking your life in your hands as you enter, even as a car. Some drivers become almost paralysed, finding it difficult or impossible to take the leap as heavy-laden lorries bear down on them. For pedestrians, it’s worse still.

Advocates argue that the roundabout benefits the pedestrian because they need only look in one direction. But there’s sophistry here – partly because one-way traffic is faster (viz. motorways) and partly because roundabout traffic is one-way only if the pedestrian is crossing onto the middle island. In this case, said pedestrian must make the crossing again to get off the island. Such a strategy carries its own dangers, since many vehicles (especially the biggest ones) travel blithely overland, across the island. If, on the other hand, the pedestrian crosses where the road joins the roundabout, the traffic is two-way and under reduced obligation to stop.

All this, in any multi-lane or even moderate-traffic situation, renders the whole experience thoroughly intimidating, even to the most agile of pedestrians – precisely because of the delicious sense of privilege and entitlement that the roundabout’s slipperiness gives the motorist.

However you approach it, on two feet or four wheels, the roundabout demands of the road user a level of cocky self-advocacy that many – the old, the weak, the slow and the timid – cannot and should not have to supply. The roundabout is neoliberalism in action. The strong devour the weak. Get on yer bike!

After 30 years of this rampant social Darwinism around the globe, we now see the misery at the end of that road. Cities are for everyone. That’s fundamental. For too long, we’ve handed our streetscape holus-bolus to the traffic engineer and the car. Walking invigorates streets, is carbon-free, builds community and enhances public health. In fact, of all transport modes, walking is the most ancient, healthy, and (taking into account the health benefits, retail spend, tourist attraction, environmental benefits and property-value enhancement) economically beneficial.

So the pedestrian, far from being an afterthought under constant threat from roundabout paralysis, should be prioritized. Enough already. Our cityscapes should endow us all, including the frail and the flawed (because aren’t we all?) with blithe confidence of passage.