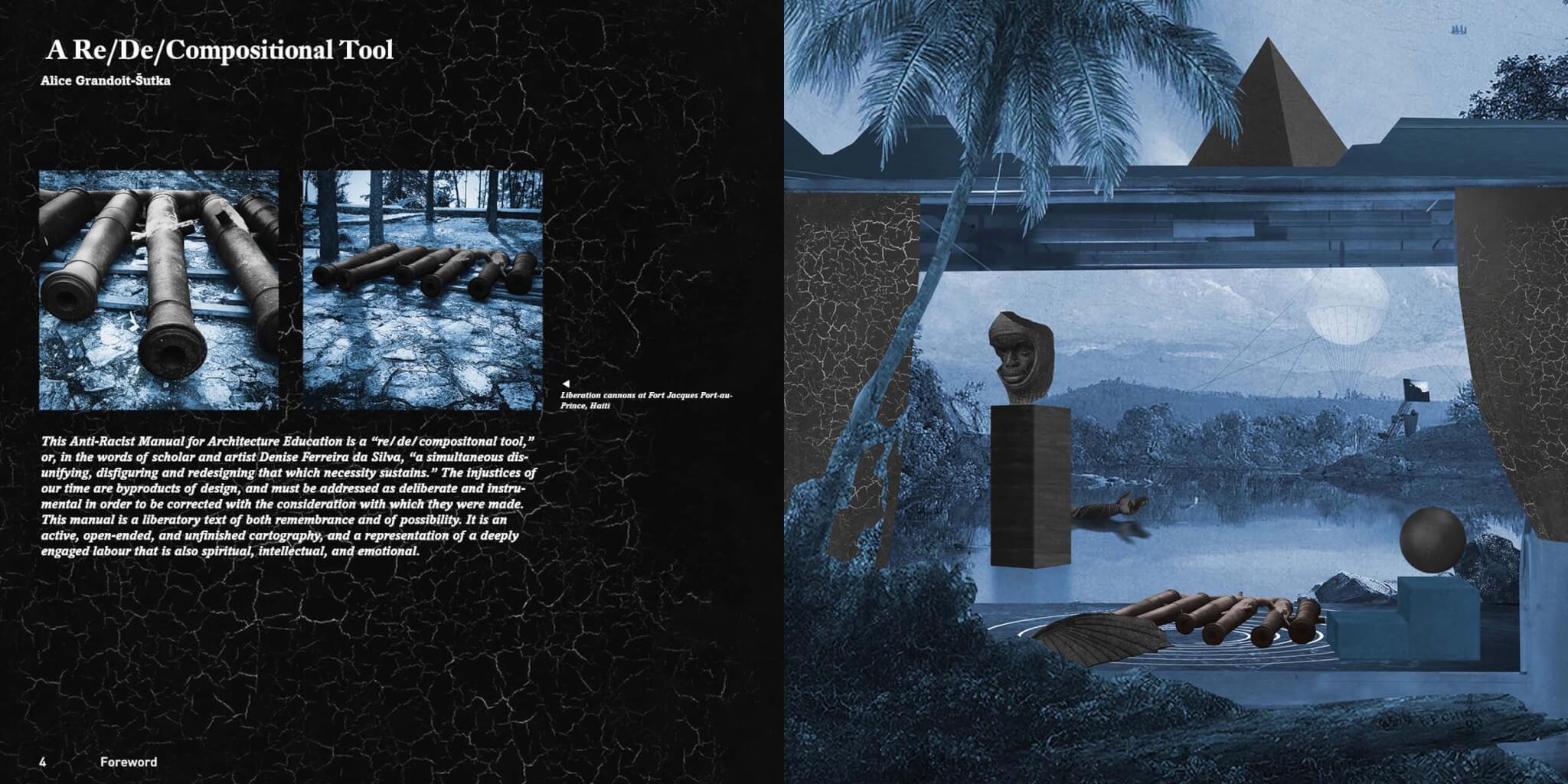

“Anti-racism is not taught. Anti-racism is practiced,” reads the epigraph of A Manual of Anti-racist Architecture Education. Written by Cruz García and Nathalie Frankowski of WAI Architecture Think Tank, the new publication is a slim edition bound in glittering black cloth that offers architects a set of tools, frameworks, and orientations that support antiracist practice and liberatory futures of “both remembrance and of possibility” in pedagogy and beyond.

WAI Architecture Think Tank is a planetary studio—referring to its international reach, interdisciplinary practice, and political alignment beyond human systems—founded by Puerto Rican architect, artist, curator, educator, author, and theorist Cruz García and French architect, artist, curator, educator, author, and poet Nathalie Frankowski. The studio has excelled in all traditional aspects of practice and research: García and Frankowski have practiced internationally, taught across accredited architecture institutions, and exhibited widely in museums and biennials. Their ideas have been shared in coedited books and in respected peer-reviewed journals. However, this is not their primary stated objective. Rather, WAI as a “think tank” has pushed the boundaries of prescriptive paths for any ambitious studio or practitioner through its emphasis on antiracist and postcolonial critique, public engagement, and collective knowledge production. Consistent with these aims, the Manual (also made freely available in Spanish and English on WAI’s website) is meant to be supportive text in relation to WAI’s own platforms, courses, and interventions as well as more broadly within and beyond architectural institutions.

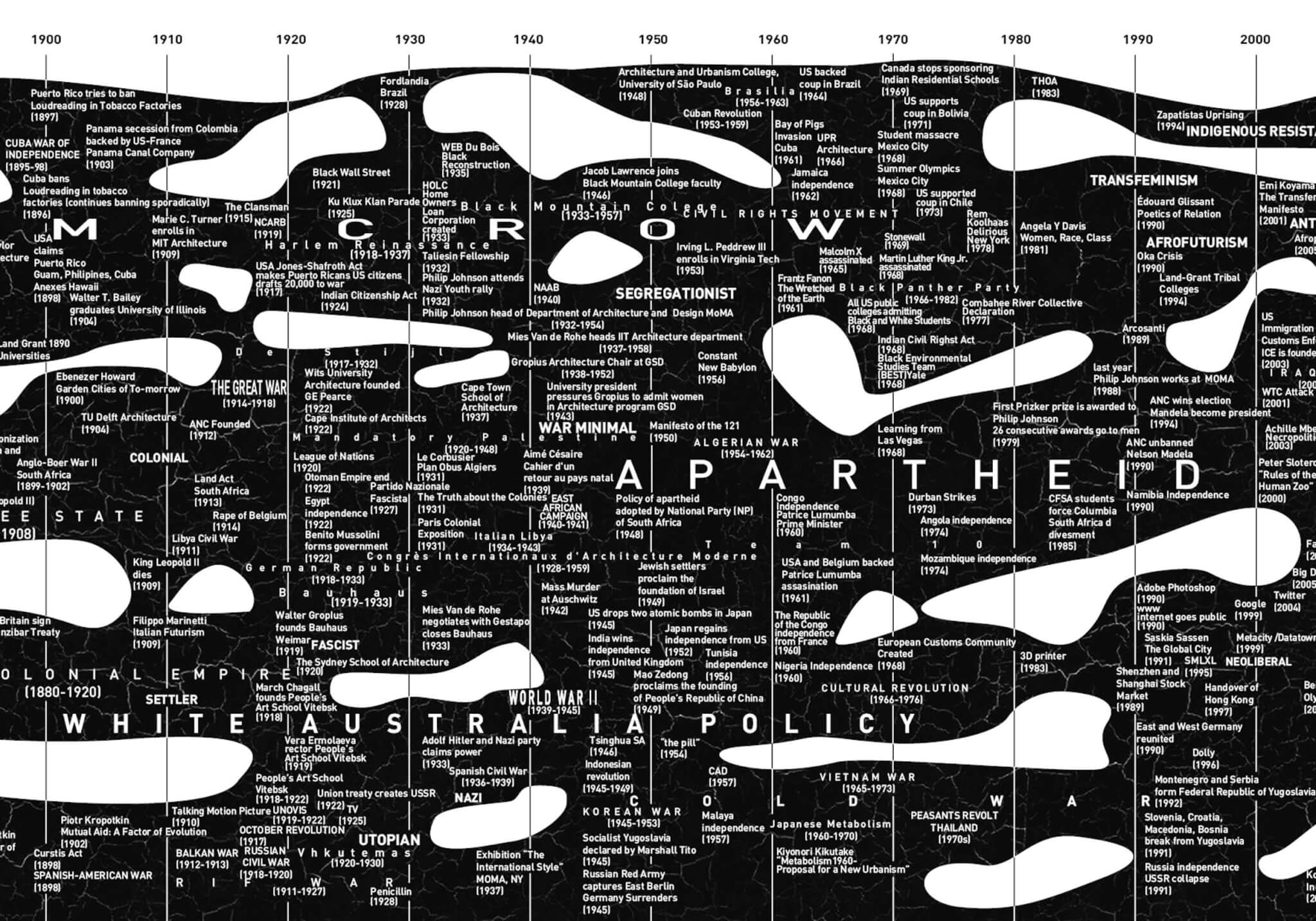

Continuing this work, the Manual approaches the framework of antiracism praxis in design pedagogy through three distinct vantage points: Before, During, and After architectural education. These are shared using three distinct devices, respectively: an essay, an annotated diagram, and a manifesto. This structure suggests that chapters can be read in sequence, or as a guide for readers to explore within our own unique contexts and scenarios. In deliberately framing its research, writings, and analysis as a “manual,” WAI offers this book as a companion for students, educators, and spatial practitioners to keep close at hand. And by varying its approaches to each chapter, WAI models the abundantly varied ways we might explore our world with a recursiveness that echoes the rhythms of the decolonial oral and written traditions from which they draw.

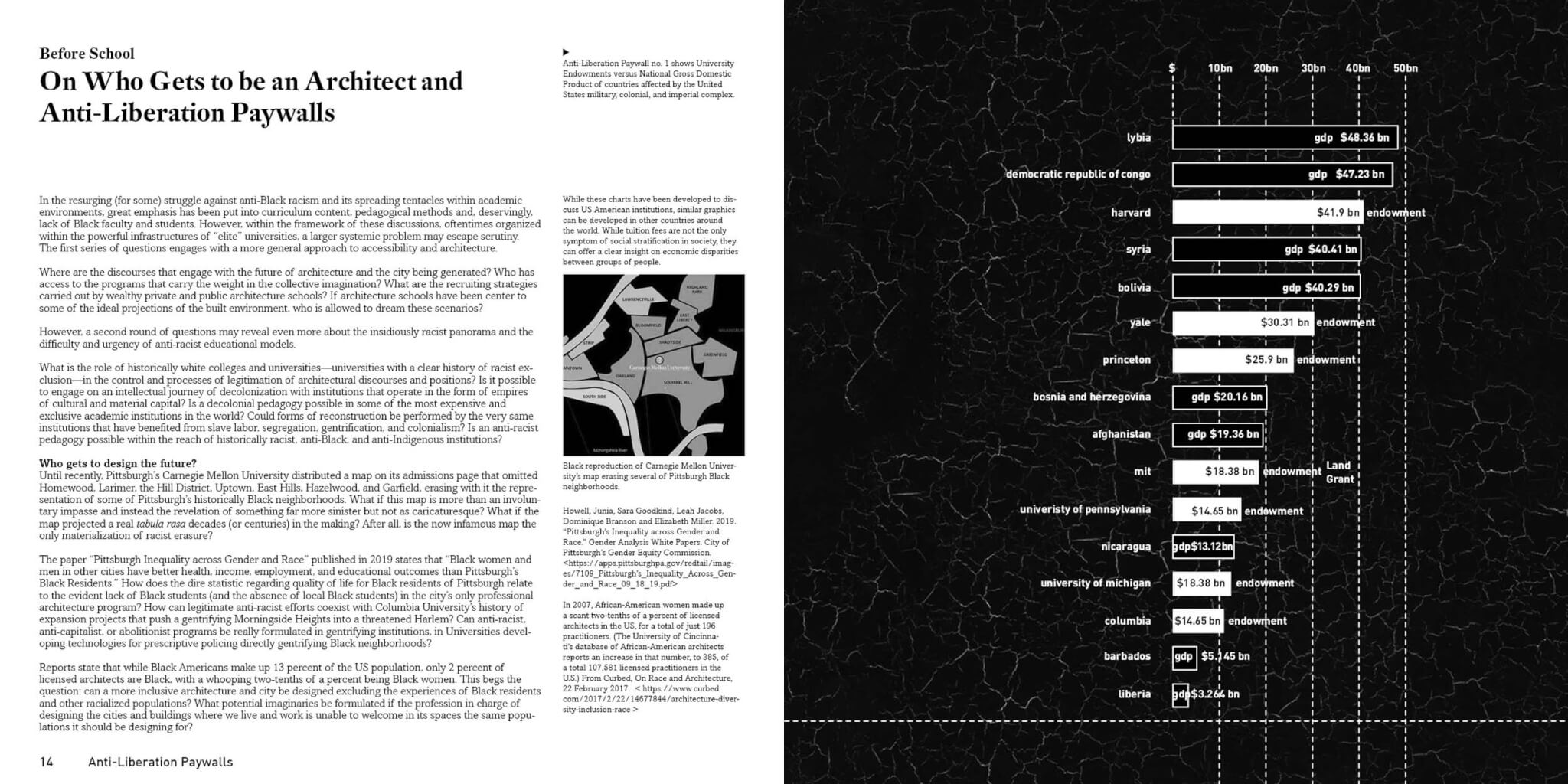

In the first chapter, “Before School: On Who Gets to Be an Architect and Anti-Liberation Paywalls,” the Manual unveils systemic barriers to entry, contrasting tuition fees for elite architectural institutions across the United States with median household incomes in their respective cities, as well as endowments compared with the GDPs of entire nations. This chapter builds off the stark simplicity of this material stratification to demonstrate that not only do universities perpetuate exclusion along lines of class and race but they themselves are settler-colonial tools of land occupation, gentrification, and racial oppression.

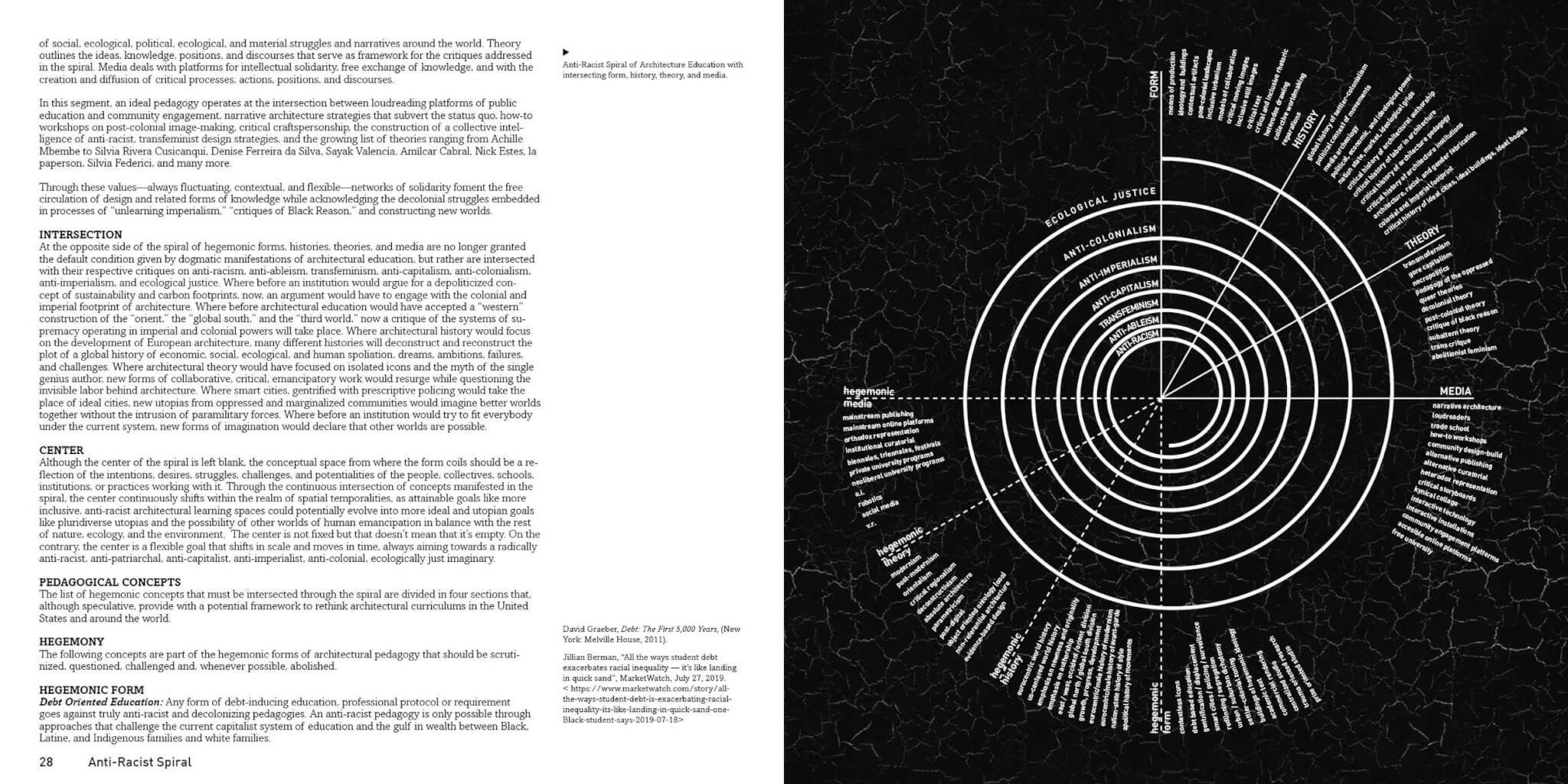

Meanwhile, “During School: An Anti-racist Architecture Education Spiral” introduces the Anti-racist Spiral as a postcolonial tool that both engages critically with and ultimately decenters Western architecture canons by providing alternate lineages of form, history, and theory. Drawing deeply from radical (from the Latin radix for root) thinkers and practitioners across the world—from Édouard Glissant and Frantz Fanon to Kimberle Crenshaw, Angela Davis, and the Combahee River Collective; from Achille Mbembe to Leanne Betasamosake Simpson to Paul B. Preciado and many others—WAI zeroes in on the Anglo-Saxon roots of the architectural discipline, the violences it has embedded in our built environments, and its ubiquity in contemporary architectural curricula. In directly addressing specific canonical forms, histories, theories, and media, and presenting them alongside an inventory of tangible pedagogical alternatives, WAI provides a play-by-play for radically transforming architectural pedagogy today: One can easily see both studio or seminar professors lifting suggestions from this chapter, one following another.

Finally, “After School: Un-Making Architecture, an Anti-racist Architecture Manifesto” uses the provocation of “un-making” to visualize gaps and omissions that arise when our discipline becomes “too obsessed with making” within oppressive systems. Here, for everyone who considers themselves a practitioner, the Manual provides several starting points for understanding how world-shaping narratives—which give architecture power and credence and which are in turn shaped by architecture—have historically been made and thus can be collectively “unmade.”

The text concludes with an appendix, “Against the Precarization of Anti-racist Education Labor,” which poses a series of questions on the labor of education. Itself a form of labor, this book offers a reflexive moment of contemplation and an invitation to continue the conversation beyond these pages. Those reading closely may even start to recognize García’s and Frankowski’s own experiences in practice. For instance, their investigations into Pittsburgh’s racial segregation in relation to admissions office erasures of Black neighborhoods by Carnegie Mellon University, where they held visiting professorships, or into Harvard University’s outsize role in profiting off Puerto Rican debt, part of a $41.9 billion endowment compared with the total $450 million budget of García’s alma mater, Universidad de Puerto Rico.

A Manual of Anti-racist Architecture Education challenges us to critically engage with contradictions inherent to architectural practice and education within late capitalist settler colonies through individual practice. The tools WAI offers are both politically potent and deeply optimistic. Throughout, WAI references Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang’s essay, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor.” García and Frankowski, too, are not speaking in metaphor. There is clarity in their critique of both the historical formations of syllabi and of campuses themselves—allowing us to behold the same systems threading through each scale. For a discipline known for both technical and theoretical prowess in working across scales, this antiracist approach can, and should, be our baseline for practice.

Bz Zhang is an architect and artist based on Tongva land (so-called Los Angeles), where they wonder aloud about representations of violence and the violence of representations by asking questions both using and about disciplinary tools of art and architecture. In their free time, they look for birds and trash in the Los Angeles River.