[ad_1]

I “discovered” Leiviskä’s work in 1991 through one of his ecclesiastical designs, the Myyrmäki Church and Parish Center at Vantaa outside Helsinki (1980–84). Genuine architecture communicates before it is understood: It touches the mind and the senses at levels beyond words and out of range of theoretical justifications. I was overwhelmed immediately by the sublime light, vibrant space, and “musical” rhythms of floating planes. I was convinced that I was in the presence of a masterpiece. I remember visiting the place with Balkrishna Doshi, the Indian architect, who was also overwhelmed and said: “Why is it that we do not know more about this architect? It is so much better than most of what is going on.”

A year later, I recorded my reaction in a text published in the Finland Builds 8 book entitled “Concepts and Continuities.” This explored several strands of modern architectural tradition in Finland and brought Leiviskä’s Myyrmäki Church into high focus. Subsequently I included the building in the third edition of Modern Architecture Since 1900 (Phaidon, 1996) where it stood along other outstanding buildings of the period by masters such as Tadao Ando and Álvaro Siza. As usual I attempted to balance firsthand experience of buildings, with careful analysis of intentions and a reconstruction of the architect’s place in longer traditions, including those of modern architecture, which I conceived of as a delta with many streams.

Leiviskä’s work evades facile historical and critical categories. Born in Helsinki and educated at Helsinki University of Technology, he, across his career of 60 years, established a unique family of forms, a personal style, but from this he generated a wide range of buildings each with a unique identity of its own. Some of these have entered the annals of world architecture as masterpieces—one thinks particularly of the aforementioned Myyrmäki Church or his Männistö Church at Kuopio (1986–92)—both distinguished by their sublime fusion of light, sacred space, and geometry.

But Leiviskä also had a secular side, working up and down the scale from small residences to collective housing, from the German Embassy in Helsinki (1995) to the Dar al-Kalima Academy in Bethlehem (2002), from the Villa Lepola at Espoo (1998) to the Swedish School of Social Sciences in Helsinki (2009). On each occasion he sought an appropriate character for the human activities enclosed and for the place where the building stands. Whether designing a space of public assembly, a stair in a private villa or a kitchen in a public housing scheme, he brought the same attention to the task, endowing day to day activities with a touch of poetry.

Leiviskä treated natural and artificial light as architectural materials and aspired to the harmony of nature in his search for authentic forms. He had no time for the superficialities of postmodernism or for the easy tricks of neo-modernist formalism, and still less for the facile imagery of “iconic” fashion: His work was driven by a social vision and a core of architectural principles. Leiviskä dug deep into the essence of the architectural art, especially in his handling of polyphonic spaces experienced over time. He declared:

I believe in the permanency of the basic features of architecture, the so-called eternal values. I do not therefore believe that there has been anything in recent years which could revolutionize the basic tenets of architecture and its central task.

Leiviskä interpreted the social conditions, climate, and landscapes of Finland via an intense abstraction. He extended primary lessons of Aalto’s work into new expressive territories and in doing so enriched a complex modern Finnish tradition. His buildings, with their overlapping planes and stratified forms, resemble abstractions of landscape or luminous forest clearings, while his interlocking voids and abstract plans call to mind the paintings of de Stijl artists like Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg. His constant touch-tone in the past was the Bavarian Baroque as exemplified by the sublime light and layered surfaces of the mid–18th-century Neresheim Monastery by Balthasar Neumann. For Leiviskä, the past was ever present, a fund of knowledge, memories, and impressions to be metamorphosed in his own art.

Leiviskä aspired towards what he felt were timeless values in the history of architecture. Here his deep knowledge and feeling for great classical music were an indispensable aid. Leiviskä often said that he had initially hoped to be a professional pianist but instead became an architect channeling music into another medium and another art form. He stated:

Architecture is closer to music than to the visual arts. To qualify as architecture, buildings together with their internal spaces and their details, must be an organic part of the environment, of its grand drama, of its movement and its spatial sequences. To me a building as it stands ‘as a piece of architecture’ is nothing. Its meaning comes only in counterpoint with its surroundings, with life and with light.

The one building that Juha Leiviskä designed outside Finland was the Dar al-Kalima Academy (2003) in the Old City of Bethlehem, a cultural institution fostering social activities in the Palestinian community but open to all. Leiviskä conceived this as sort of urban landscape of terraces and skylights skillfully inserted into the historic context and attuned to the stone buildings and the local climate which required shade and protection against the sun. It is a place of calm and reconciliation. Juha himself referred to the project in moving terms: “On a personal, emotional level, it is perhaps my most important achievement. I left my heart in Palestine.” Leiviskä’s spirit lives on in the sublime spaces filled with light of his buildings. They will touch and inspire future generations who will be moved by the silent music of his architecture.

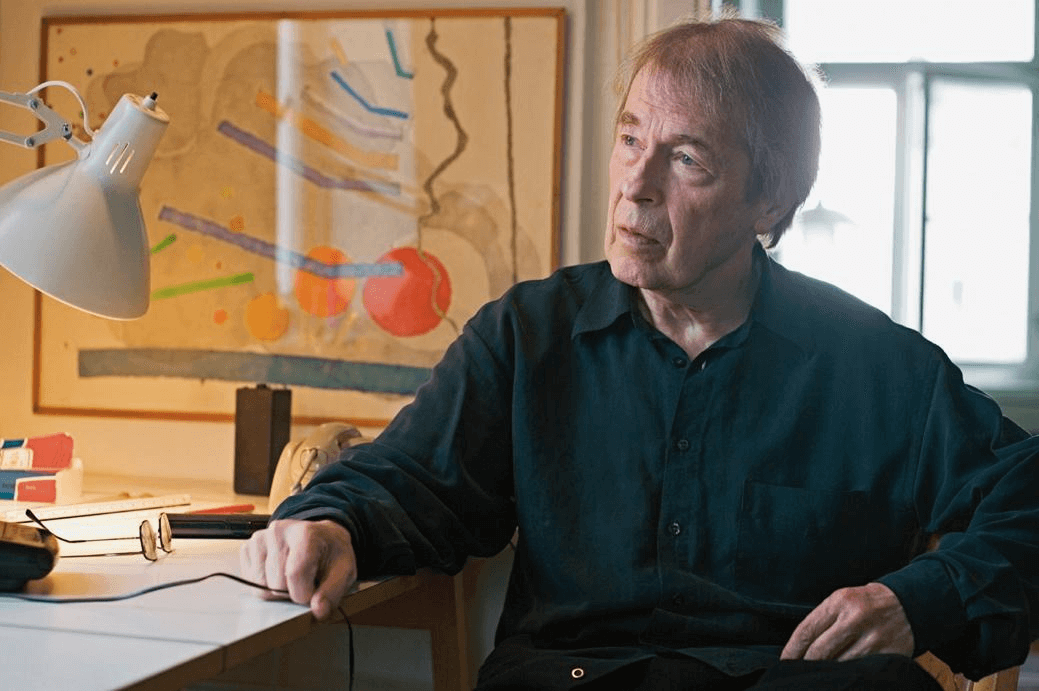

William J. R. Curtis is the author of Modern Architecture Since 1900 and Le Corbusier: Ideas and Forms, both considered classics. He has written seminal texts on Finnish modernism, Alvar Aalto in particular. In 2000 the Museum of Finnish Architecture, Helsinki, exhibited his paintings and drawings under the title Mental Landscapes; in 2007 the Alvar Aalto Museum, Jyvaskyla exhibited his photographs in Structures of Light; and in 2006 Curtis was honored with a Medal by the MFA for his services to architecture.

[ad_2]

Source link