[ad_1]

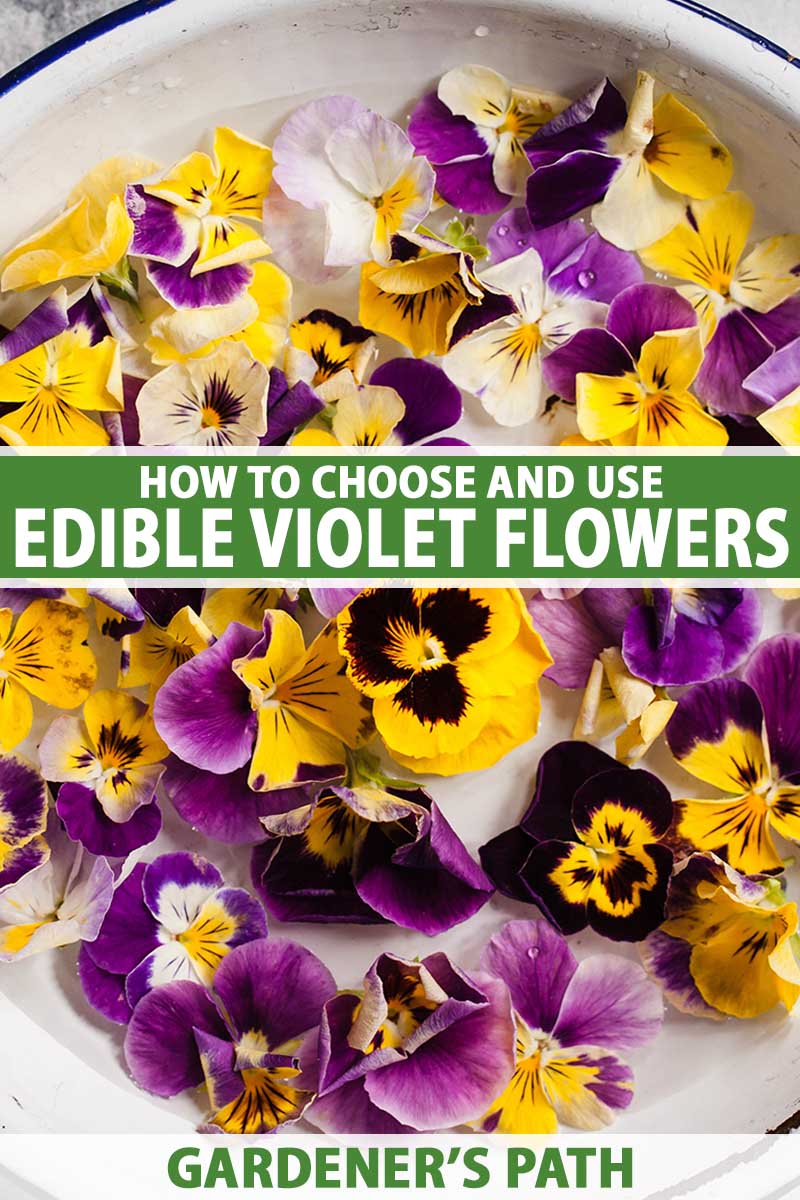

I won’t leave you in suspense: violets are edible. You might have already guessed that. Most of us have seen them candied and decorating cakes or in drinks.

Not only are they edible, they’re palatable!

Some plants are technically edible, as in they won’t hurt you to eat them, and they might even provide some nutrition.

But other flowers and ornamental plants, like violets, could be grown purely for their flavor.

You can even find cut flowers and live plants at gourmet grocery stores that are cultivated solely for munching on.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Whether you buy some at the store ready to eat or to cultivate at home, or you forage them from the wild, these cheerful harbingers of spring are a delight on the plate.

In this guide, we’ll explain which parts you can eat and how to identify wild plants, and offer up a few recipes to get you started.

Here’s the full lineup:

If you purchase a plant at a nursery, unless they can assure you that the plant hasn’t been sprayed, don’t eat any of the existing flowers.

Pinch them off and let new ones form. You can safely eat those.

If you decide to forage your goodies, don’t take too many from one area and be sure only to forage in areas where it’s legal and safe to do so.

Don’t eat any foraged foods unless you know whether they have been sprayed or not, and avoid those growing on the side of the road. You never know what kinds of chemicals or animal waste has touched them.

Speaking of, if you’d like to learn about some more edible flowers, read our guide. And be sure to check out our guide to harvesting and storing edible flowers as well!

A Short History of Edible Violets

Violets were one of the first flowers to be cultivated as food and medicine.

Ancient Greeks and Romans drank violet wine and used the petals to make syrup and preserves. They also used them in desserts and salads.

In North America, indigenous people used western dog violets (V. adunca) to lessen swelling or stomach pain, and to ease labor pains.

Field pansies (V. bicolor) were used for headaches, colds, and coughs. Marsh blue (V. cucullata) and downy yellow violets (V. pubescens) were used to treat boils, coughs, and dysentery.

It wasn’t until much later that people started to appreciate them solely for their ornamental value.

In the 1700s in France, they were revered as an elegant addition to a meal, and women wore violet perfume, which was sought-after across Europe.

In England, the flower was associated with modesty and fidelity, and that’s where the term “shrinking violet” emerged to describe a modest, shy person.

Queen Victoria had her garden stocked with violets at all times for use in syrup, jelly, desserts, and tea.

In mid- and late 20th century America, mimicking the fine French cooking they’d heard about, housewives topped cakes and salads with delicate violets as a sign of their taste and culinary prowess.

What Parts of the Plants Are Edible?

Both cultivated and wild species are perfectly fine for the dinner table. Not only that, but you can eat the leaves, too. Don’t touch the roots, though.

Some species do have edible roots, and a few, like V. sororia, have large tubers. But others can make you sick. Best to just ignore them. And if you leave them in the ground, new plants will emerge.

The leaves have a mucilaginous, gummy texture, particularly when cooked. It’s less noticeable in young and uncooked leaves. Test them out before you commit to an entire salad, since some people don’t dig the taste or texture.

These plants are full of vitamins A and C and gram-per-gram have more than oranges and spinach.

They’re comprised of alkaloids, anthocyanins, cumarins, flavonoids, melatonin, and salicylic acid, all of which combine to provide some amount of neuroprotection by increasing antioxidant activity and reducing inflammation, which is a fancy way of saying they can be good for your brain.

Eaten in excess, the leaves and flowers can have a laxative quality, so watch out.

They contain saponins, which can cause stomach upset and diarrhea. These organic chemicals are more concentrated in the roots, which is why you probably don’t want to mess with them.

Which Ones Taste Best?

Taste is subjective, of course, but I find wild types to taste the best. Cultivated plants are usually bred for their appearance, not their flavor, unless you find the ones bred for eating.

That said, I know plenty of people who like cultivated types better because the flowers are larger and usually more fragrant. I’m more partial to bitter flavors and not sweet ones, so to each their own.

If you want something more floral and sweet, smell the flowers. If they have a distinct fragrance, they will probably also taste more floral. Some of the wild ones lack fragrance and have a more bitter profile.

Try a few samples from plants that you know are clean and not sprayed with any chemicals, and see what you think.

The same applies to the leaves. Young leaves are generally better tasting, but I haven’t found much difference in flavor between wild and cultivated plants. Give some a nibble and find what you like best.

How to Identify Wild Violets

Assuming you aren’t plucking your flowers from a specimen you found labeled at a nursery, you’re going to want to be sure you’re looking at the right type of plant.

These plants are all perennials, and most of them go dormant in the summer heat, or at the very least, stop flowering.

Wild violets grow across North America (and the rest of the globe) in moist areas.

For those who live in dry climates, you might find them creeping into your lawn or other areas that are regularly irrigated. For those in wetter climates, you can find them just about anywhere, but especially near streams.

The easiest way to tell if you’ve found a violet is by looking at the flowers. They grow on narrow, leafless stalks, and each one has five petals.

Contrary to the name, they aren’t all purple. Many are yellow, burgundy, or white. The flowers always have three lower petals and two upper petals.

The upper petals are often distinguished from the lower petals by color, and they often lack the veins that appear on the lower portion of the petals.

The two side petals may be bearded, and the lowermost petal is the largest. It often has a yellow center and the heaviest veining. Examine it closely and you’ll usually see a backward-pointing spur that holds the nectar.

Absent the flowers, the leaves form in a basal rosette. The young leaves are curled in on themselves as they emerge, gradually unfurling as they age.

If you look closely, you’ll notice fine teeth along the margins, though some species, like V. lobata and V. sheltonii, have heavily toothed margins.

Most leaves are heart-shaped and come to a sharp point, though some species, like V. douglasii and V. halli, have long, narrow leaves.

If you don’t feel confident identifying these plants by leaf shape, I don’t blame you since they can be so diverse. Instead, wait for the flowers to emerge in the spring. They all look similar, and if you’ve seen Johnny-jump-ups, you know what these flowers look like.

Garlic mustard leaves have a similar heart shape to many violets, so rub the leaves between your fingers. Do they smell garlicky? That’s not a violet!

There are over 100 Viola species found in North America and around 700 worldwide.

In my neck of western North America, we find the yellow Douglas (V. douglasii), stream (V. glabella), Oregon (V. hallii), pine (V. lobata), western roundleaf (V. orbiculata), Astoria (V. praemorsa), goosefoot (V. purpurea), evergreen (V. sempervirens), and fan (V. sheltonii) varieties.

The purple-colored western dog (V. adunca), Great Basin (V. beckwithii), wedge leaf (V. cuneata), Olympic (V. flettii), Howell’s (V. howellii), Alaskan (V. langsdorfii), marsh (V. palustris), and sagebrush (V. trinervata) can be found across western North America.

The white violets in this area include Canadian white (V. canadensis), northern white (V. macloskeyi), pinto (V. ocellata), and western Canadian white (V. rugulosa).

East of the Rockies, you will see purple-flowered Appalachian (V. appalachiensis), common blue (V. communis), triangle-leaved (V. emarginata), Florida (V. floridana), southern woodland (V. hirstutula), Missouri (V. missouriensis), early blue (V. palmata), mountain pansy (V. pedata), arrow-leaved (V. sagittata), northern woodland (V. septentrionalis), woolly blue (V. sororia), and prostrate blue violets (V. walteri).

The eastern yellow species include spearleaf (V. hastata), Nutall’s (V. nuttallii), downy yellow (V. pubescens), and roundleaf yellow (V. rotundifolia).

Some of the most common eastern white species are sweet white (V. blanda), Canadian white (V. canadensis), and sweet white (V. macloskeyi) violets.

Common violet (V. arcuata), field pansy (V. arvensis), sweet violet (V. odorata), and wild pansy (V. tricolor) were brought over from Europe and have naturalized across North America. You’ll find them in lawns, disturbed areas, woodlands, and fields.

Recipes

There are lots of ways to use violets as a garnish. Chop them and sprinkle them on eggs or fish.

Place them whole on salads, sandwiches, souffles, cakes, and ice cream. They’re a delightful addition to Waldorf salad.

Drop a few into an ice cube tray and fill it with water. Freeze, and now you have some elegant ice cubes for your drinks. They go especially well in lemonade.

I steep the leaves and flowers in my homemade kombucha, which you can learn to make at our sister site, Foodal.

Looking for something a little different? You need to try this magical recipe:

Pineapple Soup

This recipe is stolen, stolen, stolen! But it’s so incredibly good that I had to include it here.

All the credit goes to Leona Woodring Smith, who wrote the indispensable book “The Forgotten Art of Flower Cookery.”

I’ve adapted it from the original a bit, but in essence, you’ll combine four cups of pineapple juice with three tablespoons of quick-cooking tapioca, and three tablespoons of sugar.

A bit of lemon peel, three cups of a combination of sliced berries, mangoes, persimmons, or oranges, and, of course, half a cup of violets – and you have a dessert soup that is heavenly.

Top it with whipped or sour cream and tuck in a few violets on the side to create a feast for the eyes.

The Forgotten Art of Flower Cookery

If you’d like the original recipe, along with dozens of other flower-focused recipes, visit Amazon to pick up a copy.

Salad Dressing

The flowers work well in salads, but they also make a killer salad dressing. Why not try both?

You will need to plan ahead for this recipe. Take a packed ounce of fresh flowers and cover them in a quarter-cup of white wine vinegar in a glass jar. Shake and let them steep for 24 hours. Strain.

Stir the vinegar and three quarters of a cup good olive oil together with a teaspoon of Dijon mustard, half a teaspoon of honey (optional), half a teaspoon of salt, and pepper to taste.

Shake or stir together again right before dressing your chosen salad. I love it over arugula and romaine with tomatoes and feta. Top with or toss some flowers into the salad.

Stuffed Mushrooms

Believe it or not, violets and mushrooms work well together.

Heat a teaspoon of finely chopped shallots in butter and cook them on low until soft and translucent. Combine a cup of sour cream with a teaspoon of lemon juice, a teaspoon of white wine, a tablespoon of chopped violets, and the shallots.

Pop the stem out of a dozen large brown mushrooms and soak them in cool water for a few minutes. Drain and dry them by placing them on a towel and allowing them to air dry for a bit.

Place a heaping scoop of the sour cream, using enough to fill in each cap with a rounded mound, and place them on a greased baking tray. Shave a little parmesan on top of each mushroom.

Bake the mushrooms for 10 minutes at 325°F. Sprinkle some more fresh chopped violets on top as a garnish. They’re too pretty to hide.

Infused Water or Tea

Violet water is a vibrantly-hued ingredient that can be used for many recipes, from cocktails and non-alcoholic drinks to icings and sauces.

Grab a glass jar and pack it with violets. Pour boiling water over the flowers so they are just submerged. Cover, shake, and allow it to sit for 24 hours. Strain and use.

To make tea, use two tablespoons of fresh flowers per cup of hot water. Let it steep for five minutes, strain, and enjoy.

Pesto

The mucilaginous nature of the leaves makes for a good pesto. You’ll need:

- 1/2 cup pine or hazelnuts

- 2 cups loosely packed violet leaves

- 1 cup loosely packed basil leaves, whole

- 2 cloves garlic, peeled

- 2 tablespoons lemon juice

- 1/2 cup olive oil

- Salt and pepper

In a food processor, or in a mortar if you’re old-fashioned like me, mix or pound together the nuts, greens, garlic, and lemon juice until a paste forms.

Slowly add the olive oil while continuing to mix until you have a thick, smooth paste. Add salt and pepper to taste. If you’re feeling fancy, top with some fresh flowers.

Greens Soup

I’m assuming you’ve already sampled the leaves and have decided whether they’re for you or not. If you don’t jibe with the texture, you can cut the quantity of leaves in half with spinach.

For this you’ll need:

- 2 medium sweet onions

- 3 cloves garlic

- 4 tablespoons olive oil

- 1 cup chopped violet greens

- 1 cup chopped beet greens

- 4 cups vegetable broth

- 1/2 teaspoon fresh oregano

- 1/2 teaspoon cayenne powder

- 1/2 teaspoon garlic powder

- Salt and pepper

- Shredded mozzarella or parmesan, to taste

Finely chop the onions and garlic and saute in the olive oil in a large stock pot. Add the chopped greens and cook for a minute to wilt them.

Add the broth, herbs, and spices and simmer for 30 minutes. Season with salt and pepper to taste. Dish into bowls and top with a little shredded cheese before serving to taste.

Eat Your Greens… and Purples, and Yellows!

Delicious, nutritious, and beautiful? Some plants are just blessed with more than their fair share of good stuff.

Now I need to know what your favorite recipes are. Share how you intend to use up your floral finds in the comments.

Want to learn more about vivacious Viola plants? We have plenty of guides to help you figure out everything you need to know, including:

[ad_2]

Source link

+ Planting String of Watermelon Succulents

+ Planting String of Watermelon Succulents  with Garden Answer

with Garden Answer