[ad_1]

Gladiolus is a genus of flowering perennials that produce colorful blooms on tall spikes during the summer months.

They grow from corms that readily naturalize in the landscape in Zones 7 to 11. In other regions, these flowers can be cultivated as annuals.

If your gladiolus plants are looking sickly or struggling to bloom, it’s not always because of sub-par cultivation practices – it could mean that disease has struck.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

If illness has come upon your flowers, you’ll probably notice it easily – a diseased gladiolus tends to look very sick.

Whether the symptoms manifest on their blooms, leaves, stems, or bulb-like corms, sickly gladiolus plants won’t be bringing their aesthetic A game to your landscape. And when you’re expecting pretty flowers, a lack of them is pretty disappointing.

That’s why we’ve put this guide together. From symptom spotting to management methods to prevention pointers, you’ll learn everything you need to handle nine common diseases of Gladiolus.

Here are said diseases:

9 Common Gladiolus Diseases

But before we dive in, I should mention that the best way to keep diseases from attacking your gladiolus is to cultivate your plants properly.

By selecting an ideal growing location and dialing in your care practices like watering and fertilization, your specimens will have the health and vigor to withstand many common pathogens.

If you need a refresher about how to grow and care for gladiolus, check out our guide.

And now, let’s discuss some diseases you may need to contend with.

1. Bacterial Leaf Blight

Yes, I know that “bacterial” doesn’t really narrow it down – a bunch of different bacteria can cause blight on leaves.

But in the case of gladiolus plants, leaf blight is caused by species of Xanthomonas, which lie dormant in plant detritus within the soil and can persist for many years.

You should stay alert during periods of excessive rainfall, as that’s when the moisture-loving Xanthomonas bacteria tend to strike.

When the pathogen infects a gladiolus plant, the foliage will develop small, elongated, and water-soaked spots between leaf veins. In time, they turn brown to black, with yellow margins.

The spots look pretty gnarly, and can also interfere with photosynthesis. To prevent infection, well-draining soil is essential, as well as removing any plant detritus that builds up in your planting areas.

Unfortunately, there’s no known treatment for this issue, so you should pull and destroy any symptomatic specimens, and dispose of any diseased-looking corms that you dig up at season’s end.

As the soilborne pathogens are long-lived, don’t replant gladiolus in the area for at least two years.

2. Botrytis Blight

Botrytis blight is caused by fungal species in the Botrytis genus, rather than bacteria.

These pathogens survive in bulbs and in plant residues.

Typically breaking out in cloudy, humid, and moist conditions in temperatures of 50 to 70°F, this disease causes flowers to turn a crinkly brown, leaves to develop tiny brown spots, and stems to develop soft, water-soaked lesions.

The plant tissues eventually decay and develop a coating of fuzzy gray mold.

Below the soil, the corms and roots can rot as well, becoming covered with black, seedlike sclerotia which produce spores that spread the disease. Eventually, infected gladiolus plants will die.

You can slow down disease development by pruning diseased tissues and removing spent flowers as soon as you see them.

Bonide Copper Fungicide

You can also treat your gladiolus with copper fungicide such as this one from Bonide, available at Arbico Organics.

If fungicide treatment doesn’t work, and the gladiolus plants continue to decline, dig them up and dispose of them in the trash, corms and all.

If you have had a problem with botrytis in the past, make sure you look for corms that are noted to have been treated with hot water and/or fungicides.

And ensure you space your gladiolus plants properly, rotate your gladiolus with other kinds of flowers each year, and avoid wetting the flowers and foliage when you water.

3. Curvularia Leaf Spot

Caused by species of Curvularia fungi, Curvularia leaf spot is fun to pronounce, but a total buzzkill to experience.

Spreading primarily via infected corms, the fungus causes leaves to develop white spots that resemble pinpoints, which later turn brown, rounded, and ringed with chlorotic tissue.

Eventually, spots can merge into larger blemishes that blight large areas of the foliage, hindering both aesthetics and photosynthesis.

Since this can be a problem with stored corms, it’s important to store them in the right conditions.

First, you’ll need to cure your corms by keeping them in a storage room kept at 95°F and at 80 percent relative humidity.

Set them in the location to cure for six to eight days, clean them, then cure them for four more days. Afterwards, keep them at 40°F and at 70 to 80 percent relative humidity until it’s replanting time.

Before planting, inspect the corms carefully and if you notice white or brown spots on any of them, dispose of them in the trash.

If you notice symptoms on the gladiolus growing in your garden, it’s best to dig them up and pitch the gladiolus plants as there is no cure.

4. Fusarium Yellows

Also known as Fusarium rot, Fusarium yellows is a nasty condition caused by the fungus Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. gladioli, which resides in infected corms and soil.

Thriving in temperatures of 70°F or warmer, this pathogen causes leaves to wilt, yellow, turn brown, and eventually die.

Flowers, if they develop at all, will be small and deformed, while the corms rot from the inside out and if you dig them up, you’ll see round, sunken brown spots.

If you notice any discolored or lesioned corms before you plant them, then they should be discarded. Same goes for any severely symptomatic plantings in your garden beds.

If you have had problems with this pathogen in the past, do not plant your gladiolus in the same location for at least five years.

5. Scab

Unlike a scab on your skin, this scab isn’t something that you should ignore.

Caused by species of Pseudomonas bacteria that reside in soil and on corms, scab leaves infected corms riddled with brown, round, and sunken lesions with raised edges. In time, they may ooze a nasty bacterial exudate.

The foliage will exhibit small, raised, and reddish-brown dots, which merge in time to form long streaks of necrosis. Eventually, the stem will rot at the soil line, and plants will die.

If you notice any infected leaves, prune them promptly. If infection continues and symptoms worsen, dig up and inspect the corm – dispose of any that show signs of rotting. If you notice that some corms are diseased prior to planting, discard those too.

Soggy soils, warm weather, and excess nitrogen create favorable conditions for the spread of this disease, so provide well-draining soil, monitor for symptoms during warm weather, and be careful when fertilizing nearby plants with nitrogen so that it doesn’t stray into the soil of your gladiolus.

Annual rotation with other flowers is helpful for prevention, as well.

6. Stemphylium Leaf Spot

Another disease that’s a doozy to enunciate, Stemphylium leaf spot is capable of causing some serious damage.

Thanks to species of Stemphylium fungi, this disease causes small, round, and yellow spots surrounding prominent red centers on the leaves.

In time, the foliage will wilt and turn yellow before dying back from the leaf margins inwards, until the entire gladiolus plant eventually dies.

As is often the case when dealing with fungal issues, the pathogen develops in warm, moist conditions, so well-draining soil is essential. Prune infected leaves when you notice them.

Applications of copper fungicide can be effective in the early stages of infection. But as with any diseased plant, it’s best to pitch it once it’s too far gone.

7. Storage Rot

The threat of disease isn’t gone when your corms are put away for the winter. If you store them wrong, they could suffer in storage just as they might in-ground.

Caused by Penicillium gladioli, this type of rot leaves stored corms soft and rotted, with greenish-blue masses of spores often covering the rotted parts. As you can imagine, corms infected with this fungal pathogen don’t yield the best flowers.

When you dig up your corms for the winter, you should only keep ones that are free from blemishes. It’s also essential to cure them properly, as moist conditions promote storage rot.

It doesn’t hurt to check your corms throughout the storage period – if you notice any symptomatic ones, remove and destroy them.

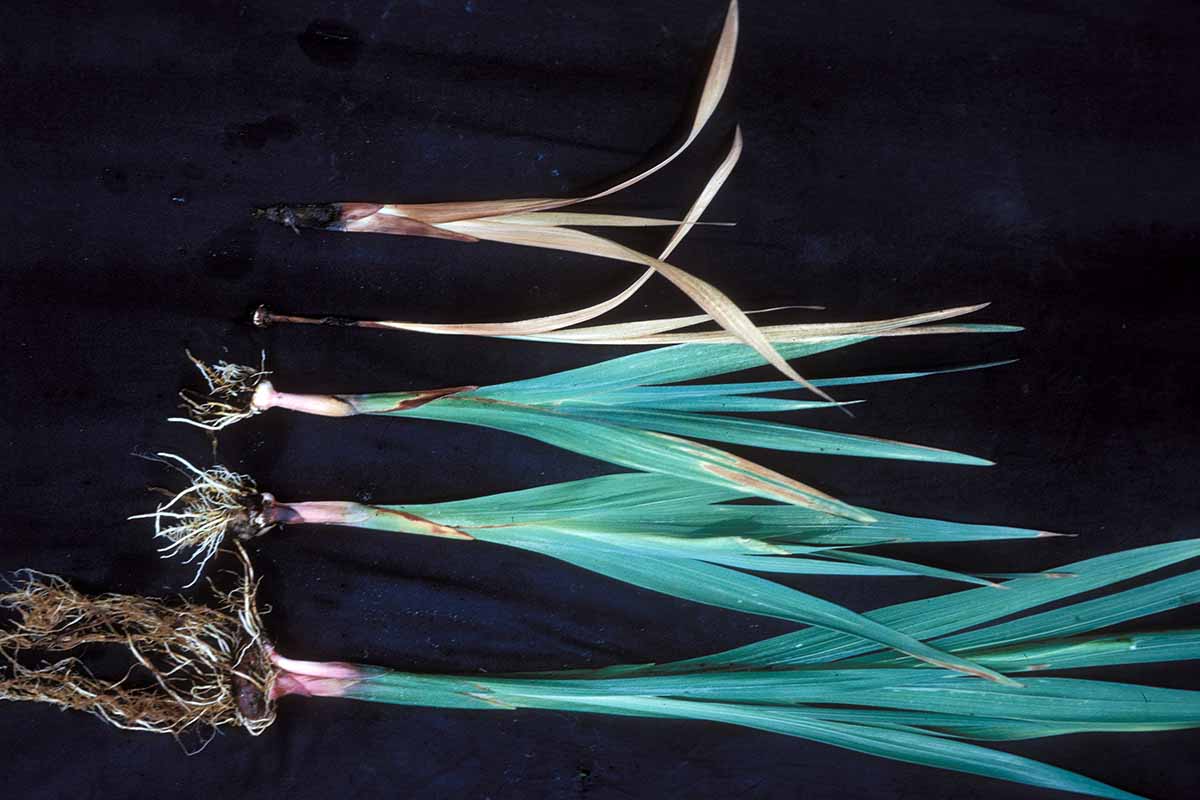

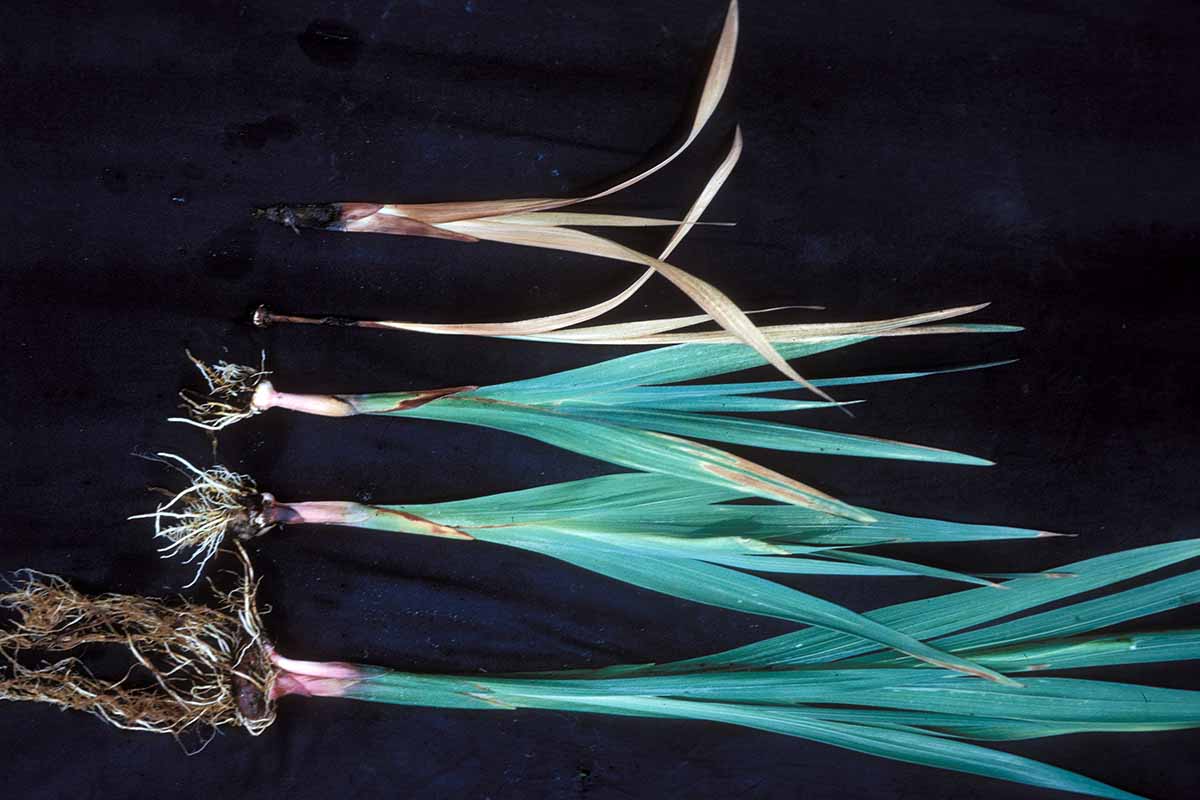

8. Stromatinia Dry Rot

Many rot diseases will leave plant tissues soggy and rotted. With this one, it’s more of a dehydrated and desiccated rot, Egyptian mummy-style.

Stromatinia gladioli is the fungus to blame here, and it can persist in infected soils for long, decade-plus periods of time.

When a corm is infected, it develops small, reddish-brown lesions which sink and turn black in time, often combining to form large patches of dead tissue. Corm husks will turn brown and crispy, while the corm as a whole turns corky and mummified.

Leaf bases turn brown and the foliage can turn yellow and resemble shredded paper. As the infection progresses, foliage drops and the plant dies.

Unfortunately, there’s no known cure once a gladiolus shows symptoms, so you should remove and dispose of any that are infected right away. Copper fungicide can help protect specimens that are not showing signs of infection.

After you have disposed of infected gladiolus plants, you can solarize the soil to kill any remaining pathogens and ensure the site is safe for future plantings.

9. Viruses

There are a number of different viruses that infect gladiolus plants, including mosaic and ringspot viruses.

Symptoms of viral infection include mottled leaves, ring-shaped leaf blotches, and gnarly-looking foliar streaks, which usually result in reduced aesthetics and plant death.

The viruses are usually spread by infected tools, feeding insect vectors, or both.

Since plant viruses are incurable, it’s best to destroy any gladiolus that show signs of infection to prevent transmission to nearby specimens.

Keeping on top of weeds and pests, and keeping your garden tools sterilized can help to keep viruses at bay.

It’s a Thrill When Your Plants Aren’t Ill

It may be obvious to say, but gladiolus plants look a trillion times better when they’re not sick.

Plus, it’s kind of a rush when the growing season arrives and you don’t have any sick plants to deal with.

And even if you do, at least you know how to manage them and prevent their spread in the future. Because that’s the difference between good and great gardeners: the ability to take problems and deal with them in stride.

Have you had problems with your gladiolus? What was the problem? Let us know in the comments section below, and if you’re struggling, feel free to submit a picture so we can help you out!

And for more information about growing gladiolus in your garden, check out these guides next:

[ad_2]

Source link

+ Planting String of Watermelon Succulents

+ Planting String of Watermelon Succulents  with Garden Answer

with Garden Answer