[ad_1]

The latest edition of “Architizer: The World’s Best Architecture” — a stunning, hardbound book celebrating the most inspiring contemporary architecture from around the globe — is now available. Order your copy today.

Completed in 1933, the Paimio Sanatorium is one of Alvar Aalto’s crowning glories. The Finnish master planner entered a competition to design a cutting-edge healthcare facility four years before it opened, responding to an urgent need.

At that time, pulmonary TB was killing around 10,000 Finns each year, and the numbers carrying the disease were much higher. Today, the ‘White Death’ has disappeared from the country, and Aalto’s iconic healthcare facility is a UNESCO World Heritage Site set among stunning pine forests, around one hour’s drive from Turku.

The city is currently undergoing an architectural overhaul of its own, focused on the cultural sector. One of Aalto’s lesser-known gems is found there — the headquarters of Turun Sanomat, Southwest Finland’s biggest regional newspaper. Paimio is around a 30-minute drive from the office, and around 40,000 architecture and design fans flock here each day to see a groundbreaking example of pre-war functionalism, unique in its combination of technical innovation and the healing power of nature.

This concept greets visitors before they reach the front door, surrounded by awnings that share more in common with a seaside gelateria than a hospital entrance. Your approach is flanked by green spaces beyond those woodlands and even further rural Finland. A masterpiece of Scandinavian Modern—minimalistic, purposeful, yet respectful of nature and ergonomics — once inside, the facility is filled with fascinating artifacts.

Image courtesy of Alvar Aalto Foundation

Paimio Armchair 41 and 42 could be the most iconic. Archetypes of Finnish and Scandinavian design, dimensions and form were dictated by one goal — achieving the best possible position for breathing. This applies even in the Dining Hall, where posture is more formal but respiration remained a critical factor in how seating looked.

In the former Reading Room upstairs, windows can be pulled down to near-45-degree angles, keeping the atmosphere well-circulated. Stairwells aside, from almost every direction natural light floods the interiors, while artificial sources were never centered in rooms and on ceilings in a bid to avoid any uncomfortable glare. Meanwhile, vibrant colors — blues, oranges, yellows, mint greens — were chosen for mental health benefits, the idea being to keep the place cheery and also bring as many tones from nature inside.

Door handles were given enough thought to ensure sleeves would not catch when people tried opening them without touching surfaces with their bare hands. Sleeping two-to-a-room, once unpacked patients would find silent washbasins, so nobody would be disturbed unnecessarily in the night.

Triangular lampshades minimized dust and particles. Other light were covered by glass shades, skirting boards replaced by flooring curving up to meet the window frame. Cupboards suspended off the ground. Cleaning prioritized at every turn.

Image courtesy of Alvar Aalto Foundation

These last points really set the scene — design informed by the specifics of everyday life inside a sanatorium. An experience which would have been terrifying yet relentlessly monotonous for the most part. Those who went through it seem to have left in indelible mark on the atmosphere here.

Our guide, Heidi Lehto, paints a vivid picture of what some may have been like. We hear about the huge cast iron oven, never used for cooking but allegedly a stash spot for contraband booze. You can almost picture patients in this environment, those who had enough strength walking the corridors, other being wheeled. Like a sepia-hued mental image of One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, only with a respiratory disease.

Like McMurphy’s hospital, no alcohol, drugs, cigarettes, sex or romance was permitted here. Yet love blossomed amid the sputum, drinks were drunk, and at least one Chief Physicians smoked 75-a-day. Taking more than one for the team, as it were.

Lifelong friendships were formed, although for some were shorter than others. One-third would never be discharged and pass away inside these walls. Others would spend months or even years here, which is why Aalto focused on creating a sustainable hospital in the human sense. A place you could live, not just be treated.

Image courtesy of Alvar Aalto Foundation

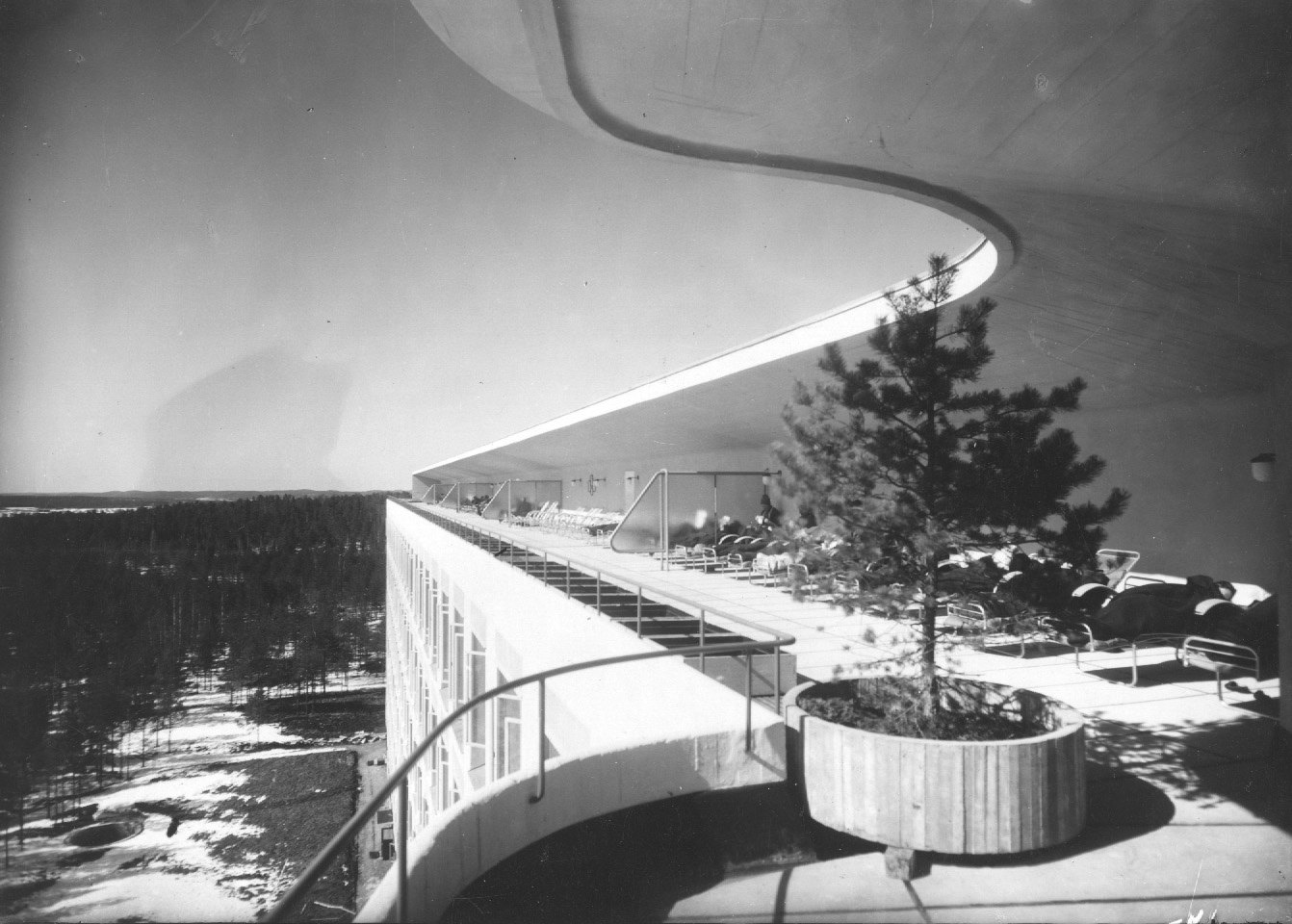

All sanatoriums insisted on patients spending much of their day in the fresh air. The theory was this would clean out the lungs. At Paimio, the deal was five hours outside. And this was the case until temperatures dropped below -15C on the seventh floor balcony, which could accommodate 120 stretchers.

The terrace offers impressive vistas across the boreal treetops, and is a striking example of the strange atmospheric juxtaposition pervading the complex. Aalto opted for curved concrete, attempting to reflect the surrounding topography and lines found in nature more generally. And it’s this type of detail that defines his Paimio Sanatorium. Here, for many that sat here in past, this would be as close as they’d get to a green space again. A viewpoint from which you can smell the dew and hear bird calls on the breeze. Then maybe a cough. Or that could just be the ghosts.

The latest edition of “Architizer: The World’s Best Architecture” — a stunning, hardbound book celebrating the most inspiring contemporary architecture from around the globe — is now available. Order your copy today.

[ad_2]

Source link