Phytomyza gymnostoma

In December 2015, bucolic Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, was the location of the first confirmed infestation of the invasive allium leaf miner in the US.

Since then, this intruder has continued its inexorable march throughout Pennsylvania to Maryland, New Jersey, New York State, Massachusetts, and as of early 2020, Connecticut.

As its name suggests, this pernicious pest attacks high-value commercial crops like onions, garlic, leeks, chives, and shallots, as well as wild and ornamental Allium species.

It can totally destroy an allium crop and cause tremendous losses for commercial and home growers alike.

The allium aka onion leaf miner is a particular threat to organic and home gardeners, since they do not routinely treat their crops with synthetic insecticides.

Growers are highly concerned that this pest may migrate to the western US where onions are a major commercial crop.

As Cornell entomology professor Brian Nault told the Cornell Chronicle, “this has been a huge concern” for onion growers.

In this article, we will cover the biology and identification of these pests and the control measures that you can use to fight back against an infestation:

What Are Leaf Miners?

The allium leaf miner (ALM), Phytomyza gymnostoma, is a true fly in the Agromyzidae family.

Native to Poland, this little fly had spread to 21 countries in Europe and two in Asia before it reached the US.

The US already has two native leaf miners from the same insect family that can infest allium species. They include the American serpentine leaf miner, Liriomyza trifolii, and the vegetable leaf miner, L. sativae.

These native species are much less of a threat to allium crops as they cause very little damage.

This is in part because the Liriomyza species are native to the US and are likely to have evolved with a raft of natural enemies that help to keep their populations in check.

Typically, invasive insects from other parts of the world pose a much greater threat to crops, because they have no natural enemies in their new area.

In addition to the ALM, there is another invasive leaf miner – that also attacks alliums – spreading throughout the northeast US.

The larvae of the leek moth, Acrolepiopsis assectella are caterpillars that are visible on the leaf surface. These insects are members of the Acrolepiidae family and can easily be distinguished from ALMs.

The term “leaf miner” refers to the damage that the insects cause on plants rather than to their taxonomic classification.

The larvae of many types of flies, butterflies, moths, and bees can live inside plant leaves where they feed as they mature.

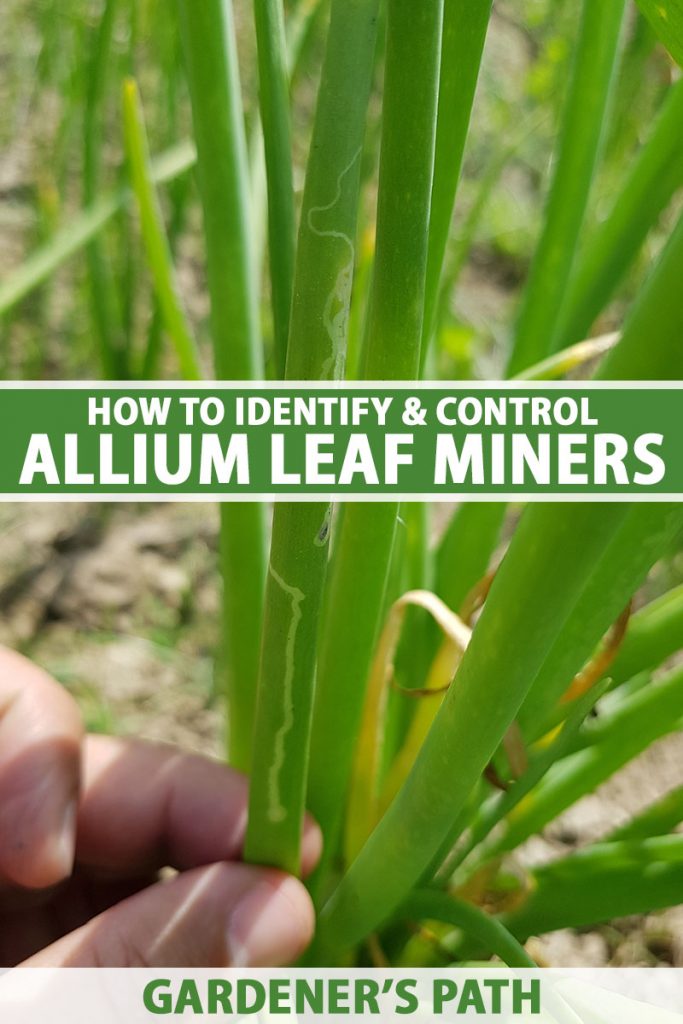

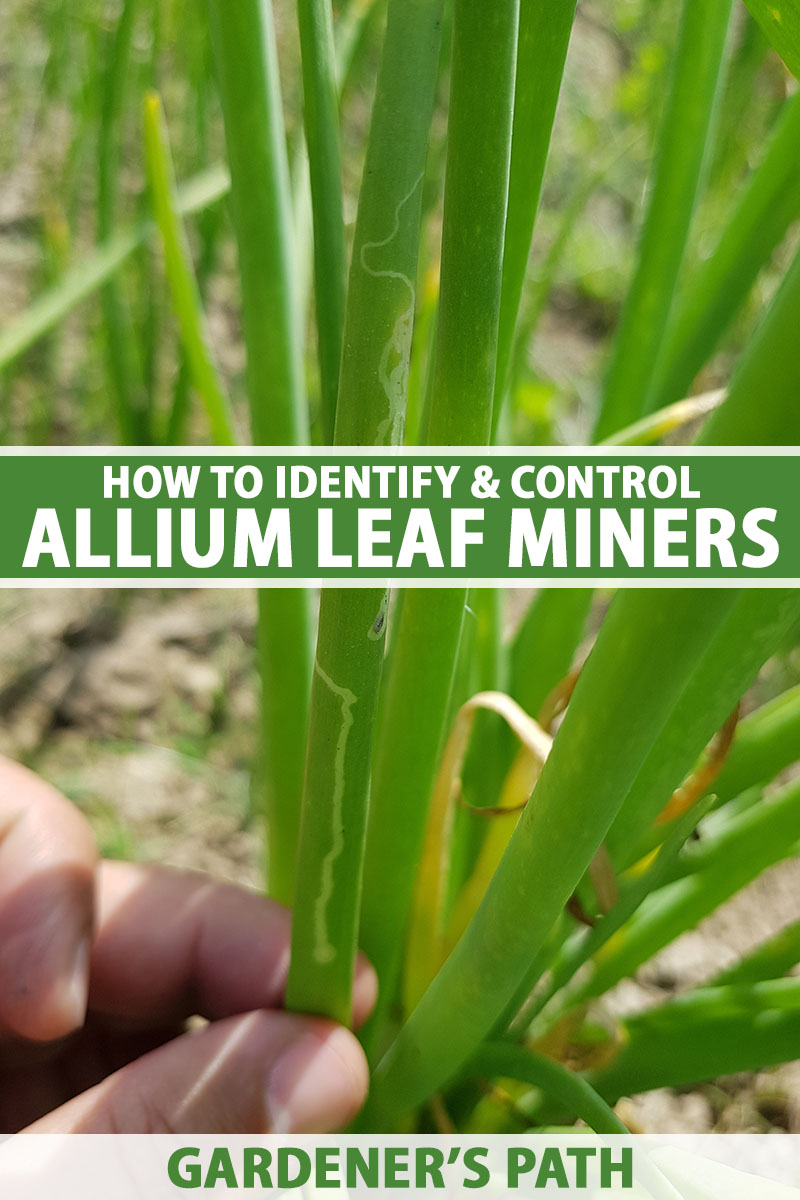

They bore into the bulbs, stems, and foliage and the damage they cause manifests as tunnels that look like erratic lines on the leaves as they travel to feed. Different types of leaf miners can cause varying patterns.

In addition to the direct damage they cause, these feeding tunnels can be colonized by fungi or bacteria, such as those that cause soft rot. These secondary infections can cause the plants to rot and die off.

Identification

The adult ALMs are diminutive flies of about an eighth of an inch long.

They are gray or black, and can be identified by the distinctive orange or yellow patch on the fronts and tops of their heads. The flies are black behind their eyes.

The sides of their abdomens and “knees” are also yellow.

If you look closely, you can see dots under their clear wings, which sit horizontally over their abdomen when the flies are at rest.

The tiny eggs are white and slightly curved. They are difficult to see with the naked eye.

The headless larvae, or maggots, can be yellowish, cream, or white, and are up to a third of an inch long.

The pupae are a critical stage for identification, since the flies can pupate inside the stem tissues but remain visible to the naked eye. The oblong pupae are about 0.15 of an inch long and reddish to dark brown.

It can be difficult to differentiate the adults of allium leaf miners from other species of fly, as they are so tiny. Experts tell them apart by dissecting them under a microscope.

Biology and Life Cycle

ALMs have two generations a year. The first emerges in the spring from pupae that have overwintered in the stems, bulbs, or soil.

After the eggs have hatched and the larvae have tunneled through your precious alliums, eating their fill, they pupate and start the cycle again.

The adult flies feed on the sap of allium leaves. Before she lays her eggs, a female fly will make holes in the foliage using her ovipositor – the long tube that is used to deposit eggs.

She will make a large number of punctures, which look like a series of small white spots in a linear pattern on the top of the leaf surface.

Both male and female flies feed on the sap that exudes from these damaged areas, and the females will return to lay eggs in the puncture marks.

The females lay their eggs approximately a week after making the punctures. The egg masses on the leaves look like a row of brown dots.

The adult flies that emerge in the spring typically lay their eggs over the course of four to five weeks.

After the eggs hatch, the larvae tunnel through the leaves, eating their fill as they make their way towards the stem.

It’s this feeding that produces the characteristic trails of a leaf miner. These trails widen the closer they get to the stem, as the size of the maggots increases.

The mining and feeding causes the plant tissue to soften, increasing the susceptibility to bacterial and fungal infections.

When they have reached the base of the leaf or the bulb, the larvae pupate – there can be up to 100 pupae on each plant.

You can typically see the pupae at the base of the plant or on the surface of the soil nearby until the fall.

Then, the next generation of adults emerge from September through November and lay eggs for five to seven weeks.

The pupae formed from this generation overwinter until the spring of the following year and emerge from March through May.

Organic Control

Dr. Gladis Zinati, Director of the Rodale Institute’s Vegetable Systems Trial, and colleagues, conducted two-year trials to determine which methods can be used to control the ALM.

They found that combining multiple integrated pest management (IPM) tools can reduce crop losses from these pests.

As they are a relatively new arrival on US shores, research is still ongoing to determine the best way to deal with them.

Most of the research is typically focused on commercial growers rather than home gardeners, but we can pick up some tips from what the pros do to avoid crop loss.

To begin with, you need to establish that you are actually dealing with the allium leaf miner and not some other type of insect.

Monitor the Populations

As it is the larvae that cause the most damage, it makes sense to take steps to protect your crops during the time that the females are most likely to be laying eggs.

But how would you know that they’re around?

Sticky traps are often used to identify the presence of pests, and these can be deployed in your garden to monitor what insects are hanging around your veggie patch.

Dr. Zinati’s team found them to be a useful tool as described in a 2020 article in the Pennsylvania newspaper Lancaster Farming where she mentions that the use of yellow sticky traps is far more effective than using blue ones.

The traps should be placed in late winter or early spring and checked regularly to identify which pests are visiting your garden. You can keep them in place throughout the growing season, or replace in late summer to monitor the presence of the second generation.

Other ways to monitor the presence of these insects include looking for the marks produced from oviposition on the leaves. These are typically the first indication that your plants have been infested.

You should also look for leaves that are curly, wavy, and distorted – although this typically happens later in the season, after the larvae have had a chance to do extensive damage. The other leaf miners that attack alliums do not cause this symptom.

Later in the growing season, you can pull plants that are exhibiting symptoms out of the ground and pull the leaves back to check for pupae.

If you think that you may have an infestation of ALMs, you may send in your sticky traps to your local extension agent for a professional diagnosis.

Floating Row Covers or Insect Netting

If you are growing your allium crops in a particular location for the first time, you can use floating row covers or insect netting to protect your crops from these insects.

It is critical to place them over your plants before the adult flies are active, either in the spring or early fall.

You’ll need to leave them in place for at least four to six weeks to prevent the flies from laying eggs in the foliage.

It’s a good idea to place sticky traps inside the row covers to check that none of the pests are finding a way in.

Unfortunately, floating row covers will not work on areas of your garden that were previously planted with alliums, since the insects can pupate in the soil. Then, the adult insects would be trapped inside with your crop!

Sources of the insects also include the wild onion grass that could be growing in your garden.

If you see more than one or two plants with ALM damage, it is probably too late into the flight season to be able to use row covers.

Plastic Mulch

Dr. Zinati and colleagues compared onions grown with differently colored plastic mulch compared with bare ground to see what effects it had on the levels of infestation.

They found that there was very little damage from the leaf miners when black or reflective silver plastic mulches were used. Red plastic did not work as well.

Unpublished research by Cornell University entomologists Grundberg and Rusinek, which was presented to the Eastern New York Commercial Horticultural Program in January 2021, showed that silver reflective mulches are 30-35 percent more effective at controlling ALM than black or white mulches.

However, even with this degree of control, the pests can still infest the crops.

All is not lost, however!

Plastic mulches work well when combined with other techniques, such as the use of Spinosad, as part of an IPM program.

Spinosad

Spinosad is an organic insecticide derived from the fermentation of certain bacteria.

Drs. Nault and Fleischer found that applying this product to the roots of transplant onions, scallions, and leeks or to the soil in plug trays for plant starts reduced the amount of damage by 90 percent after transplantation.

Grundberg and Rusinek concluded that the combination of a reflective mulch with two applications of spinosad combined with the horticultural soap M-Pede, available on Amazon, can reduce the damage to acceptable levels so that the alliums could be sold commercially.

M-Pede Insecticidal Concentrate

The combination of these two techniques was by far the most effective organic control method for the flies.

For the home gardener, spraying your plants with Spinosad at the first sign of infestation can limit the damage sufficiently to allow for a successful harvest.

Monterey Garden Insect Spray

You can buy OMRI-certified Spinosad in the form of Monterey Garden Insect Spray, available from Arbico Organics.

Spray both the upper and lower surfaces of the leaves. If you see continued damage, repeat the application. You can do this two or three times throughout the season as needed.

Do not apply more than five times a year.

Cover Cropping

Dr. Zinati found that growing a mixture of tillage radish, mustards, and rapeseed as a cover crop before growing yellow onions significantly reduced the numbers of ALMs.

Several factors appear to be involved.

One is that these plants from the Brassica genus added sulfur to the soil, which was absorbed by the onions and increased their pungency. The leaf miners appeared to target onions that were less pungent.

The yields in onions that followed this cover crop were twice as large as those that followed a cover crop mix of white Dutch clover, sunflower, rye, and hairy vetch.

The reason for this was that the non-brassica cover crop had more than double the numbers of mycorrhizal fungi, which increased the amount of nitrogen available to the crops, which increased their appeal to the leaf miners.

And excitingly, onions have a better storage life when there is more sulfur in the soil.

Cultural Methods

One strategy can be to wait to plant your crop until after the ALMs have finished laying eggs. This timing will vary based on your location.

Avoid fertilizing with nitrogen excessively, since that can increase the degree of leaf miner infestation.

Keep your plants well irrigated to reduce their levels of stress. This will allow them to fend off secondary infections that can lay waste to your entire crop.

Rotating your crops is always good gardening practice, and home gardeners have more opportunity to do this than large commercial growers.

Practicing good sanitation at the end of the growing season is critical for controlling these flies the next season. It is important to rid your garden of ALM larvae and pupae. Remove all plant debris and dispose of it in the trash, not on your compost pile.

To be absolutely sure that you have removed all larvae and pupae, your best bet is to burn the infested tissue – if that’s permitted in your locale – or bury it as deep as possible and solarize the soil by placing clear plastic over it.

Biological Control

Unfortunately, the common strategy of applying beneficial nematodes to the soil does not work in the case of leaf miners.

However, the parasitic wasp Diglyphus isaea lays its eggs on the larvae of all leaf miners in the Agromyzid family and kills them.

Technically, these types of wasps are known as parasitoids.

This type of treatment works best if the wasps are released early in the season before the adult ALM populations build up.

Diglyphus isaea Parasitic Wasps

These parasitoids can dramatically lower the populations of leaf miners, but they will not provide total control. They should be used as part of an IPM strategy.

You can buy these wasps from Arbico Organics.

Introduce the wasps on two separate occasions, a week apart, and repeat in time for the second generation in fall. twice

If it is hot and sunny, it’s recommended to release the wasps early in the day or in the late afternoon or early evening.

Chemical Pesticide Control

As described in the journal Economic Entomology, Dr. Nault’s research team tested various control measures on onions, scallions, and leeks in New York State and Pennsylvania.

Chemical insecticides were found to be highly effective at eradicating ALMs and reducing their damage.

Effective synthetic insecticides available to homeowners include abamectin, imidacloprid, and cyfluthrin.

Abamectin Insecticide

You can find abamectin available from Amazon.

Apply to the foliage when you first notice the leaf miners. Wait seven days and then reapply.

After two applications, you should rotate to a different type of insecticide.

Wait 30 days after application before harvesting your onions, garlic, or other types of allium.

And always remember to take adequate precautions when you use chemicals in your garden and always follow the manufacturer’s directions.

The Threat Is Real

Allium leaf miners are pests that are highly destructive to high-value crops like onions, scallions, chives, garlic, and leeks.

These insects are entrenched in the mid-Atlantic area and have spread north to Massachusetts and Connecticut.

Even if you do not live in these locales, you should be aware of the possible spread of this insect into your area and take precautions to protect your crop.

Have you battled allium leaf miners? Let us know how your crop fared, and share your tips in the comments section below!

And for more information about growing alliums in your garden, check out these guides next:

© Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Product photos via Abamectin, Arbico Organics, Gowan, and Monterey. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock. With additional writing and editing by Clare Groom.

About Helga George, PhD

One of Helga George’s greatest childhood joys was reading about rare and greenhouse plants that would not grow in Delaware. Now that she lives near Santa Barbara, California, she is delighted that many of these grow right outside! Fascinated by the childhood discovery that plants make chemicals to defend themselves, Helga embarked on further academic study and obtained two degrees, studying plant diseases as a plant pathology major. She holds a BS in agriculture from Cornell University, and an MS from the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Helga then returned to Cornell to obtain a PhD, studying one of the model systems of plant defense. She transitioned to full-time writing in 2009.