The importance of keeping a conversation flowing is not only the stuff of successful dinner parties, it forms the very basis of our continually developing societies and ideals, through the testing and re-testing of what we believe. What we say and what we listen to reflect back to us who we are, and provide an ever-evolving snapshot of ourselves as a community, as a wider society and as a nation.

Remembering that the concept of nationhood is both identity-empowering and dangerous, the importance of conversation is made starkly clear in this age of online misinformation. All sides of any discussion – architectural or not – need constant airing, and across many platforms, to avoid the silo effect.

In any conversation, it is fascinating to observe who is doing the talking (how are they related to the dominant narrative and do they leave room for others to speak?) and it is exciting to observe the subtle shifts of power that can occur. Hopefully, we can learn tolerance for opinions that are not our own – and, perhaps, even change the conversation, and who is doing the talking, completely.

When Chris Barton started in his role as editor of Architecture NZ, he chose to celebrate conversation in architecture and, as part of his plan, invited me and the wonderfully poetic Pip Cheshire to share our opinions in each issue. The inclusion of opinion in the magazine is a brave move; in New Zealand, we have a small architectural community and a cultural tendency to keep our heads below the parapet – possibly thanks to our strong collegial bonds and a perceived risk of offending someone we hold in high regard.

Barton’s 2018 invitation was daunting yet exciting and this issue marks a full two years since I took up the challenge. In that time, I have had complete freedom to write on my passions – drawing, education, history and equity. I hope that, in that time, many conversations have been stirred up and, judging from the breadth of viewpoints as described in the feedback below, there will have perhaps been an argument or two.

Sharing my opinions has been an incredible privilege and I am honoured to have been trusted with such a powerful platform. It is now time for me to pass this privilege to someone else and to make room for a new voice in these pages.

Most importantly, I want to say a huge and warm thank-you to Chris Barton, Amanda Harkness and Nathan Inkpen at AGM, who have supported the column completely, and to my fellow ‘opinionist’ Pip Cheshire, whose own musings have set the bar impossibly high.

For me, architectural conversations are important because, quite simply, there is so much to think about and, therefore, talk about. The complexity of issues to juggle in the making of beautifully crafted buildings extends across many fields, from technics to aesthetics, semantics, economics, sociology and more. Talking through these complexities keeps ideas alive, tests opinions and keeps architecture as a discipline pliable.

Some aspects that I wish were on the table more often for discussion include the skills that architects have in social observation and human behaviour. Despite their presence in every brief, the socio-economic, cultural or political influences of a project often remain undeclared. Architecture, very clearly, has a social programme – it always expresses existing authority structures (look at the development of the bank as a building typology) and controls or reflects the rituals of our daily lives.

By continually reviewing our pre-conceived ideas or assumptions through constant conversation, these social and ritualised observations can be included by the architectural team into the project. The project itself becomes an expression of that conversation, which possibly influences subsequent design.

Feedback to the opinion columns has been rare but welcomed. Not long before the deadline submission for this column, two contrasting views were received on the very same day. Edward Persimmon (a nom de plume, presumably because there is so much to hide) wrote an email addressed to the editor. After firstly denying climate change (“totally unproven”) and rallying against the Labour party, he declared that “Lynda Simmons goes the full Marxist monty in her ‘Parallel Education Systems’ piece…”. Despite being off topic, he somehow managed to include his opinion on “the whole false premise of the Black Lives Matter movement”, before completing the sentence by calling me a racist. The second piece of feedback that day came as a text, from architect Jane Waldegrave, saying: “I just wanted to say many thanks for your article in Architecture NZ – Parallel Education Systems – what you say is so important and very well said”. The difference between the two was stark and pleasing, and it is an indication that our printed conversations have been happily reaching a broad range of people.

Since the first issue of 2019, no less than three columns have been dedicated to the call for a radical shift in practice management, noting that traditional structures do not reflect or support the contemporary architectural workforce. (Those architectural practices that have been sluggish in addressing issues of equity have since discovered, through the forced COVID-19 lockdown experiment, that flexible and reduced-hour working weeks are successful indeed. The usual ‘not dedicated’ or ‘not-workable’ myths have been destroyed and more people than was expected have elected to remain in flexible structures.)

Another column addressed equity in terms of the effect of financial structures on architecture, inspired by the talk given at the NZIA 2019 in:situ conference by OMA’s Reinier de Graaf, and his concern at the immoral position that architects play in those systems. (Equity has shaped much of my life – I was that annoying kid in the playground who challenged the rules of a game if they weren’t fair, even if it was at my own expense.)

My passion for history and its shaping has revealed itself in various forms, from the importance of publication and awards, to the threatened print environment in which we now find ourselves, and reflecting on the loss of the Architecture Library at the University of Auckland. I joined

the climate emergencies discussion in one column, and two more were dedicated to education, both celebrating the value of variety in educational approaches. A further column considered the role of drawing in the design studio, which is my own educational and teaching focus.

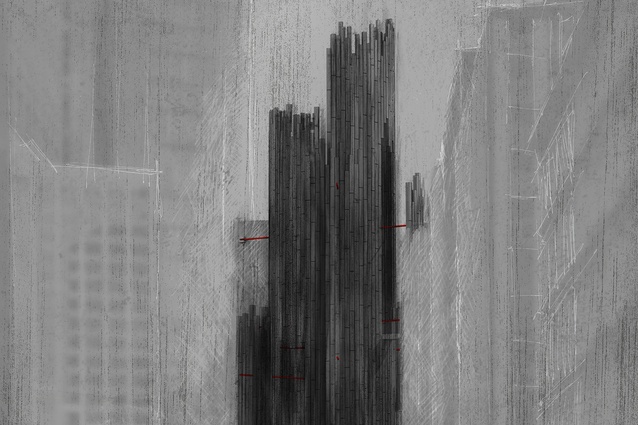

But my greatest pleasure of all has been through the opportunity to publish a single image with each opinion column. I determined to celebrate drawings produced by students, as a way to give visibility through publication to some of the extraordinary work that is produced in the universities. The selected images have been drawn (mainly) from student thesis projects that I have had the privilege of supervising and, in some cases, from student work of earlier decades. Each illustration has allowed my own love for drawing, and its importance in architectural education, to be reflected alongside my words.

Thanks for listening; I feel honoured to have had your attention.

[Editor’s note: Chris Barton, editor of Architecture NZ noted, “In this January/February 2021 issue of Architecture NZ, we farewell columnist Lynda Simmons. Her talent for deploying solid research to get to the nub of issues facing our profession will be greatly missed. Many thanks Lynda for your brilliant and insightful perceptions over these last two years.”]

Read more from Lynda’s column here.

More on top image: Wang’s thesis research explored connections between animate and inanimate materials, and whether or not architecture may be reconsidered as a living being. Using concepts of ‘life-force’ from Japanese Shinto and Māori whakapapa belief systems, a series of urban structures explores architectural options for ‘a city of invisible spirit’. Wang opens a conversation about relational thinking in an urban context.

The thesis programme at the University of Auckland School of Architecture and Planning is a full-year design-by-research project. Each student selects their own field of study and sets their own brief.